Rap and R&B power couple Kasseem Dean, known professionally as Swizz Beatz, and Alicia Keys are noted collectors of sound systems, BMX bikes, Grammys, and Recording Industry Association of America certifications. The superproducer, who has made hits for Beyoncé, Jay-Z, DMX, and Drake, and the chart-topping singer-songwriter own speaker columns that once belonged to Kool Herc, vintage Dynos in every color of the rainbow, 16 gilded gramophones, and countless framed platinum records between them. But over the past 25 years, the Bronx- and Manhattan-born musicians have also quietly assembled the Dean Collection, one of the world’s most important collections of contemporary art by African and African diasporic artists. For the first time ever, a selection of over 100 of these works by 38 artists including Jean-Michel Basquiat, Kehinde Wiley, Amy Sherald, and Nick Cave—plus some of the Deans’ other collectibles—is on view to the public at the Brooklyn Museum through July 7 in an exhibition titled “Giants: Art from the Dean Collection of Swizz Beatz and Alicia Keys.”

“One of the most important things that we’ll talk about is ‘by the artists, for the artists, with the people.’” —Alicia Keys

While private collectors often loan a piece or two to museum surveys, it’s quite unusual to see a thematic exhibition on the scale of “Giants” featuring works borrowed from a single family. There’s a certain voyeuristic frisson upon entering the show in the museum’s Great Hall where you’ll find a number of pictures culled from the walls of Razor House, the Deans’ art-filled modernist home high above the cliffs of La Jolla, California, that may have served as inspiration for Tony Stark’s residence in the Iron Man films. “They want to have beautiful things in their home that represent their culture, but they very much see themselves as stewards of the work and recognize that it’s so important to have objects that are part of the Dean Collection out in the world,” says Kimberli Gant, curator of modern and contemporary art at the Brooklyn Museum. Or as Keys puts it in the exhibition intro, “One of the most important things that we’ll talk about is ‘by the artists, for the artists, with the people.’”

The newly blank walls at Razor House include two in the trophy property’s piano room behind and opposite the Steinway Baby Grand that Keys received as a gift from her record label when she was first signed as a teenager. These were previously occupied by Paris Apartment, a vibrant charcoal portrait in which Toyin Ojih Odutola captures the luminosity of Black skin through meticulously layered marks, and a majestic figurative collage of African artifacts, sheet music, book pages, and plants by Radcliffe Bailey titled Conductor. The scale of many of the works on loan is massive. There’s a 7’9” tall Nick Cave Soundsuit fashioned from buttons and bugle beads and Derrick Adams’ Floater 74, an ebullient 25-foot long polyptych featuring Black swimmers on flamingo floats that ordinarily fills an entire wall in Razor House’s formal dining room and family room across from panoramic windows looking out on an infinity pool and the Pacific.

Giants offers is an opportunity to entice new visitors to the Brooklyn Museum. “Maybe they’re just here because they’re very curious about what the Deans have on their walls and they wouldn’t know Barkley L. Hendricks from Tschabalala Self, or maybe they kind of know of Amy Sherald because they heard that she did Madame Obama’s portrait but aren’t aware that she does these other paintings celebrating dirt bike culture,” Gant says. Once they’re through the door, it’s a chance to offer a kind of Black Art History 101 tracing a lineage of visionary artists from the mid-twentieth century to the present.

The exhibition title speaks to the colossal size of the Dean Collection itself—it now comprises more than 1,000 pieces—as well as the Deans’ philosophy of collecting. “‘Giants’ is so important because the artists are giants and the works that [visitors are] going to see are giant oversized works on purpose,” Swizz Beatz says. “When they come in here they say, painted something so amazing and at this magnitude.” To underscore that point, the word “giants” is repeated in each of the three section names.

