AUSTRALIA: Helen Duroux, the aunt of murdered Indigenous teenager Clinton Speedy-Duroux, has pulled over on the side of the road in Armidale in country New South Wales to talk to me this morning. “Thank you to your people for actually wanting to help. I appreciate it and I feel honored that you want to hear my thoughts,” she says through tears.

“Honored.” It became apparent to me in this moment that the woman on the other end of the phone line deems it normal for people to not really have a lot of time to listen to what she has to say. For Helen, the extraordinary happenings in her life and her family’s lives have been considered unimportant and swept aside by our country’s criminal justice system. And it’s just so wrong.

On January 31, 1991, Helen’s 16-year-old nephew Clinton went missing following a party that he attended with his girlfriend in Bowraville in northern New South Wales.

“We knew it was foul play because we found out that he didn’t take his shoes and Clinton was very, very fussy about always having his shoes wherever he went,” explains Helen.

CLICK HERE TO DONATE TO THE MAKING OF THE DOCUMENTARY ‘THE BOWRAVILLE MURDERS’

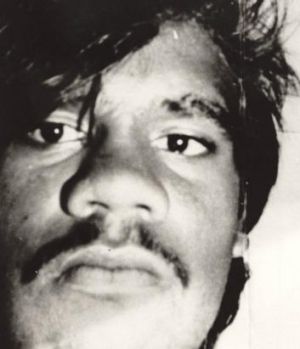

His disappearance was the third in just five months and all were Indigenous children who vanished from the same stretch of road. Colleen Walker-Craig, also 16, had disappeared on September 13, 1990. She was last seen alive at a party in the same area that Clinton would go missing months later. Her clothing items – but never her body – were found weighed down with rocks in the nearby Nambucca River.

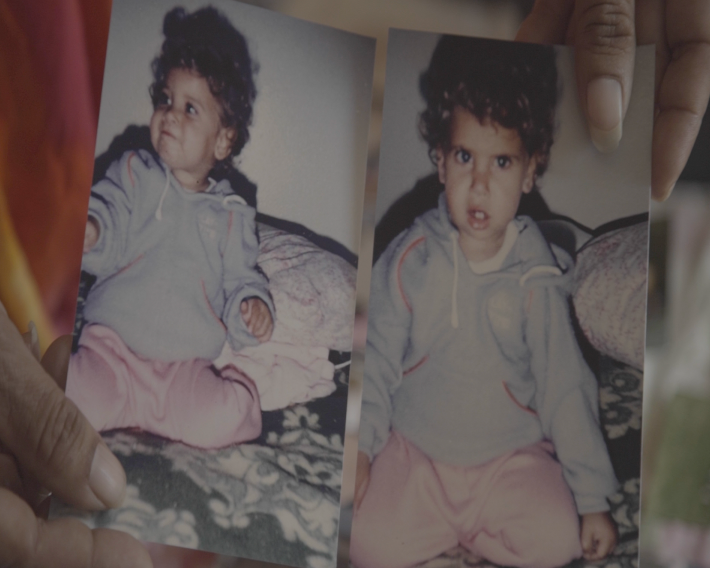

A couple of weeks later, on October 3, four-year-old Evelyn Greenup was reported missing. After a similar party, her mother put her to bed but come morning, she was gone.

