“Christian Dior possessed a smooth face, where only the brown eyes mused,” claimed Françoise Giroud, who was the editor of Elle in France from 1946 until 1953, when she and Jean-Jacques Servan-Schreiber founded the newsmagazine L’Express. “Dior didn’t undress you with his eyes; he dressed you.”

Another iconic lady of France is the aristocratic designer Jacqueline de Ribes, who has been on the International Best Dressed List since 1962, when she was inducted into its Hall of Fame. One of Dior’s most devoted clients, she told Natasha Fraser-Cavassoni for her 2014 book, Monsieur Dior: Once Upon a Time, “The first thing we tried on was the inner structure, because at Dior, the inner structure was more important than anything … They were made of double thickness tulle and had whale bones. At the back, there were only hooks so you really needed a lady’s maid or a nimble-fingered husband.”

The critical gaze and a thoughtful inner structure are also the two buttresses of artful beauty on which a museum show is built. Its visual narrative leads you forward in subtle, studious, and even at times elegant ways—as it is now at the Brooklyn Museum, with the exhibit Dior: Designer of Dreams. In such shows, an accrued grace often grapples with academic rigor in a dance that turns into an internal dialogue with the viewer. One sees the beauty presented in a museum, but if the design of the exhibition is successful, it disappears into it—much like the fabric of a garment was disappeared into its structural beauty when it was first being folded and draped and transformed by the harboring hands of Dior, where Paris came to anchor itself once more with some self-respect and pride in the first years following World War II and the occupation by German forces.

Too much to ask of a fashion designer? Not Dior, whose careful demureness disguised just as carefully a determined, keenly constructed ambition. Indeed, his ambition was as structural and designed—take a look at his detailed, expansive 1952 business plan—as the garments that served to garner it.

A large part of his demanding respect for France in the wider world is captured in the Brooklyn Museum’s latest iteration of the Dior retrospectives that have already been seen in London, Paris, and Shanghai. This version focuses on Dior’s presence in America and how he conquered our country with a combination of talent and tenacity—and a lot of purposeful French charm. Dior was, in fact, the first fashion designer to appear on the cover of Time, the most American of magazines. It was for its March 4, 1957, issue—he would die seven months later—and the cover story was both a paean and snide bit of snob-bashing that was itself snobbish in its overly ironic tone—one that limned even its lede—as it pointedly included an array of Americans and their slavish love of the designer: “The swank Ritz cocktail lounge and the grave Plaza Athénée bar were shrill with the sound of American females emitting the ritual cries of greeting as they hailed each other from divan to divan. In the lush Victorian plush of Maxim’s, stumpy men from Manhattan’s Seventh Avenue sat heavily, resting weary feet.”

