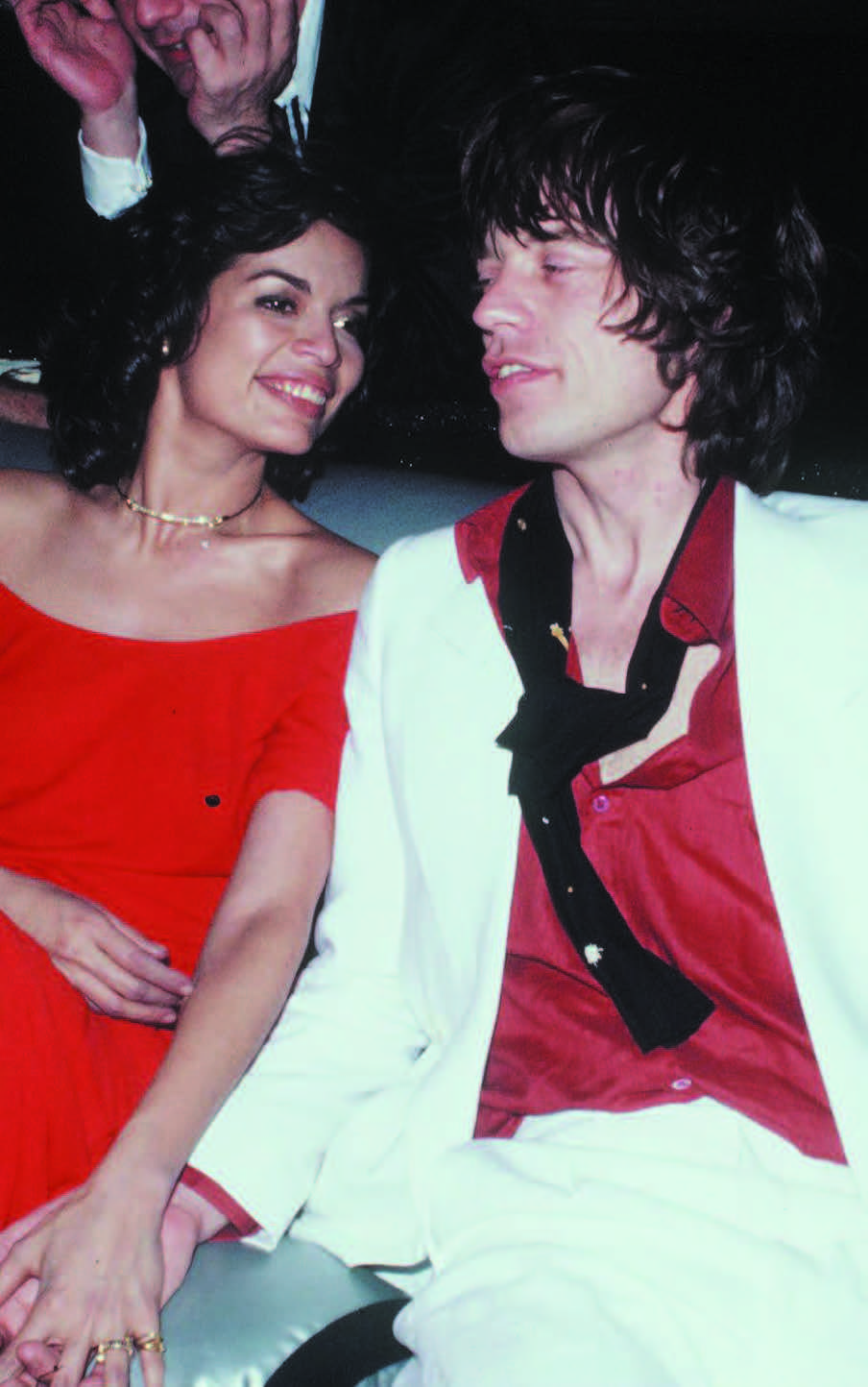

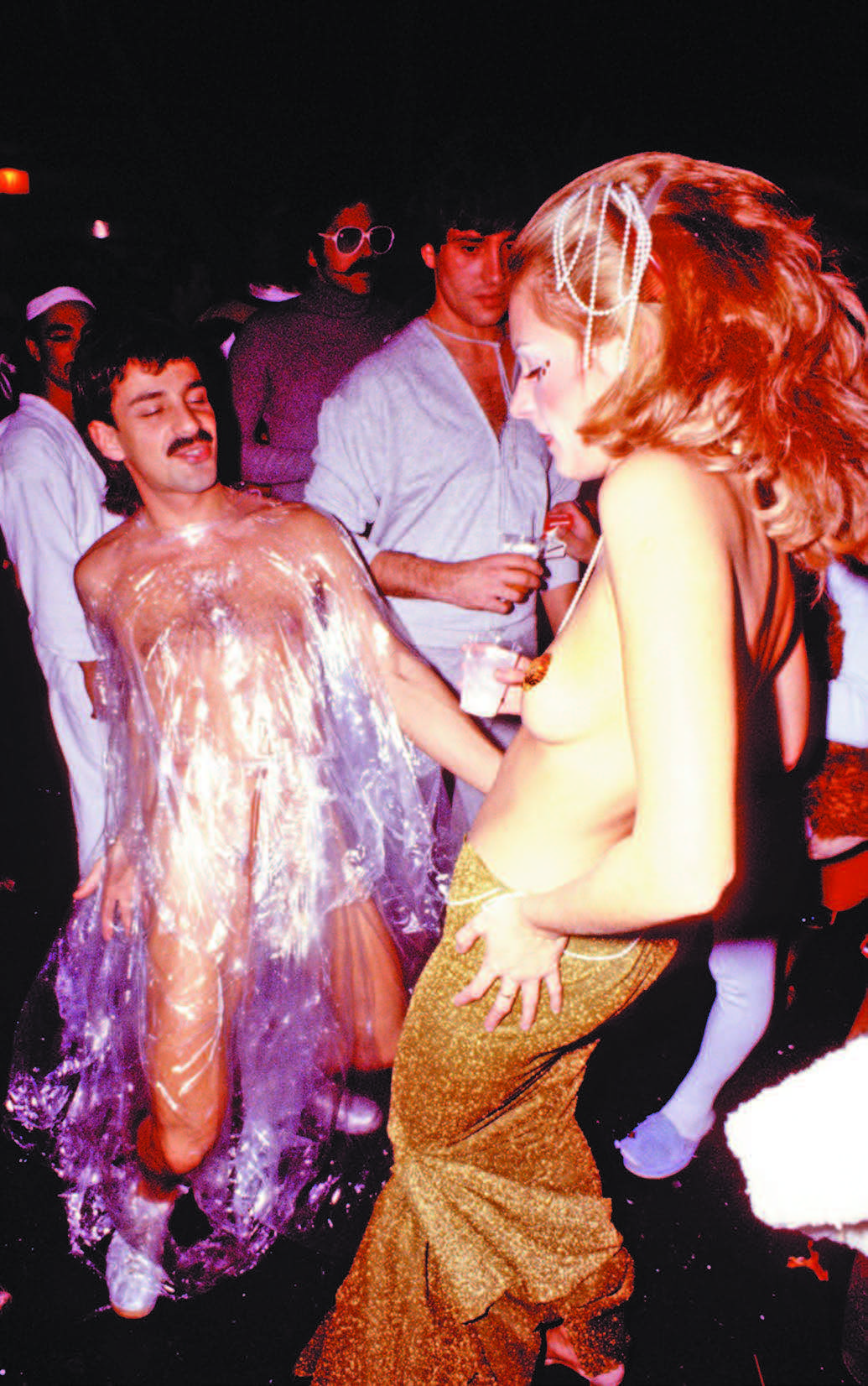

Disco was over-the-top, outrageous, and drug-drenched — and Studio 54 was a disco like no other. Beyond the hallowed doors of the former TV soundstage on a dingy stretch of West 54th Street in Midtown Manhattan, legal and moral boundaries were shattered night after night by the most famous — and possibly most debauched — people on earth. Late 1970s superstars Elton John, Andy Warhol, Truman Capote, Bianca Jagger, and Diana Ross were just a few of the A-listers who counted themselves among the era-defining joint’s elite regulars. None of them, or anyone else, could ever have imagined the way it all would come crashing down. Now, for the first time ever, the ones who share it firsthand speak to GRAZIA USA exclusively about what they saw inside the most exclusive and legendary nightclub of all time. If you’ve seen the iconic club depicted in Netflix’s new hit series Halston, just know this: That’s the PG-13 version.

Studio 54 was a phantasmagorical dreamscape, teetering always between a dream come true and a nightmare. Throughout the course of any given evening, a giant, anthropomorphized crescent moon, with a coke spoon pressed to its nose and eyes flashing red, hovered over the room like a Peruvian-flake deus ex machina. On the dance floor, revelers took their cues and engaged in snorts of their own – often hoovering so-called “party favors” allegedly supplied by club owners Steve Rubell and Ian Schrager. The costs and recipients of those favors were carefully noted in expense logs that were eventually confiscated by the IRS and scrutinized by the Southern District of New York’s Assistant United States Attorney Peter Sudler. “I was astonished at the [blatantly detailed] record keeping,” he marveled, recalling evidence from a 1979 case against the club owners. “I had never seen that before.”