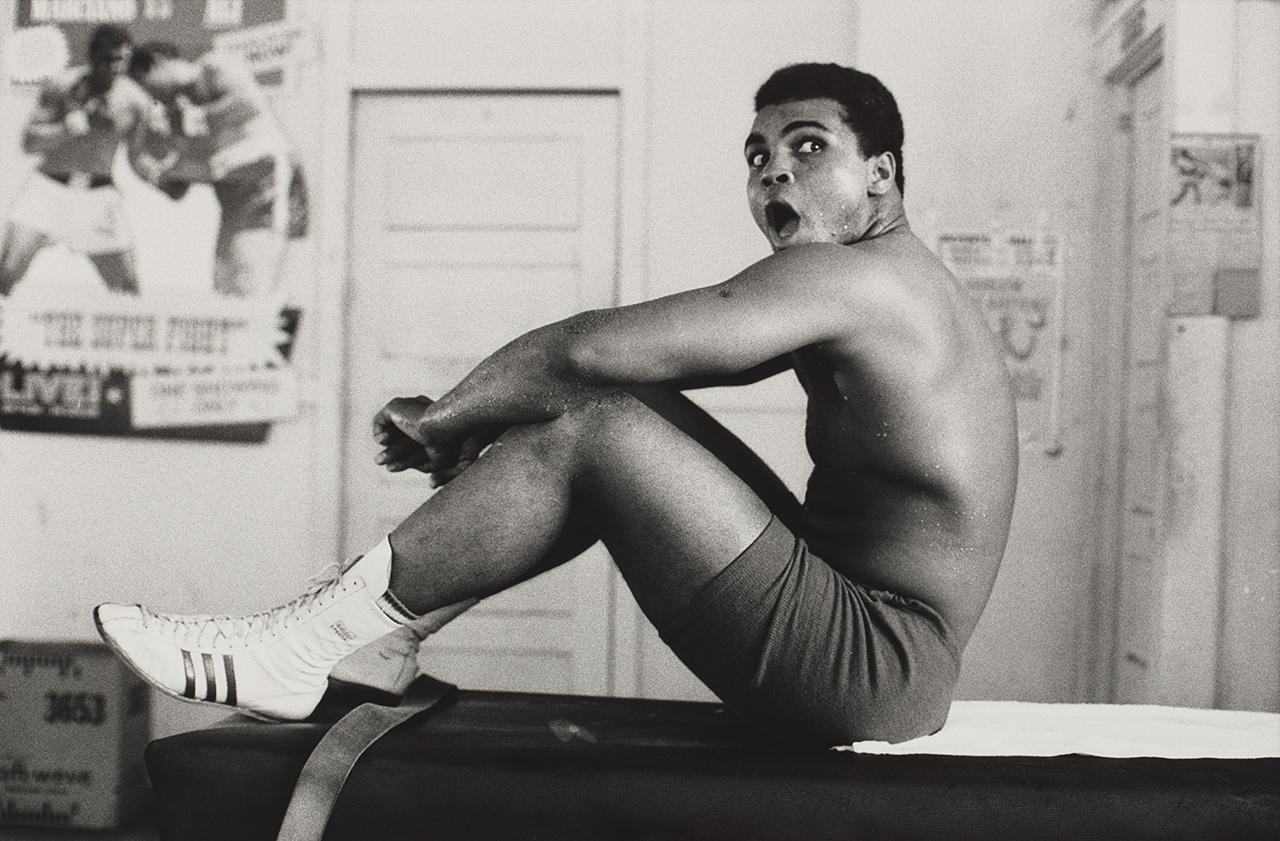

The first, On the Shoulders of Giants, honors path-breaking artists like Basquiat, Malick Sidibé, and Lorna Simpson whose work celebrates Black self-presentation and pride. Works on view include 12 prints by street-style pioneer Jamel Shabazz, who photographed stylish denizens of pre-gentrified Brooklyn while working a day job as a corrections officer in the 1980s, and 18 from the estate of Life magazine’s first Black staff photographer, Gordon Parks, including portraits of Civil Rights leaders and boxing champion Muhammad Ali.

