News feed

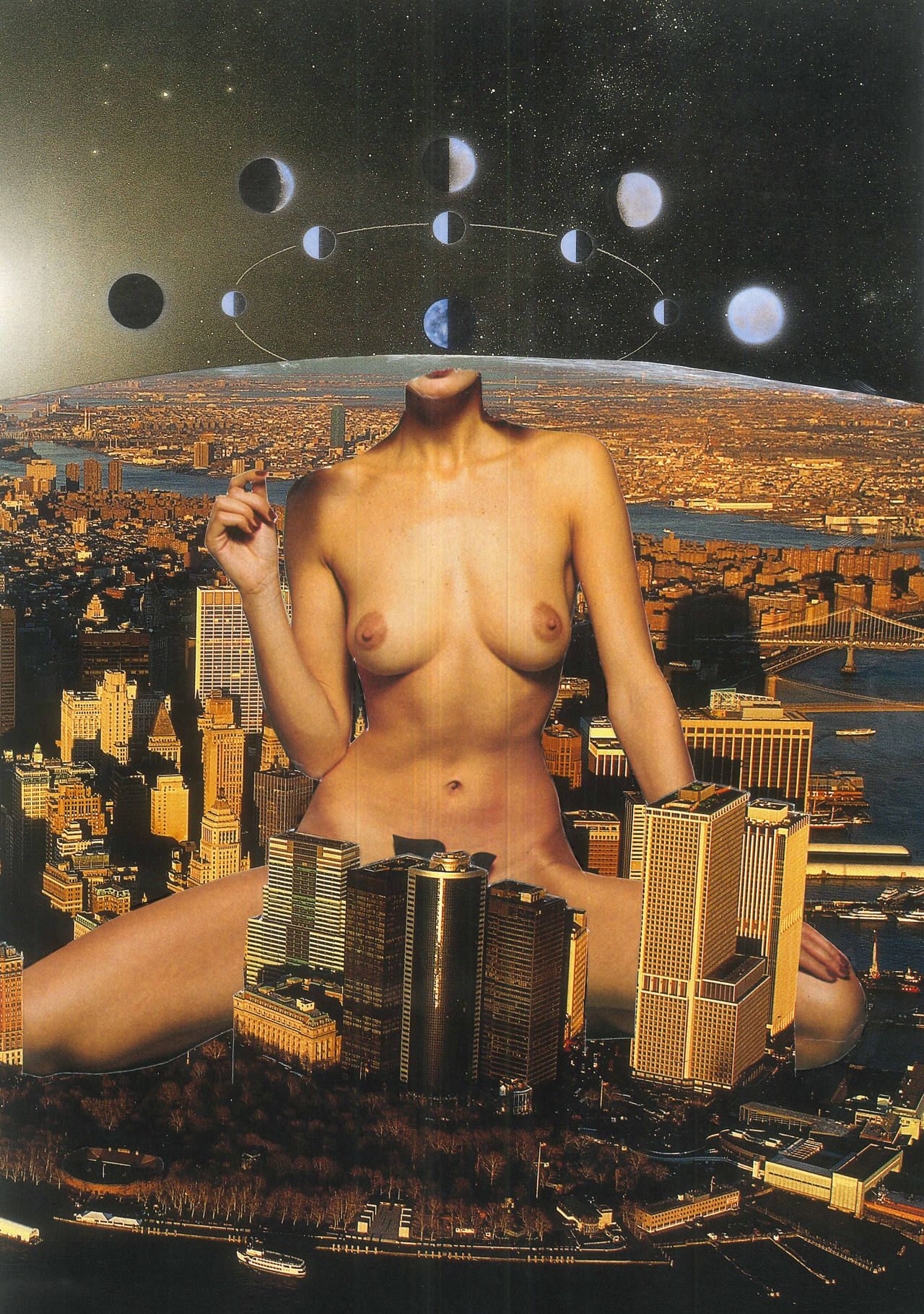

“I don’t want women to be sex objects or any of that,” wrote critic Suzy Menkes about Gianni Versace’s dominatrix-saturated Fall/Winter 1992 show. Aptly titled ‘Miss S&M’, the collection was groundbreaking in its overt sexuality, and though it received mixed reviews at the time, it lives on as an important turning point in fashion history. A few years later, Tom Ford took Gucci, a once flailing brand teetering on the edge of obscurity, and catapulted it to newfound success with the creative director’s sultry spin on luxury clothing. This reinvention saw Gucci become synonymous with an insurgent feminine sensuality and generated growth of over AUD $2.1 billion for the Italian fashion house. Since then, the demand for figure-hugging silhouettes, peek-a-boo cut-outs and sheer fabrications have seduced their way into every woman’s wardrobe. But in 2023, it takes much more to excite than a bit of skin.