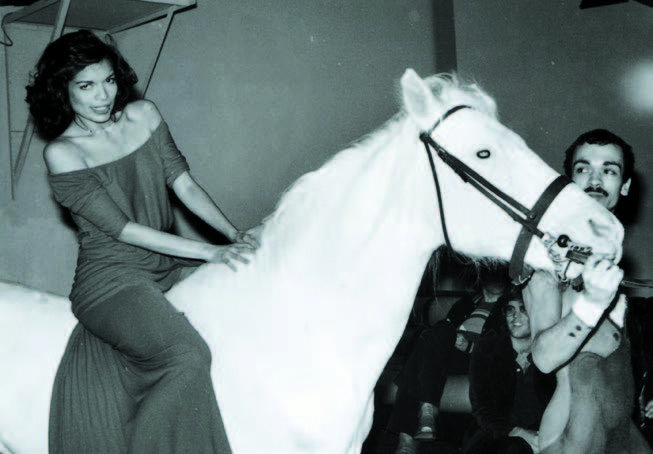

Prior to prosecutors snooping around, though, nocturnal escapades were over the top: Bianca Jagger riding a white horse across the dance floor, fashion designer Valentino Garavani presiding over his own three-ring circus, or Grace Jones doffing her clothes so often that a jaded employee described it as “boring.”

As recalled by Myra Scheer, who served as assistant to both Rubell and Schrager, and worked the inner door as a “troubleshooter,” near where people passed through what she called the “corridor of joy” as admission to Studio was secured, “Every night was a great night. You were never left wondering where the people were. Nights [inside] started slowly, with tons of people waiting outside to be handpicked.”

Once in the club, customers got so frisky that the balcony was eventually covered in rubber so that sexual fluids could be easily hosed off at night’s end. To celebrate the 50th birthday of Andy Warhol, she says Rubell dumped 800 $1 bills over the lucre-obsessed artist’s head. It would later turn out that the sum was recorded as an expense, attributed to Warhol.

As things later unraveled for the club and its owners – all of whom all wound up in jail under various pleas related to income tax evasion – Warhol told New York Magazine of the attribution, “Why would Steve [Rubell] do that? … No wonder people are afraid to go there now.”

Just a year earlier, however, Big Apple scenesters were afraid to not go there. Crowds thronged to get in, pushing up against the famous velvet rope, originally placed at the club’s entrance to keep the then-seedy neighborhood’s hookers at bay. Later, of course, the plush barrier became a symbol of nightlife exclusivity.

Warren Beatty, Henry Winkler, and Nile Rodgers were all snubbed at the door. Quaaludes were allegedly handed out like breath mints by Rubell, and some used the chemical inspiration to start their own party outdoors. Supposedly, it was not unheard of for stoned, frustrated strivers to resign themselves to having sex while awaiting entry. “Steve loved giving out Quaaludes; if you told him you didn’t want one, he’d say, ‘Just take a half,’” said former Interview magazine editor Bob Colacello in the documentary Studio 54.

Gatekeeper supreme was Marc Benecke, who said that he “fell into the job when I was 18 years old, met Steve and he asked me what I was doing for the summer.” From 1977 until 1980 – the glory days of Studio’s reign – Benecke ruled as one of the most powerful people in night life; so much so, that Benecke, who now co-hosts the Marc & Myra Show on the Studio54 channel of SiriusXM, along with Myra Scheer, sometimes would be walked home with a bodyguard so that he could be protected from disgruntled nobodies who nursed grudges over being rejected.

This year marks the 40th anniversary of Studio 54’s last gasp – when nightclub aficionado and fan of 54 Mark Fleishman reopened the glitzy joint after it was shut down earlier in 1981.

“Studio 54 sucked people in, luring them back night after night,” Fleishman wrote in Inside Studio 54, his memoir of those good old days. Fleishman described that allure as “affecting their personalities and emboldening them to do things they might not otherwise have done.”

Maybe the same can be said for the owners.

Back in the late 1970s, the party seemed like it would never end – until a rather anonymous, disgruntled ex-employee by the name of Donald Moon pulled the plug on the debauched proceedings. “As far as we knew he was good to work for,” recalled Benecke. “He had a good temperament.”