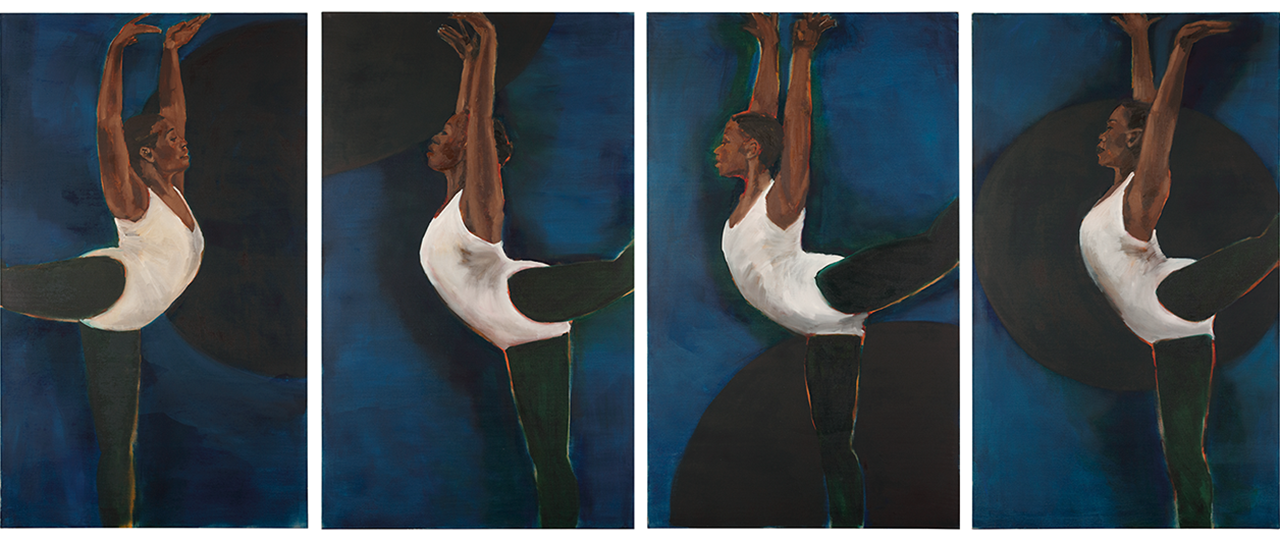

Next, Giant Conversations looks at the impact of canon-expanding contemporary art that calls out systemic racism and celebrates Blackness. This section juxtaposes charged works that address police brutality and the prison-industrial complex with pieces that celebrate Black joy and leisure. Here, Cave’s Soundsuit—a sort of fantastical protective shield that masks a person’s racial identity—is placed directly in front of Adams’ monumental Floater 74 claiming space for community, connection, and everyday pleasure. Nearby there’s another multi-panel work, Lynette Yiadom-Boakye’s Stone Arabesque, a gorgeous character study of a Black ballerina.

The last room, Giant Presence, features even bigger works, including Arthur Jafa’s 8-foot-tall tire sculpture Big Wheel and Wiley’s 25-foot-long canvas Femme piquée par un serpent recontextualizing a 19th-century marble sculpture by Auguste Clésinger of a violently contorted nude among a bed of flowers as a young Black man.

“‘Giants’ is so important because the artists are giants and the works that [visitors are] going to see are giant oversized works on purpose.” —Swizz Beatz

The exhibition opens with an introduction to Dean and Keys’ creative lives, and features new portraits of the couple by Wiley as well as an Adams diptych, Man and Woman in Greyscale, that the museum commissioned in 2017 when the couple was honored at the annual Brooklyn Artists Ball fundraiser.

The exhibition design is structured to give visitors the experience of living with these works as the Deans do. Bang & Olufsen speakers pipe a chill Marvin Gaye playlist throughout the show, there are rich jewel tone accent walls, and in place of typical wood museum benches, cozy seating areas feature plush sofas and armchairs in neutral tones from CB2’s Black in Design Collective. “I want to remind our visitors that you don’t have to only see great works of art in a museum and gallery,” says Gant. “You can buy work that you love and have it in your home and be with it every day and enjoy it and share it with friends and family.” Even if it’s just a print, poster, or postcard from the museum gift shop.