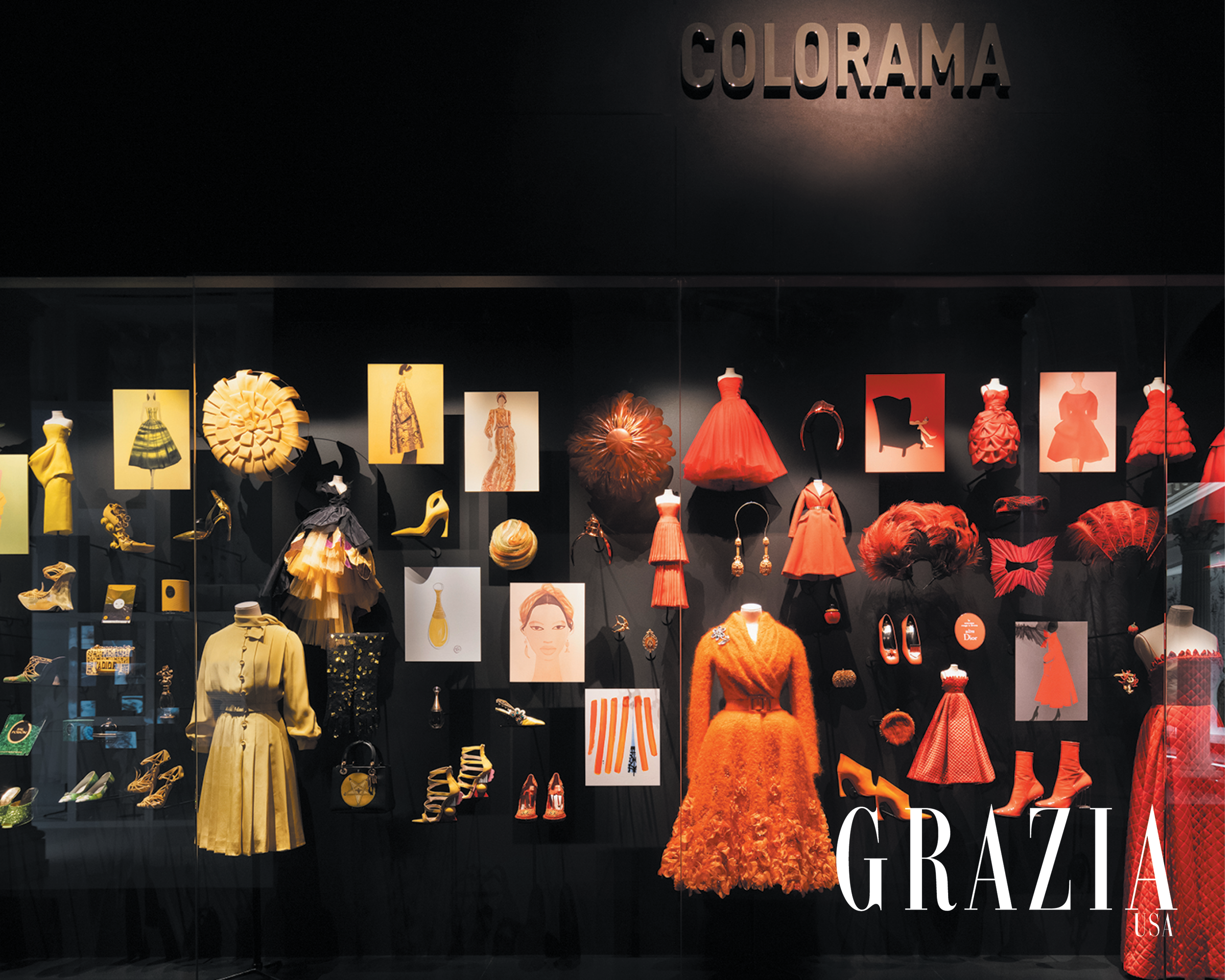

Dior famously favored grays and pinks in his collections because of how pleasingly they complimented his feminine ideal but the use of the latter hue to describe him in the story that millions of Americans at the time read was not meant as a compliment, one presumes, as the writer to-ward the end of the lede described him as “a plump, pink, innocent-look-ing son of a fertilizer manufacturer.”

One thing about America: We love to build you up so we can bring you back down to size. Then, with our love of narratives about redemp-tion, we build you back up once again—as the Brooklyn show heralding the American aspects of Dior’s rise after WWII attests. We assembled this country on aspiration but have always thought of longing—which Dior innately understood and translated into his designs—as a kind of weakness and have looked suspiciously, even woefully, at anyone who considered it a strength.

Architecture has been used to describe Dior’s talent for structuring a garment, but he also understood the female body much as a dancer or choreographer does; he knew how to elongate longing along the lines of a woman’s figure and give it motion. He translated the abstract concepts of longing and beauty—even happiness—into the actualities of his “New Look” hemlines, cinched waists, blossoming skirts, a bit more bosom, softer shoulders, and the very feel of his fabrics. His vaunted shyness was really just a cover for his refusal to shudder at his knowledge of his own artistic power. “Ballet is woman,” Balanchine famously declared. Dior was Balanchine with a bolt of fabric and a balance sheet.

“Dior was, yes, very modest. But what I find interesting about his character is that he was on one hand an artist and then on the other hand a businessman—which is quite rare still—and he took each of those two sides as seriously as the other,” Florence Müller tells Grazia USA. Müller, the Avenir Foundation Curator of Textile Art and Fashion at the Denver Art Museum, which hosted an earlier version of the Dior exhibition, has been considered a leading Dior scholar since 1987, when she mounted a show about him at the Louvre (where she was then director and curator of Union Francaise des Arts du Costume at the Musée des Arts de la Mode). She has curated this latest exhibition along with the Brooklyn Museum’s Director of Exhibition Design, Matthew Yokobosky.

“When you read his memoir, it is very touching how he describes when he arrived in New York and suddenly he is onstage and unprepared and doesn’t speak English,” she continues. “Suddenly he remembers his early years in the theatre and making costumes and he says to himself, ‘OK, I will play the fashionable couturier.’ In Dior’s style, there is a lot about the theatrical and the fact that you can reinvent your life. You rein-vent yourself on an everyday basis. And you create effects with a costume and presence…

“The first section of the Brooklyn exhibition is celebrating Dior in New York,” Müller says, describing the show that has other differences with the earlier retrospectives, including a room filled with the work of American fashion photographers and the Brooklyn Museum’s central atrium of the Beaux-Arts Court being redesigned as an enchanted garden to highlight Dior’s love of gardening and the inspiration of flowers in his work.

