BY MICHAEL KAPLAN

REPORTING BY NICK HARDING

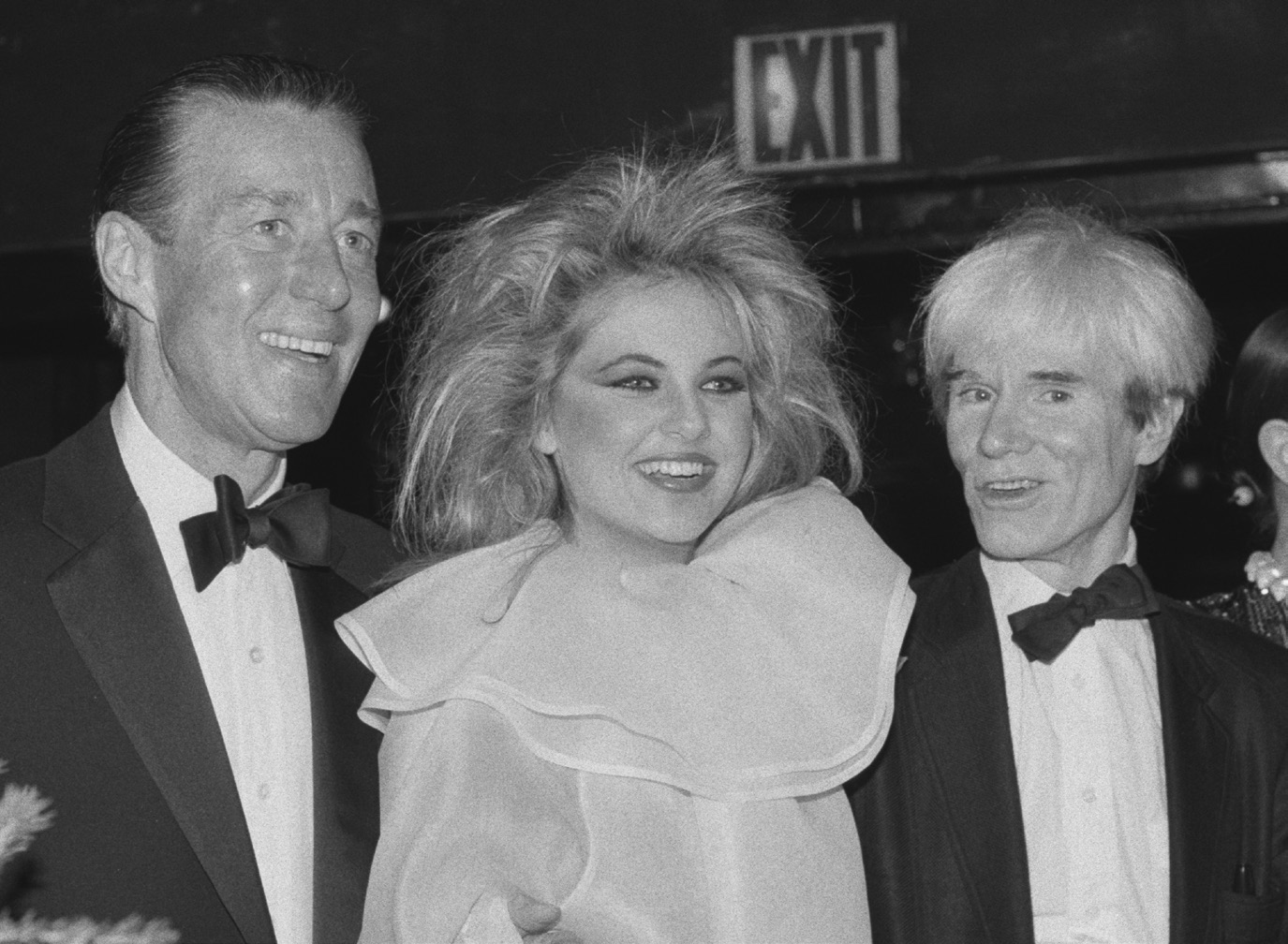

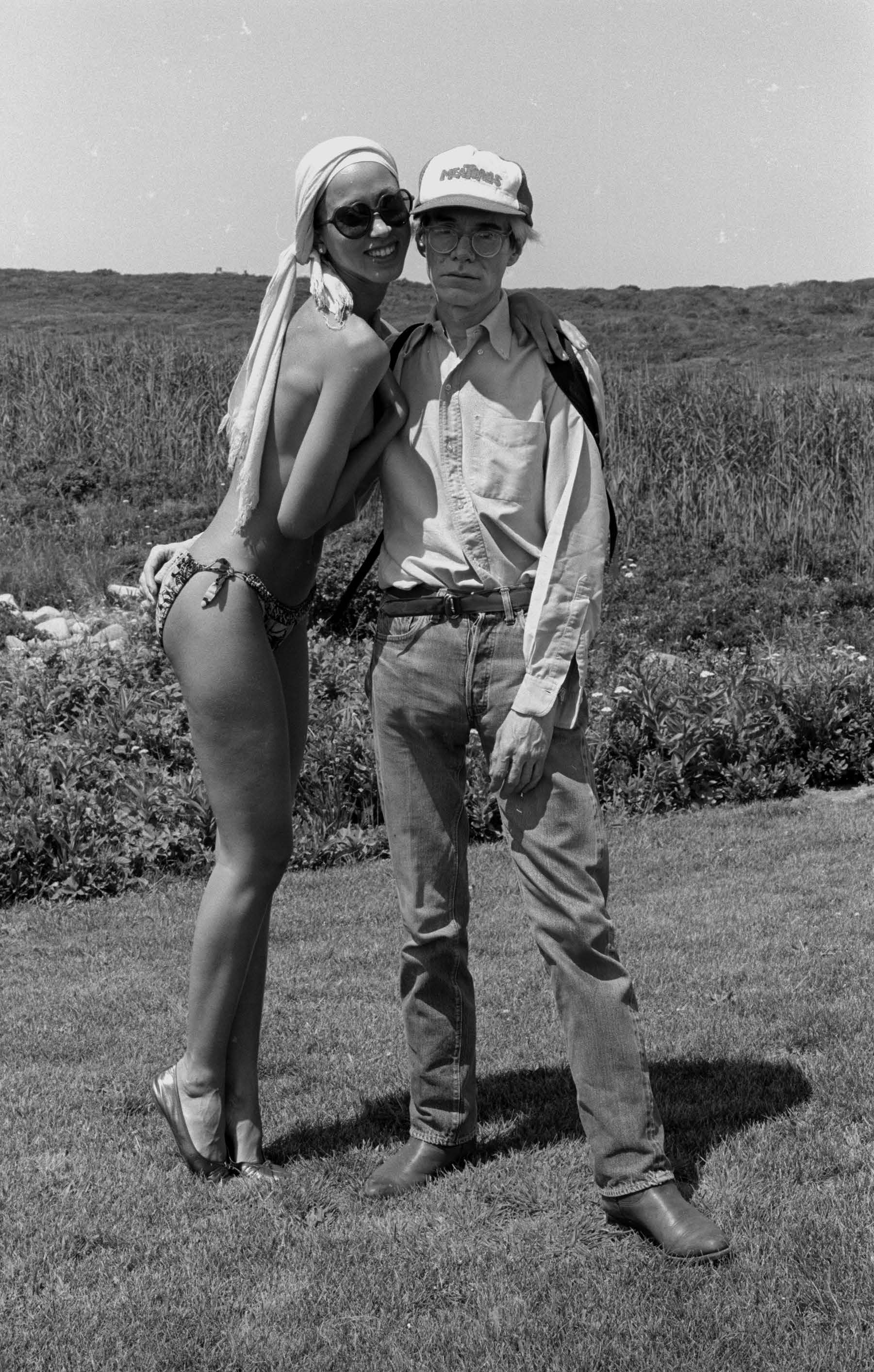

PHOTOS BY CHRISTOPHER MAKOS

The walls were free of tinfoil. Outside, the sun shone bright, unblocked by clouds of cocaine. Andy Warhol’s Montauk retreat—known as Eothen (“from the east” in French) —was in many ways the polar opposite of the frenzied milieu he cultivated at his Manhattan Factory. For that very reason, the clifftop estate became a secret respite for even the most debauched of his party pals: designer Halston, singer Liza Minelli, and model Pat Cleveland among them. The privacy that they relished at the easternmost point in America has consigned many of the memories of that time to history. Now, GRAZIA Gazette: The Hamptons invites you inside the Hamptons’ most exclusive enclave ever.

For visitors, Warhol’s seaside home didn’t exactly telegraph the fact that there was a world-famous artist in residence. Designed by famed American architect Stanford White, it was a 5.7-acre estate comprised of a luxe main house, four guest cottages, a garage (the Hamptons home to Warhol’s Rolls Royce), horse stables, and exactly zero of the pop art phenom’s own work.

“There was no Warhol art in the house,” Christopher Makos, a photographer who frequently collaborated with Warhol, tells the Gazette about the rustic property purchased for $225,000 in 1972 by Warhol and his manager/filmmaking partner Paul Morrissey. “It was a great place where Andy could take off his ‘Andy Warhol’ suit.”

“Nobody was there except for the closest of close friends,” Makos continued, including the aforementioned Halston, Minelli, and Cleveland (who Makos refers to as a “Halstonette”). Even the hordes of fans that surrounded him in the city largely stayed away.

Said Makos, “There were no collectors. Crazy as it sounds, Montauk was too far for them to go.”

Indeed, Montauk was quite a departure for Warhol himself—a man who was far from a beach boy. Alabaster-skinned and rocking an ever-present hairpiece that was known to fly off in the Hamptons wind, Warhol saw the property as less of a dream come true than as an investment. Warhol rented out the property and invited guests that could help boost his profile.

Jacqueline Kennedy and Lee Radziwill stayed there in 1972 with kids Caroline and JFK Jr., after which Warhol joked about putting a gold “Jackie slept here” plaque above the bed in which JFK’s bride had slept. Avant-garde filmmaker Jonas Mekas filmed the kids dancing around to the Rolling Stones’ Sticky Fingers album.