After an extended reign of hommes girl power dressing and ‘Grandmillennial’ cottagecore, it’s become clear in recent seasons that sex is back on the menu – and more X-rated than ever. Gone are the days when a knee-skimming hemline could cause a car crash or when a flash of leather or lace could incite panic. Instead, Julia Fox wears nothing but her underwear to pick up groceries, Kim Kardashian casually sports a leather Zentai gimp mask all around Paris with glee (or at least we think – it was hard to tell), and a tower of 200,000 condoms finds a home as the backdrop to Diesel’s Fall/Winter 2023 show.

From the runway to red carpets, a new kind of uninhibited sexuality is being served up in abundance, with ‘stripper’ platforms, bondage-like silhouettes, fishnets, latex, exposed thongs, and teeny tiny hemlines commandeering the trend cycle. From burgeoning brands like Nensi Dojaka, GCDS, Jacquemus, Heaven by Marc Jacobs and Namilia to heritage brands that have long pushed the envelope like Alaïa, Mugler and Alexander McQueen, everyone’s getting in on this new era of sexed-up fashion.

Beyond the clothing, the movement has also given way to a new guard of muses. Since starring in the second season of HBO’s Euphoria, Chloe Cherry has gone from a pornstar with 200 films under her studded leather belt to fashion’s latest muse, fronting the Spring/Summer 2022 Versace campaign with her Bratz Doll lips and stunned doe eyes. Elsewhere, designer and actress Jessie Andrews has quietly become one of the most in-demand “It” girls of the past few years – and she also just so happens to have gotten her start in adult entertainment. Julia Fox leans into her former dominatrix work, often tapping into the same aesthetics with her personal style. Mia Khalifa is taking the fashion world by storm and openly talking about her experience in the porn industry, and then, of course, the WAP queen herself, Cardi B, who, as a former stripper, has been candid about her past life.

In many ways, this sex-positive moment in fashion is one to be celebrated. No longer is ‘sexy’ defined by the male gaze, and welcoming a historically marginalised community to a seat at the Cool Kids table means lifting the velvet rope of an industry steeped in elitism and embracing a different perspective. But as Dr Dawwn Karen, author and the godmother of fashion psychology, warns, this might not be the sexual liberation it’s being sold as.

“Mainstream media has a habit of selling us the idea of progress for women, but there isn’t always substance below the surface,” she tells GRAZIA.

“We see it all the time with performative activism – brands just trying to ride the coattails of a cause as a way to virtue signal or earn some cool points.”

Female pleasure and our sexual agency may appear to be a focus of the zeitgeist, but much is left to be questioned about genuine progress when we zoom out. In a year where we’ve witnessed the U.S. Supreme Court overturn the constitutional right to an abortion and the Human Rights Watch declare that it will take another 286 years to close the global gender gaps, reconciling the precarious state of progress for women with the current trending fashions is an unnerving contradiction. Are we really moving the dial forward for us, or is sex positivity serving as a lucrative commercial opportunity for brands just wanting to cash in on a bit of cultural currency? And when we look at where we’re borrowing these aesthetics from, the question becomes even more murky.

As with anything that has associations with a socio-cultural group, the line between embracing something for its benefit and tokenising it for ours is becoming increasingly blurred. On the one hand, normalising these niche trends to the masses can help to dismantle centuries of denigration towards sex workers and enable generations of people to tap into their own bodily autonomy. On the other, we risk glossing over the very real struggles that sex workers face, dressing up in their professional garb as a bit of fun costumery that we have the privilege of taking off without the tribulations and stigmas a life in sex work can come with.

For some perspective, there’s a 45-75 percent chance sex workers will experience violence throughout their careers, according to the Gender Policy Report – and that doesn’t include violence from law enforcement or the plight of incarceration. As sex therapist and former sex worker Raquel Savage argues, the inequity of who gets to seize this sex appeal calls for a reality check.