“A very important element of the show is that New York was the fashion heart of the conquest of the world, which was very new back then,” Müller continues. “There were many couturiers who did attempt to explore America, but on the scale of Christian Dior there was no other example. It was through the house he opened in New York. It was set in tune with Paris, but also with this idea that American women had their own style, their own lifestyle. He really studied the country and his cus-tomers,” she says, mentioning as well the importance of Neiman Marcus in introducing him to America.

Some American women, however, did not welcome him and his luxuriously confining “New Look” after their experiencing a semblance of equality by working in “male” jobs during WWII and dressing in ways that freed them to do so. These newly empowered feminists pushed back against Dior and those who championed him—which was ironic for a man who depended so much on the talents and guidance of a coterie of close female colleagues in his company, including his muse, Mizza Bricard, whose love of leopard was paid homage in the Bar Suit’s jacket for the Fall/Winter 2021 collection. There was even a group in America—back in 1947 when the “New Look” arrived—that called itself “The Little Below the Knee Club,” with chapters across the country that rounded up the outrage in meetings and demonstrations and signed petitions against the designer.

“In terms of Dior and women and feminism, I think it is very interest-ing to look to today and Maria Grazia Chiuri,” the Brooklyn Museum’s Yokobosky tells me, mentioning the first female creative director at Dior, one who succeeded a lineup of men—Yves Saint Laurent, Marc Bohan, Gianfranco Ferré, John Galliano, and Raf Simons—all of whom are highlighted in this latest exhibition.

“In Maria Grazia’s Spring 2020 collection, she collaborated with Judy Chicago, who did the iconic ‘Dinner Party,’ which is a feature of the Brooklyn Museum show,” he continued. “So, looking at the work of Maria Grazia we see how she brought the feminist narrative forward, especially with her first collection in which she included T-shirts that said ‘We Should All Be Feminist,’ quoting the writer Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie. So, while Dior might not have been a feminist, he definitely was promoting the ideals of women as part of his practice.”

Each time there is an iteration of this type of major fashion retro-spective, about two-thirds of the dresses have not been exhibited before. “This is the main difference with the Victoria & Albert exhibit and the one in Paris,” says Müller. “This is connected with the fragility of fabric. You can’t display for too long the fabric. Perhaps the stories are similar, but you have to change the way they are displayed. For example, the Marc Bohan section is expressed with dresses that have never been displayed before except for the dress that is an homage to Jackson Pollock. This is a great thing about the Brooklyn show.”

The pristine state of so many of the garments displayed is because of the care of the Dior preservationists back in Paris—including Director of Dior Heritage Soizic Pfaff, who oversees a dozen archivists on her staff. “The archive only really began when Mr. Arnault bought Christian Dior in the early 1980s, so it wasn’t until 40 years after the beginning of the company that it was started,” Pfaff has said. “What we are trying to do is work with museums and collectors and clients to create a complete inventory of every single garment around the world.”