Meanwhile, the Stones would later camp out at Warhol’s pad during the summer of ‘75. The band rehearsed while shirtless Keith Richards made English breakfast in the kitchen and Mick Jagger swanned around in a Missoni sweater over a T-shirt that read: “Linda Ronstadt QUEEN of L.A.” The nearby Memory Motel even inspired a song on the album.

According to Montauk Life magazine, Mick was known to unwind with a bottle of Grand Marnier at the local dive Shagwong Tavern while then-wife Bianca made herself at home in the joint’s kitchen, shucking clams and organizing their take-out dinners.

During the summer of 1982, Warhol began renting out a cottage at Eothen to hard-partying designer Halston. (The scripted Halston series on Netflix gets it wrong by implying that Halston bought a home in Montauk, though he did purchase undeveloped acreage.) Ever the businessman, Warhol continually fretted that the designer was getting too good of a deal: Halston paid only $40,000 per summer when another potential tenant was willing to pay twice that.

Despite the discount, Warhol rationalized that the famously fastidious Halston would at least take decent care of the place. To sweeten the deal, Halston outfitted the property with his own furniture, all of which was much more chic than the dusty stuff already there. Of course, he brought along bouquets of his beloved orchids as well.

Another upside: Warhol was able to visit his own property as a guest when Halston was in residence. Sometimes he’d even catch a ride on Halston’s private jet. The only drawback? A weekend with Halston meant hours listening to his never-ending stream of outré business ideas.

Case in point: As famously captured in The Andy Warhol Diaries, Halston—who had shocked the fashion world by creating a line for down-market J.C. Penney — once told Warhol, “Oh, darling, wouldn’t it be grand if your paintings cost a dollar and you could just cover houses all over the world with them?” Warhol successfully kept his mouth shut in the moment, but he did write disparagingly in his diary about the “J.C. Penney concept.”

Perhaps even more notorious than Halston’s devotion to the mass market was, of course, his rampant drug use. However, Makos—whose photo exhibit including images of Warhol goes up on July 10 at MM Fine Art in Southampton—remembers that Montauk was a whole other story. “Nobody took drugs there during the day,” he insists. “People went there to take a vacation from everything. It was surfers and fishermen with nothing going on.”

He says, “Montauk was more a place where people would smoke a little pot rather than do cocaine.”

In the 1980s, however, greed was good, and private chefs, private jets, and cavorting supermodels became the order of the day at Eothen.

When notorious womanizer and artist Peter Beard rolled through, “he was either with a cool girlfriend or looking for a cool girlfriend,” says Makos. Indeed, in his Diaries, Warhol writes about witnessing Beard making out with glamorous Helmut Newton model Margrit Ramme while Beard’s former flame Barbara Allen looked on helplessly and Dick Cavett told Polish jokes.

Enjoying all of that must have been something of a challenge for Halston during the summer of 1984. He was hiding out in Montauk as rumors swirled about him being pushed out of his own company. According to the biography Simply Halston by Steven Gaines, fashion reporters tracked the designer to Eothen and he coolly told them (probably while wearing swim trunks, his slender chest puffed out, a cig emoting smoke from between his lips), “Is that what they’re saying? Well, it’s not true. No way.” Later that year, Halston attempted to buy back his ready-to-wear and made-to-wear businesses. The buy-back bid failed and he did indeed lose some commercial rights to his own name.

For Halston, it was not only business troubles that might have sullied his Montauk moments. It was also man trouble. He was perpetually on-again, off-again with the volatile, drug-addled, and reportedly well-endowed Warhol muse Victor Hugo. Hugo famously destroyed a Warhol portrait of himself, insisting that his damage improved upon the original, and he once got so violent in the Eothen rental that Halston retreated to his limo and fled to Manhattan. In ‘84, as Halston’s empire crumbled, turncoat Hugo offered to provide evidence that would harm Halston in the event of a lawsuit.

On another occasion, according to Halston, Warhol’s Montauk retreat helped to provide sanctuary and succor for a freaked-out Liza Minelli. Drinking, drugging and paranoid about the plummeting Skylab satellite falling on her head, Minelli spent a weekend night with Halston on his front porch at Eothen. He insisted that the satellite would fall safely a few hundred feet away, and somehow she believed him. So, they ate dinner outdoors and awaited the crash until word came that Skylab had dropped into the Indian Ocean. According to the book, at that point she was able to relax and get some much-needed sleep.

When Warhol died in 1987, it was the end of an era—both for the world at large and for his Montauk hideaway in particular. About 15 months after Warhol’s passing, Halston was told that his rent would double. Unable to afford the increase, he moved out. Three years later, he died from complications brought on by AIDS.

In 2007, the property was sold to J. Crew CEO Mickey Drexler for $27 million. The most recent purchaser—paying $48.7 million in 2015, for just part of the compound—is gallerist Adam Lindemann.

Looking back on the halcyon days at Eothen, long before Montauk became a desirable destination for most New Yorkers, Makos described it as “creative, interesting people trying to pretend to relax.” The more things change in the Hamptons, the more they stay the same.