“Everywhere you look, hoe aesthetics are being appropriated and incorporated into declarations of liberation,” Savage writes in an essay for Bitch. “Part of feeling liberated as a woman absolutely can (and does) include moving away from purity politics, (re)learning how to set (monetary) boundaries and expectations of our partners, and understanding that autonomy means, ‘I own my body, not you’.

“But it becomes clear that praxis is only allotted to certain people; that dabbling in sexual liberation is for folks who aren’t actually hoes, don’t actually sell nudes online and don’t actually sell pussy.”

Dr Karen, who was introduced to the sex worker community during her time as a sugar baby, says that the problem is particularly rife within the celebrity and influencer bubble.

“These people get to tap into the profits of sex workers, often earning a lot more depending on their following, because of their ability to switch off their sexuality,” she says. “In these instances, the allure of this sex appeal can be fostered and distilled by outsiders to capitalise on the association of sex work without taking on the actual stigmas or dangers.”

“It’s great they’re being brought into the fold and finally recognised, but it can do more harm than good when people with immense privilege and access decide to infringe on this work for clout,” she says, cautioning how this can inadvertently put pressure on sex workers to outperform. “It makes things harder for sex workers because it takes away from their hustle, and they can be pushed way beyond the norm within their work.

“Clients don’t just want the stuff they can now find easily on Instagram and OnlyFans, they need more and more.”

Dr Karen’s point casts a different light on some of the figures who have been purveyors of hypersexualised fashion. When Emily Ratajkowski or Kim Kardashian don their fishnets and dominatrix wear, they’re viewed as liberated heroines. But they do so in the safety and security of knowing they can dip in and out of this world as they please. It’s also worth noting that the people who tend to benefit from this spotlight, are conventionally thin, white women when, as Dr Karen notes, this is deeply unreflective of the real-life sex worker community. It’s here we see a large inequality at play, one that dictates who gets to be sexy versus who is relegated to being a ‘whore’.

From the outset, it’s easy to shrug it all off and see women thriving in these trends because things are better for us. We’re sex-positive, we’re in politics, Rihanna is a billionaire, and we’re all about freeing the nipple, bimbofication and facilitating a culture where women can wear whatever they feel most confident in. If that’s eight-inch platforms, a latex mini dress and a studded collar necklace, that’s our prerogative. But as Dr Karen notes, past times of revolution tell us that these trends can actually point towards social decline.

“In times of shifting politics, where we begin to see more restrictive policies, women tend to buck against the system,” she explains. “Dressing becomes a form of agitation, and that’s when we see more risk in clothing.”

As we bear witness to regressive shifts around the world, with conservative governments rapidly gaining in popularity, Dr Karen emphasises how clothing that allows us to reclaim ownership of our bodies, can simulate a sense of freedom and control when we feel these things are being taken away from us.

None of this is to say that fishnets and platforms are off the table – that would be missing the point. The wheels are already in motion, and fashion’s pendulum will forever swing to and from aesthetic trends. In fact, this is what gives Dr Karen projects for the future.

“Connotations around particular fashion signals change,” she explains.

“Even wearing red nail polish was a no-no when I was growing up. It was too associated with promiscuity, and so I wasn’t allowed to go near the stuff when I was younger. Now I see it as a fashion trend everywhere, and that’s where I need to unlearn my own standards.”

As Dr Karen posits, the key to traversing the dilemma lies in engaging critically with fashion’s venality and not losing sight of the bigger picture. There is no female liberation in itty-bitty shorts or braless crop tops without the support of the women who did it first. As much as it can feel trivial at times, fashion does not exist in a vacuum. It has roots, meaning, and can be a catalyst for disrupting the status quo. Trends may ebb and flow towards modesty, but if you look around, you can usually see that they have long had a role to play in social movements. Women are not out there in mini-skirts and flesh-baring cuts because everything is fine, but rather, because it’s not, and it might not like look armour, but it’s one of the few ways we’ve been able to push back.

After all, change doesn’t dress us, we dress for change.

THIS FEATURE IS PUBLISHED IN THE 15TH EDITION OF GRAZIA INTERNATIONAL. ORDER YOUR COPY HERE.