Or maybe not. While a rumor swirls that Moon, now deceased, had tax problems, which led him to report Studio 54 owners Schrager and Rubell to the Internal Revenue Service in exchange for leniency, Sudler makes it sound simpler than that: “He was angry about being passed over for a promotion.”

“He contacted the IRS and alleged that skimming was going on [i.e. that Studio’s proprietors were reporting only some of their revenues to the IRS as taxable income and keeping the rest without paying taxes],” Sudler said. “He alleged that there was a second set of books” – along with bags of money and drugs – “kept in the ceiling tiles. Based on that, we got a search warrant.” Amazingly, the obituary that marked Moon’s 2015 death depicts him laughing and stated, “He loved to talk about his time at Studio 54 and all the amazing people he was fortunate enough to meet.” According to Sudler, Moon wanted nothing in the way of compensation if those amazing people – including investor Jack Dushey, who earned his money in real estate – proved to be guilty of the charges and resulted in remuneration for the government. He only wanted placement in America’s federal witness protection program.

Whatever Moon told the IRS must have been convincing. On the morning of December 14, 1978, a reported 31 agents pulled up to the club and banged on its door with a search warrant in hand. Though the raid time was earlier than when Studio 54 employees normally clocked in, somebody – probably a “cleaning man,” according to Sudler – was there to open up. “We tried to conduct the search at the best possible time: when it was closed and nobody was there,” said Sudler. “We wanted to not go in there with a disco scene going on.”

Whatever the case, he added, efficiency was of the essence: “We had to move quickly. If you can’t get the evidence, you don’t have a case.” Soon after agents made their way inside, employee Scott Nilsson arrived for his shift. He usually worked

nights, manning a spot inside the front of the club, where patrons not lucky enough to be on the guest list – which had a pecking order, with those notated as NFU (No Fuck Ups) at the top – paid their admissions. But, on that day, he was there to help out in the office. An occasional job responsibility of his was counting cash from the previous night. Nilsson got to the club right after the raid began and, along with a dozen or so other employees, was told to wait outside.

“I was shocked and not shocked,” Nilsson said. “Steve had been talking about how much money Studio was making. And, if anything, I thought they might have been laundering money.” Rubell told finance columnist Dan Dorfman, in the fall of 1977, “The profits [are] astronomical. Only the mafia does it better.” That was a jaw-dropping statement for several reasons. First, Schrager’s father had the kind of mob ties that earned him a mafia nickname: Max the Jew. Second, he and Rubell were cooking the books in a style that was at least a little bit mafia-esque. What’s more, they were not exactly keeping it a secret. When the reporter, Dorfman, asked about revenues, Rubell replied, “It’s a cash business and you have to worry about the IRS. I don’t want them to know everything.” Clearly, someone with connections to the IRS was reading. Employees did not need to be insiders to know what was going on.

“I knew they were exchanging the tapes,” Nilsson said, referring to tapes that tracked how much money went in and out of a given cash register. At some point in the night, said Nilsson, “They would close the register and pull out the money. The first set of tapes was reported and the second set was not.”

From Nilsson’s vantage point, things looked dicey, as feds rolled out boxes of records, file cabinets, and books. Standing with other employees, Nilsson wondered whether or not the club would open and could only speculate on what was going down inside. One person who knew was Ian Schrager. He showed up for his day at the office and was surely shocked to see his nocturnal gold mine being raided. Schrager could have done a lot of things at that point but, by strolling into the scene of a raid, he opted for one of the dumbest.

“I thought it was unusual that he would walk down the street, see IRS people searching [his place of business] and walk inside,” said Sudler. “I thought it was incredibly stupid.”

With the warrant that the authorities had, anything he brought in from the outside was privy to being searched. Inside a briefcase being carried by Schrager, authorities found five envelopes. Each one contained an ounce of cocaine. The coke was nearly pure. Schrager was arraigned on a complaint of possessing cocaine with intent to distribute. He was sent home after putting up a $50,000 bond, but the white powder was nothing compared to what agents found in the ceiling. As explained in the documentary, Studio 54, records literally pointed out that money was being skimmed because they contained a column with the word “skim.” According to charges, more than $3 million in cash was ultimately seized from inside the ceiling of Studio 54, from a Citibank safe deposit box and from individual home safes.