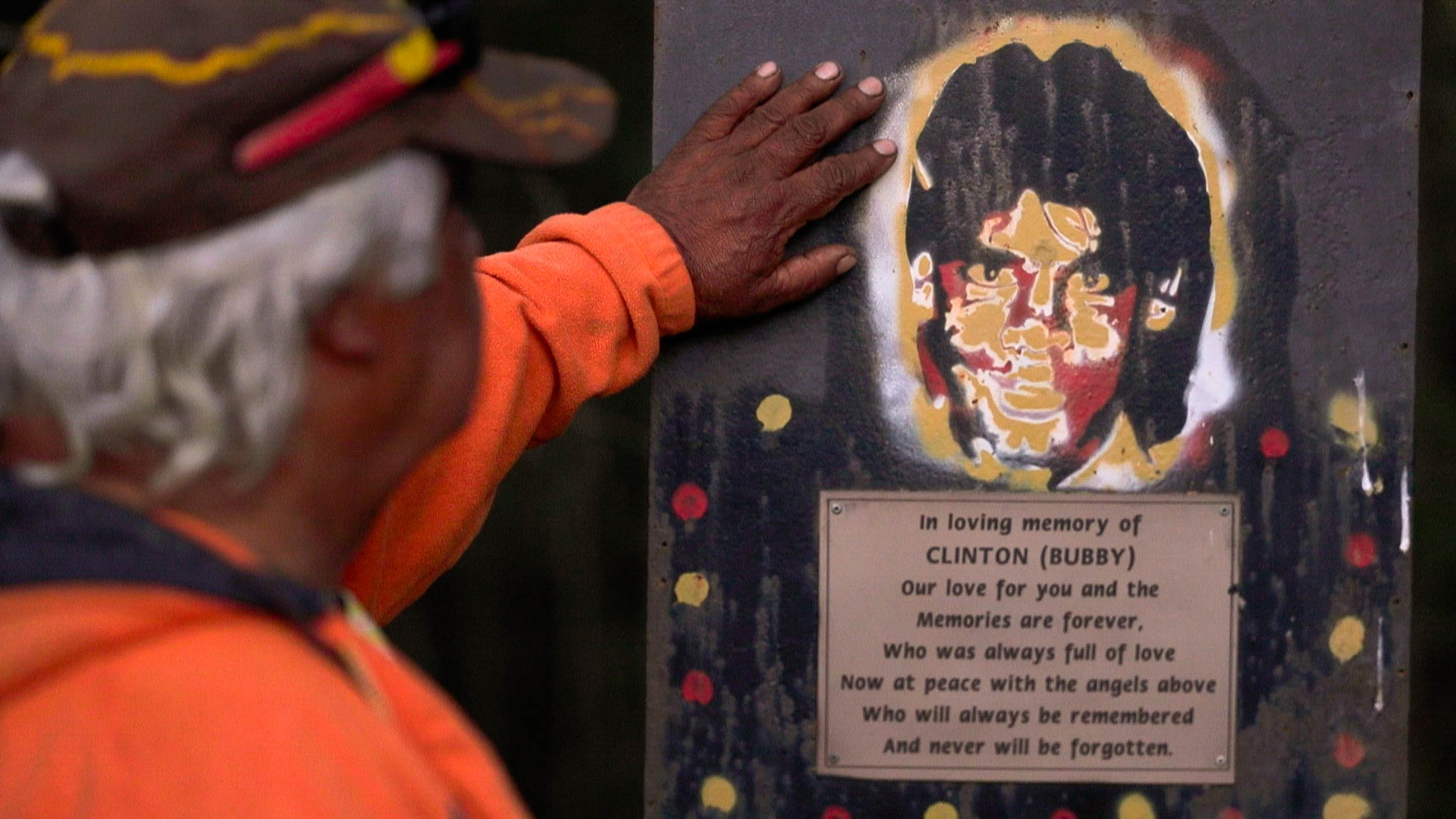

Eighteen days after Clinton went missing, his remains were discovered in bushland about seven kilometers outside of Bowraville. He was wrapped up in a blanket and a pillowcase, items that matched linen in the suspect’s caravan. “The shock and horror of [finding this out] – it’s something I’ll never forget. We were devastated,” Helen says, her voice breaking.

Evelyn’s skeletal remains were found nearby a couple of months later.

On April 8, 1991, a local man, who we can’t name for legal reasons, was charged with Clinton’s murder – but was acquitted of any wrongdoing at his 1994 trial. The same man was charged with Evelyn’s murder but prosecutors decided not to proceed with the murder charge after seeing the outcome of Clinton’s case and given Australia’s double jeopardy laws, they were unable to try the man for both crimes.

“I can’t believe that we all get really emotional 30 years later. It just shows how much this guy was loved and how much it hurts that there’s a guy out there who did this. Where’s the justice in that? He got off scot-free,” says Helen.

After changes to the double jeopardy laws came into force in 2006, the Duroux family held out hope as an acquitted person could now be retried for serious crimes in certain circumstances. But multiple Attorney Generals rejected their appeals.

“It was just devastating sitting up in the high court in Sydney and somebody decided that these children weren’t worth it. They weren’t worth justice. That they weren’t worth another look,” says Helen.

“If it was three little white kids from the North Shore and it was a black man that did it, they would have been in jail rotting.”

While the legal labyrinth is a tricky one to navigate at the moment, Muruwari and Gomeroi filmmaker Allan Clarke is making a documentary – commissioned by the SBS – which investigates the Bowraville Murders: the longest unsolved serial murder case in Australian history. He needs a few more thousand dollars to make the final sum to complete the film by next year.

And that’s where you come in. I’d really love for you to spend some time reading Helen’s interview below – how she describes Clinton in the school play and the constant state of limbo her family has been in for three decades.

And then, if you can, donate to this crowdfunding link to see this documentary get finished. The fundraising window closes on June 30 so we need to act now. Set up through the Documentary Australia Foundation, any donations are also tax-deductible (hello, July 1).

CLICK HERE TO DONATE TO THE MAKING OF THE DOCUMENTARY ‘THE BOWRAVILLE MURDERS’

Today is the day we listen to Helen and campaign behind her for Indigenous people to be treated as equals under the law. In the spirit of listening, the below interview is published exactly as she tells it – and because these children’s lives are worth every bit as much as our own.