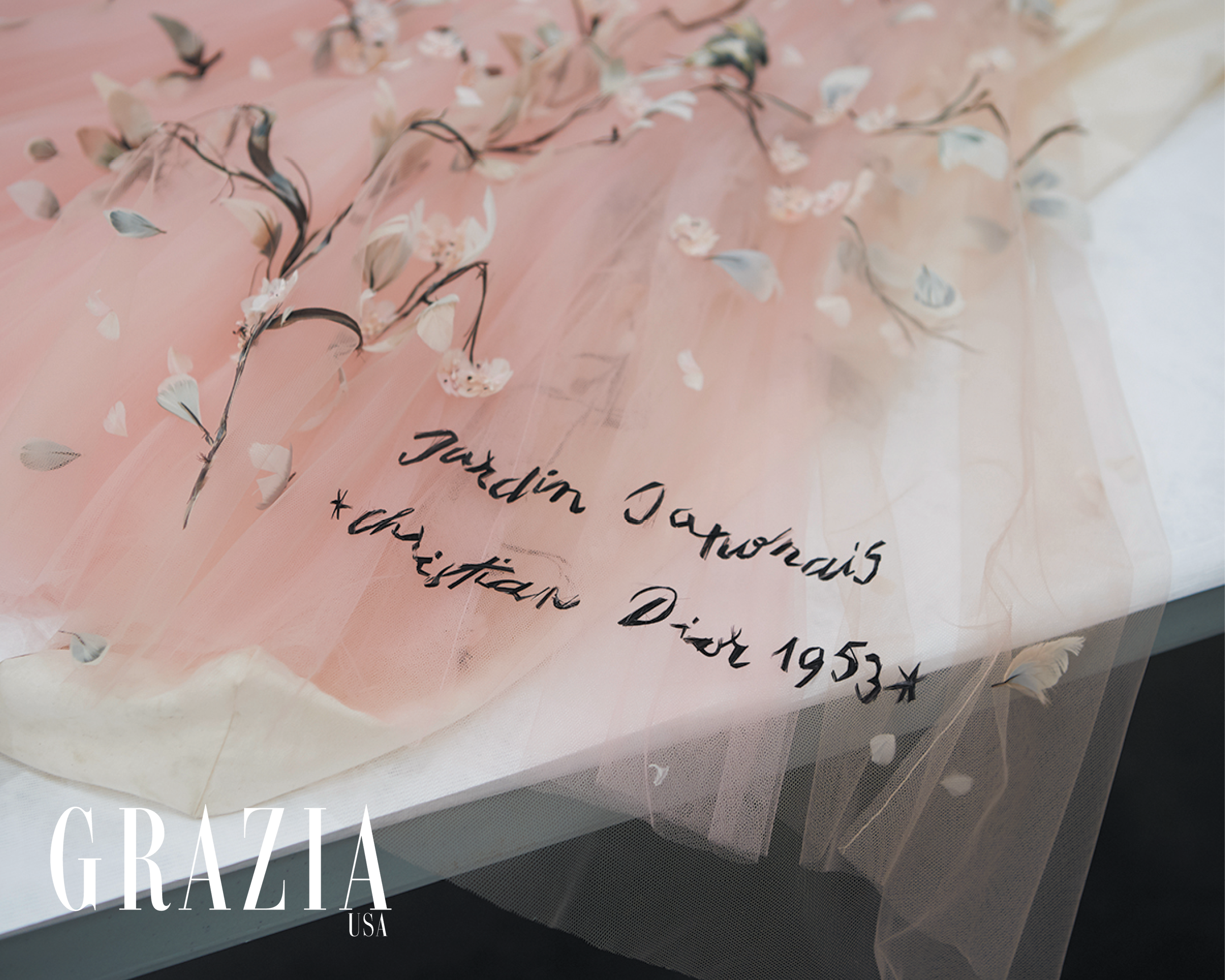

Inside the archive mannequins have been designed to fit the shape of each garment encasing them. There is a Dior library. Documents and original sketches by Dior and the fabulous ephemera of a fashion house are stored in boxes labeled carefully with calligraphy, each box the “trianon gris” color that Dior reinvented from the pearlized gray of the 19th century. It is the shade of gray that recurs within his collections and continues to be highlighted by the house today.

“‘Dior brought that grey back and it was the best,’” Fraser-Cavasonni wrote in her book, using an archived quote from Grace Lady Dudley about Dior. “‘Both modest and luxurious, it set the tone of the house and actually summed up Dior’s character. … Humble and charming, he was totally unlike others in the fashion world.’” (A fashionable literary aside: Fraser-Cavasonni’s mother, Lady Antonia Fraser, was the English translator for Dior’s memoir.)

Dior, sounding like an archivist himself, wrote about care as the key to elegance in another of his books, The Little Dictionary of Fashion: “I will only say now that elegance must be the right combination of distinction, naturalness, care and simplicity. Outside of this, believe me, there is no elegance. Only pretension. Elegance is not dependent on money. Of the four things I have mentioned above, the most important of all is care. Care in choosing your clothes. Care in wearing them. Care in keeping them.”

Ultimately, the arc of Dior’s life from young gallerist showing avant-garde art in Paris in the 1920s and 1930s—he didn’t become a designer until he was in his forties—to his being the subject of museum exhibitions around the world is as sumptuous in its symmetry as a Dior dress itself.

“One of the quotes that was important to me from Dior was that while fashion was an ephemeral art, he said for himself it was a means of self-expression that was equivalent to architecture or painting,” says Yokobosky. “When Florence and I were working on the 1950s New York section, I started thinking of other artists in our collection in Brooklyn who were active at the same time and perhaps thinking about shapes and silhouettes and color. So, in the 1950s section we’ve included a painting by Ad Reinhardt, a black sculpture by Louise Nevelson, and a folding screen by Ray and Charles Eames. I think if you look at the artists who were working contemporaneously with Dior at the time, you really do feel that fashion isn’t necessarily an ephemeral art. It’s an art that can stand in conversation with other kinds of art from that time.”