Today is Cher’s 75th birthday, and I feel pretty confident in saying that most film and culture obsessives would advise anyone wanting to mark the occasion to watch Moonstruck or Mask or Silkwood. Those more inclined toward kitsch will probably queue up Burlesque or Mama Mia! There Cher Goes This Time. But personally, my touchstone Cher performances is in 1987’s The Witches of Eastwick.

Loosely based on John Updike’s 1984 novel — and directed by George Miller of Mad Max: Fury Road fame — the film concerns a trio of single women whose magical powers blossom upon the arrival of an eccentric millionaire in their small New England town. I can’t remember the first time I saw The Witches of Eastwick, but it must have been sometime in the late ’90s during my regrettable post-The Craft, high school wiccan phase. I seem to remember renting it from the library in my own small coastal town. I remember being a little disappointed that there weren’t more actual spells and incantation, more literal magic. I came away unsatisfied with the whole thing, unsure how I was supposed to understand the film’s version of witchcraft — my primary interest at the time — unsure whether Daryl Van Horne (Jack Nicholson) was supposed to be the actual devil, or if any of that was even the point. (It’s not.)

I discovered Updike’s (admittedly super problematic) novel, from which only the most basic plot outline was lifted for the film, in college. But it wasn’t until I re-read it in my late 20s that I really connected with the story, and consequently the film. This was 2009. Updike had published a sequel, The Widows of Eastwick, which I enjoyed enough to revisit the earlier book. And this time it spoke to me: its sardonic nastiness, its misanthropy, its melancholy. The following summer, I found myself under-employed and spending most of my time on Fire Island — yet another cloistered seaside community in which sex and gossip and bitchiness were currency. During the day, I would wander the shady boardwalks listening to the audiobook. Late at night, I would crawl into bed and fall asleep re-watching the film. I would imagine every hot tub party as a witches’ sabbath.

I became fixated on the idea of witchcraft as arising from, as Erica Jong put it, “powerlessness and its concomitant frustration.” At that time, in that privileged milieu of impossibly sculpted bods and absurdly inflated bank accounts, I did see myself as somewhat powerless. Coming up short in both looks and finances, I liked the idea that one’s wit and wisdom could conjure what one wanted. And if that failed, there was a certain comfort in the shared spite of the coven; in, as Updike writes in Widows, the “collusion of rebellion against the oppressions of respectability.”

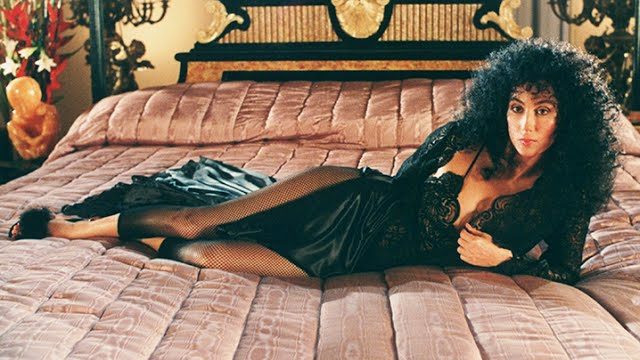

So, what does any of this have to do with Cher? Well, in the film version of The Witches of Eastwick, she plays the witch with whom I most closely identified. Alex (Lexa in the novel) is inarguably the queen of the coven. She’s the witch to whom both Jane (Susan Sarandon) and Suki (Michelle Pfeiffer) defer, the one they turn to when things with Daryl sour. And it’s obvious why. Even in laughably voluminous pigtails, she’s a steely, statuesque presence. She’s Cher, for Christ’s sake!

Last year, Sarandon made headlines when she revealed that she was originally cast as Alexandra, and implied that Cher may have used her feminine wiles to convince one of the film’s producers to swap their roles. Obviously, both actors are world-class talents, but it’s hard to imagine Cher in the role of mousy music teacher turned frivolous vixen given the steady, unflappable power and presence she brings to her performance as Alexandra.

But, if I’m honest, there’s a lot of metatextual work I’m doing when I watch Cher in The Witches of Eastwick. I’m bringing a lot of the kinship I feel with Updike’s version of Alexandra to the film. As is so often the case when men write about groups of women, Updike’s witches represent types: Suki the sex kitten, Jane the antisocial bitch, Lexa the nurturing earth mother. But of the three, Lexa is the most fully drawn. Though the novel switches perspectives, she is the character in whose head we spend the most time. She struggles with depression and insecurity and body image, and it’s from her perspective that we get some of the book’s most resonant insight. Suddenly aware of the inexorability of her depression, she has the sensation that “her life had been built on sand and she knew that everything she saw tonight was going to strike her as sad.”

In another passage, Updike writes of Lexa, as she approaches Daryl Van Horne’s mansion: “Her heart lifted into its holiday flutter, always, coming here, night or day, she expected to meet the momentous someone who was, she realized, herself, herself unadorned and untrammelled, forgiven and nude, erect and perfect in weight and open to any courteous offer: the beautiful stranger, her secret self.”

Decades later, in Widows, she remembers those gatherings with Suki and Jane and Daryl: “Every night was a party night whose opportunities might crack open the jammed combination-lock of her life.” I’m not sure I’ve ever encountered anything that distilled so perfectly what it felt like to be a gay boy in my late 20s and early 30s, going out to bars and parties every night in search of who knew what.

All of this is what I’m thinking of when I think of Cher in The Witches of Eastwick. (And then of course, there’s her fantastic dressing down of Daryl in the film!) At 75, she is more or less the same age as her character is in The Widows of Eastwick. If she’s not feeling too raw about Sarandon’s comments, maybe it’s time to get the coven back together for a sequel.