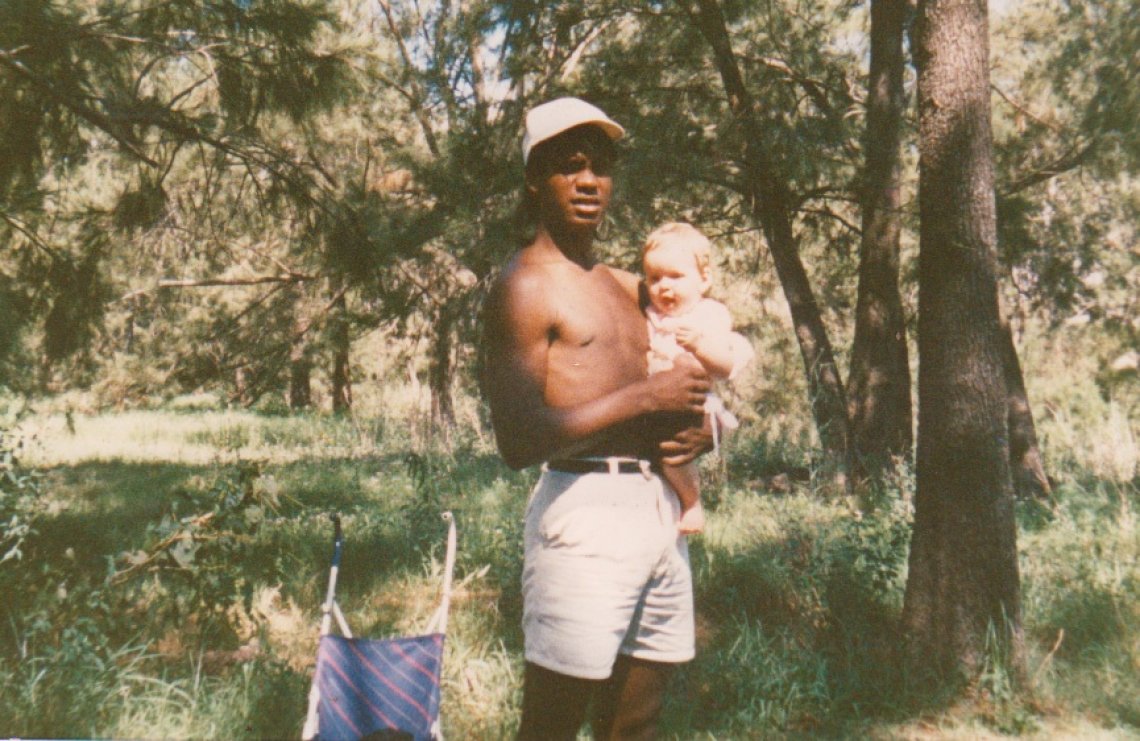

Jessica: I must say Clinton was such a handsome young man. What was he like?

Helen: “He was very, very good-looking. He was very gentle. He loved all the little children – all the toddlers and babies of our families. He always had a couple of young ones hanging off him, purely because he had a beautiful heart and loved little ones.”

What was your last memory of him?

“He turned into a funny little guy. He had a really good, silly sense of humor. I used to do some work with him when he was younger and lived in Tenterfield. I’ll tell you one thing we did with the kids at school, we did a play where we enacted the Aboriginal creation story for the school. We specifically asked that we have all the “uncontrollable” kids (according to the school). We wanted to show the school that these kids are really worth it and they had promise.”

Tell me about the play.

“My ex-husband and I went to the secondhand shop and bought an old fur coat and cut the sleeves out of it because it looked like a kangaroo skin. The collar was turned into something that he would wear over his ears to make it look like a beard. All of the kids we worked with at the time were ‘naughty kids’ according to the school, but when Clinton came on as Old Father Earth, everyone said after ‘Who was the old man?’ He was so good that everyone was convinced that we had an actual old man. When some of the key players there asked me how we got the kids to do what we wanted, we said ‘We treated them like real people.’ That was the difference. That was a lesson that they could have learned from. We gave the kids something to be proud of and a place to show their talents to the whole world. To the whole school. We got the best feedback and all we wanted to do was show you how talented our children are. It wasn’t long after that that he went down to Bowraville to live with his dad.”

That proud feeling would have been something he would have always remembered, I’m sure. It’s hard enough finding your self-worth as a teenager, I can’t imagine how hard it must have been to be an Indigenous teenager in 1990s Australia.

“That’s right.”

When you found out Clinton was missing, did you instantly suspect foul play?

“We were all in Tenterfield but we knew it was foul play because we found out that he didn’t take his shoes and Clinton was very, very fussy about always having his shoes wherever he went.”

