I watched novelist Flora Collins grow up. Her mother Amy Fine Collins is a former colleague of mine at Vanity Fair, and a friend. I always thought of Flora as Eloise. Indeed, her mother—long, lean, lovely, deeply stylish, deeply talented Amy who is not only a writer herself but also an official arbiter of the International Best Dressed List—is a kind of combination of fashion editor, Halston confidant and Best-Dressed-Listed D.D. Ryan and the long, lean, lovely, deeply stylish, deeply talented Kay Thompson who wrote the Eloise books after Ryan “godmothered” them into being by introducing Thompson to the illustrator Hilary Knight. There is a direct line in my own narrative mind from Ryan to Thompson to Knight to Fine Collins to Flora. The 28-year-old novelist not only has a talent all her own but also a very specific kind of sophisticated New York lineage which has never been about genealogy alone, but also the congeniality of likeminded souls blending themselves into a treasured tribe of marvelously fabulous misfits who, in turn, fit into designer clothes in ways that they didn’t fit into earlier tribes that didn’t deign them worthy of inclusion during their childhoods. Such members of such an indigenous New York tribe reconfigure such childhoods into adulthoods filled with velvet ropes and the right restaurants and the kind of transactional gallantry and ladylike learnedness found at art galleries and ballet galas.

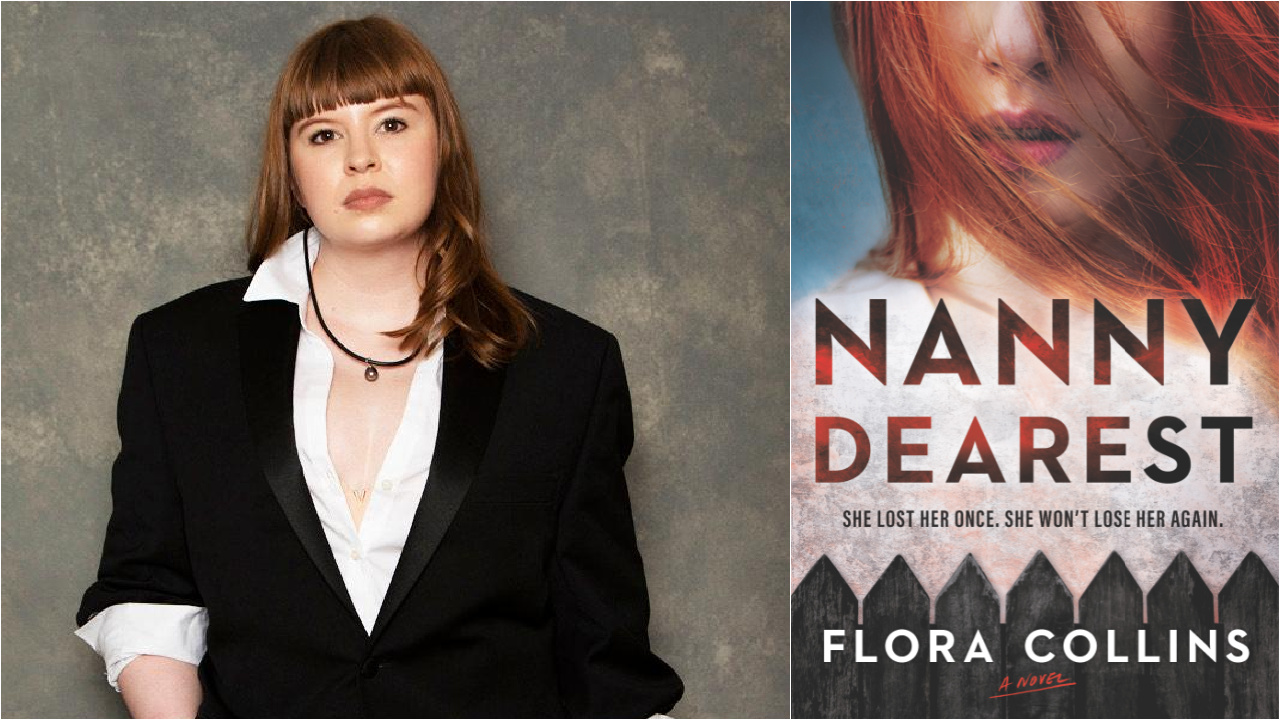

Flora’s father, Bradley Collins, Jr., teaches art history at Parsons—more sophisticated New York lineage—so I was bit surprised that her first book wasn’t a biography of an artist or a fashion designer but a psychological thriller titled Nanny Dearest, a title, one presumes, used to evoke both the lurid movie Mommie Dearest as well as the social satire The Nanny Diaries, the New York Times bestseller that skewered Upper East Side privilege, the very kind that cosseted Collins during her school days at Chapin before she headed north to attend Vassar. Flora’s writing is subtle—there is a sentence-by-sentence sensuality to it that never turns purple or vulgar. She never strains for the right word or phrase. The struggle is there in the psychological tug-of-war going on between to the two main characters, but never in the writing itself. It is a balance that even more seasoned suspense writers often go wobbly about when trying to strike it. Flora never wobbles.