“We found manila envelopes as evidence of a skimming operation,” said Sudler. “They had one for every day. You could see an enormous amount of money not reported. I was surprised at the amount. It was almost 80 percent. Typically, you don’t skim that much.” The situation for Schrager and Rubell got even worse when investment partner Jack Dushey copped a plea. It’s been characterized as a willingness to shoulder blame. Sudler, however, does not see it that way. “He did not take the rap,” said Sudler. “He pled guilty to a felony and testified. In exchange for his testimony, he was granted leniency. He

gave it all up. He put a voice on the records.” Lawyer Roy Cohn – the shrewdest, smartest, most well-connected counsel out there in the late 1970s – and a phalanx of other attorneys worked overtime to resolve problems of Rubell and Schrager. They created legal smoke and mirrors and a blizzard of media. There was even a ham-handed attempt to seek a break by maintaining that the club owners could provide information about Hamilton Jordan, then President Jimmy Carter’s White House Chief of Staff, snorting coke at the club. That gambit backfired and even may have brought enmity from the White House. Bad move.

Still, you’d never have known it from how Rubell and Schrager visibly handled the stress. Multiple sources make it clear that they moved forward as if nothing was amiss. The club went through a major renovation – with augmentations to make it competitive against a newly opened Studio-wannabe disco called Xenon, including a moving bridge inspired by the Broadway play Sweeney Todd. Additionally, new businesses were in the offing.

Schrager was deep in research mode for a designer jeans line – examining bestsellers from Bloomingdale’s and Fiorucci for ideas that could be co-opted. There was talk of a record label and Benecke looked at a space across the street from the Beverly Wilshire Hotel for a proposed Los Angeles offshoot of Studio 54. None of that was to be. By February 1980, avenues of defense and opportunities for resolution were exhausted. Saturday Night Live even parodied their problems, with John Belushi playing a coked-up Rubell.

Meanwhile, enemies of the two partners were gloating. Rubell and Schrager copped a plea. They were sentenced to four years apiece, on two counts of income tax evasion, charged with skimming $2.5 million and defrauding the government of some $400,000. Before they left to do their time, though, there was a last blast in the club that they made famous. “My Way” played on the sound system and at least one booster showed up with a tee shirt that read “Free Steve Rubell.” Drugs flowed, the dance floor bumped, Liza Minelli and Diana Ross sang them off from the moveable bridge. Word has it that Ross lost a shoe there that night. Of course,

Studio 54’s employees – many of whom soldiered on with their bosses behind bars – lost something much more. “We loved Steve and Ian,” said Myra Scheer. “It was like Mom and Dad [were leaving]. Freddie, who was Steve’s bodyguard, summed it up best. He said, ‘If there was any way I could go to jail with him, I would.’” The partners were remanded to the Manhattan Correctional Center. Knowing, perhaps, what a couple of pampered New Yorkers would be missing most while behind bars, Sudler took a last shot at gaining some form of cooperation from the partners. “We were investigating other discotheques,” recalled Sudler when being interviewed on the TV show Building NY: NY Stories with Michael Stoler. He arranged a sitdown with Rubell and Schrager – and had it strategically catered. “I ordered a slew of Chinese food,” he revealed. As the scent wafted, “Rubell looked around and asked for some of the food. I said that they had to be part of the team [if they wanted to eat].” By all indications, Rubell and Schrager dined well that night. In the documentary, Schrager insisted, “It isn’t as if we named names. But we would have perjured ourselves if we didn’t answer question about [the other] nightclub owners… They were our enemies.”

Rubell and Schrager did their time, got out of jail and transcended their initial success by getting into the hotel business. Following the Studio 54 model – transforming a rundown and abandoned space and making it something mind-blowingly special – they purchased a decrepit West 46th Street and Eighth Avenue dump called the Paramount. The spot was an instant hit that launched their company and transformed the hotel industry, making the overnight business as cool as the nightclub business. Things were booming in 1989 when Rubell died from hepatitis and septic shock complicated by AIDS. He had been closeted for much of his life, so much so that he told reporter Dorfman a tall tale about an ex-girlfriend breaking up with him over his workaholic ways. Schrager, meanwhile, thrived as hotelier to the fashionable, with properties that have included the Royalton, Mondrian, and Gramercy Park Hotels. He currently heads up the chic Public Hotels brand.

In 2017, then President Barack Obama pardoned him for his crimes. The process was helped along through a letter written by the man who put him behind bars, Sudler.

“Schrager called and told me he wanted to apply for a pardon,” Sudler told Stoler. “[Schrager] said it’s because he has five children and he wants the pardon so they know he is not just a convicted felon. I wrote a letter based on him having done his time, become a big hotel-success, paid his fine [of $20,000], cooperated.”

Looking back on it all, Myra Scheer can’t help but wonder if everything wound up for the best: “Look at what Steve and Ian did after Studio 54. After getting out of jail, they went way beyond the nightclub business. Studio was just the start.”