“He was always proud of his flash shoes and he never went anywhere without them. As soon as we realized this, we knew there was something wrong.”

What do you believe Clinton’s final movements were that night?

“From what I found out, he was at a party with his girlfriend at the time. After the party starting slowing down, this white man invited him back to his place which was a caravan behind his mother’s place. That’s what this man would do, he would try and get women to go with him in a sexual way. I know he’d always had a thing for Clinton’s girlfriend and it was clear that he wanted to take Clinton out of contention. He invited them back to his caravan for a drink. He had money and he knew if he shouted people drinks or drugs – some yarndy or whatever – he’d always play god and try and win girls over.

So they went back to the caravan and my guess is he slipped something into the drinks of the women so he could have his way with them, that was his modus operandi. This wasn’t the first time that this had happened. We’d heard stories from other women where they’d wake up in the morning with no pants on but didn’t remember what had happened. In my books, he was a serial rapist as well as a murderer. He was always sourcing young girls to have sex with. And if they didn’t want him, he’d put something in their drink to put them out.”

Without being there, but knowing Clinton, what do you think happened in that caravan?

“This is only my personal opinion. My guess would be if he did give Clinton any drugs, it probably wasn’t enough to knock him clean out or take him out of the equation. I feel that Clinton probably came to and caught this guy in the act. I can’t say truthfully, but that’s what I believe.”

Can you remember the moment you found out his body had been found?

“The shock and horror of that – it’s something I’ll never forget. [tears].

I’m sorry for upsetting you.

“That’s OK. We were all home and we finally found out and it gave us a bit of closure that he was gone. We were all devastated. He was very much loved, that little guy.”

And had so much to live for…

“He had his dreams. He was a very talented dancer. He was a very clever little guy. He just went down to Bowraville because he wanted to be with his dad.”

CLICK HERE TO DONATE TO THE MAKING OF THE DOCUMENTARY ‘THE BOWRAVILLE MURDERS’

Do you believe if these cases were those of white children that someone would be behind bars?

“I know that would be the case. When they found Clinton’s body, he was wrapped in a blanket out of that caravan. They matched the blanket and he also had a pillow slip over some wounds on his body. The pillow slip and the blanket matched the caravan. And do you know what happened to that blanket?”

What happened?

“They washed it. The evidence was washed off. Who does that? Who does that to evidence in a murder? You can’t tell me that it wasn’t covered up. That guy’s family had money, they were an old family with old money and that impacted the way the police treated the investigation. We were just a black mob. They didn’t care about us. These people had money and prestige around the town. It was like, ‘How dare you blame this guy. What’s wrong with you?’”

The police inferred Clinton “went walkabout,” is that right?

They said Clinton had been seen walking along the road – that he’d ‘gone walkabout’ – and was trying to hitchhike home. Two years after all of this, I was out at St George and an Aboriginal young man came over to me and we started talking. When I told him who I was, he said, ‘I’m the boy they thought was Clinton walking along the road.’”

When there is no closure, how do you get through your days? How do you live?

“In the back of your mind, you always have hope that something is going to give, someone is going to come forward and the justice system will uphold us. You always have that hope.”

“Although I was speaking to Tom [Clinton’s father and Helen’s brother] over the last week and he said that he’s been told that we’re probably never ever going to get justice. Now we have to work out which way we’re going to have to go in regards to all the wrong things that have happened throughout this whole case. Tom more or less has resigned to the fact that the solicitors have said we can’t take it any further. We’ve been through the high courts – as high as we can go – unless somebody else may have been involved, I don’t see the justice system overthrowing this. But we can always hope that somebody has seen something or knows something, to give us a bit of closure. How could someone not speak up?”

CLICK HERE TO DONATE TO THE MAKING OF THE DOCUMENTARY ‘THE BOWRAVILLE MURDERS’

“My mum started fighting this battle. She’s gone now. We stepped up and now our sons and daughters are taking on the fight. I just don’t want to see a fourth generation have to fight these injustices.”

The death of George Floyd in America and the subsequent Black Lives Matter movement has put a magnifying glass on Australia’s own treatment of its Indigenous population. Do you think that maybe all of this media attention might shift someone’s mode of thought to come forward with some evidence or put pressure on policy makers?

“I can only hope that if somebody has seen something or has been made aware of something that they would come forward. Having all the injustices highlighted overseas, it’s just brought out so much hatred here as well. Over the last few weeks, that’s all I’ve done on Facebook; bat racist people off. People saying ‘It’s not Black Lives Matter, it’s All Lives Matter.’ To that, I say, I know all lives matter, and I’m not saying that all lives don’t matter but it’s just that our lives are at risk – and our kids lives are all at risk more than anybody.”

CLICK HERE TO DONATE TO THE MAKING OF THE DOCUMENTARY ‘THE BOWRAVILLE MURDERS’