Julia Roberts read the audio book of The Nanny Diaries and I could, in fact, envision Roberts playing the role of the ex-nanny in Collins’s book if it were made into a Netflix series, which I hope happens. The plot of Nanny Dearest—which alternates chapter-by-chapter with the present giving way to the past before heading back to the present again—revolves around the ex-nanny reentering her earlier charge’s life after the young woman’s father dies suddenly leaving her a twenty-something orphan since her mother had died of cancer while the nanny was still obsessively looking after her, a rekindled obsession that the newly orphaned young adult mistakes for the maternal love she has yearned for all her life. But why did Flora choose to write fiction—and a thriller at that—and not nonfiction? She’s even turned in her second novel to Mira Books, an imprint at HarperCollins, where she signed a two-book deal.

“I’ve always been a fiction gal,” she tells me when she Zoom calls me from her apartment in Brooklyn Heights. “Even from the age of 3, I always told childhood stories to my parents. Not lies. But imaginative stories with a beginning and middle and end with made-up characters. If you look back at my old report cards when I was at elementary school, they all mentioned that Flora really loves to read and has a skill and talent for storytelling. It has been this prolonged thing. But because my mom is my mom she was very supportive of me pursuing that, being a teller of stories. It was sort of expected that I would have this artistic endeavor. My dad, too.

“I was a huge Lois Duncan fan as a kid,” she continues, citing the Young Adult fiction writer who pioneered horror and suspense and thriller books in that genre. “I also loved R.L. Stine. All these dark horror people. Duncan was writing in the 1970s for teenagers, but all of her stories are very dark. She was a big influence. Sara Shepard as well. She had a huge thriller influence on me,” she says, mentioning the author of Pretty Little Liars. “They are all character-driven books. I personally prefer character-driven books.”

Her own lead character Sue in Nanny Dearest is longing for maternal love. Was she projecting in some way about her own mother?

“Obviously it’s fiction. I was not basing anyone on anyone I know. But I am very intrigued by mother-daughter relationships. I think they are so chockfull of material. The book’s title is obviously a derivative of Mommie Dearest. That’s already impressed upon you before you start reading. I just think there are so many emotional layers that you can excavate with mother/daughter relationships. Part of what informs that for me is that I do have this larger-than-life mom who is great and with whom I’m close. But I am in the shadow of Amy Fine Collins for, you know, my whole life. But I am not resentful of the shadow.”

“Find comfort in the shade of it,” I suggest.

“Yes. Exactly. Thank you.”

Mira Books’ press release states that the plot of the book is based on real-life events in Collins’s life. Were the most traumatic narrative turns in the book specific to her own story growing up?

“We had a wacky babysitter,” she says. “It’s loosely inspired on that. I want to emphasize this. I don’t want people thinking I was kidnapped by my nanny. It was loosely inspired by this babysitter that I had who was a pathological liar. She kind of escalated in her lies and it was this unsettling experience because, of course, you want the person who is taking care of your child to be truthful.”

As I was reading the book—it’s a can’t-put-it-down thriller when the plot really kicks in—I kept thinking the character of the nanny was a classic disordered malignant narcissist based on the seductive behavior Collins so brilliantly conjures, then the lying, then the gaslighting, then the turning against the person who recognizes they are being gaslighted. It was rather textbook. I wondered if Collins had researched such mental illness before embarking on the writing of the book – or was it all just instinctual on her part.

“It’s funny that you say that because I actually gave it to my therapist to read and asked what mental illness would you give the nanny? What would you diagnose her with? And one of the diagnoses she came up was malignant narcissism. So you’re right on the nose, Kevin.”

Another thing I was curious about was the music Collins listens to, and if she listens to any when she writes as a kind of soundtrack to the narrative she’s creating. In the book, Odetta’s music makes an entrance.

“I can’t really listen to music when I write because I can’t focus on my own writing if I have words in my ear,” she says. “My favorite artist right now is FKA twigs. She’s British. She’s also really good at eliciting emotionality. I’m more a bit stiff-upper-lip. I’m not a super emotional person. But she is someone who can really get me in my feelings. But I wouldn’t listen to her while writing.”

Another writer who attended Vassar, Collins’s alma mater, is poet Elizabeth Bishop who wrote one of my favorite poems, One Art, which is about the art of losing and it being no disaster. It is a poem about loss and Flora Collins’s book, although a thriller, is also a meditation on loss and grief and how it can cause real disaster—sorry, Elizabeth Bishop—and trauma in one’s life. At the end of Bishop’s poem, she writes: “It’s evident/the art of losing’s not too hard to master/though it may look like (Write it!) like disaster.” I read Flora the whole poem at the end of our Zoom conversation and told her those last lines could even be a kind of mission statement regarding Nanny Dearest. Let’s add Elizabeth Bishop to Flora Collins’s artistic lineage.