The East End, the tidy moniker given to the far end of Long Island, NY, is somewhat of an oxymoron. Spotless beaches entertain both unwieldy mansions of the wealthiest of the wealthy, and quaint villages whose denizens count the days until fall when housewives pack up and head back to the city. It’s hard to imagine a time when the placid potato fields stretching from NYC to Montauk were relatively secluded.

This isolation, combined with the magical light and pristine views of the Atlantic, drew an unlikely group of artistic explorers around the middle of the last century. Arriving somewhat grimy from cold water flats in downtown Manhattan, they came armed with canvases and hoping for inspiration. Today, we know their names, at least some of them. The male sect would secure their legacy and cement their output as the de facto brand of American art; their equally talented female contemporaries, less so. The story is old. And tired.

In the past 10 years, much has been done to confront this bifurcated body politic. Beginning with a few small gallery owners—often women themselves, like Anita Shapolsky and Katharina Rich Perlow—who recognized the merits in this fertile body of untouched treasure, the women behind these lionized men began to have their stories uncovered. In 2016, the Denver Art Museum mounted Women of Abstract Expressionism, and while it wasn’t the first museum show of its kind, it rang out loud and clear. Recently the Parrish Museum in Watermill has launched a landmark exhibition, Affinities for Abstraction: Women Artists on Eastern Long Island, covering 42 artists “who have called the Hamptons home for a week, a season, or a lifetime.” It’s open through the summer and highly recommended.

While female artists of the past are now more present than ever in the exclusive world of art, many of their names are still not nearly as recognizable to the general public as they should be. For every Pollock or Warhol taught to school children, they should learn of people like Anne Ryan and Sonia Sekula.

If this article were ten times as long it would still not scratch the surface of all names that should be mentioned. By a long shot, this list is woefully short. It is also not lost on me that many of these women came from privileged upbringings, and all were white. While the art world can seem like a very liberated space, there is still a mountain of work to be done.

But, as Leonard Cohen said, “there are heroes in the seaweed.” We just have to keep looking. For the sake of brevity, here are some of my favorites.

MARY ABBOTT

One of a few female artists to be included in The Club, the fabled “salon” frequented by New York’s most important artists, writers, musicians, and thinkers, Mary Abbott’s intuitive abstract paintings have a transformational quality, saturated with an energy that seems to channel, if not actually capture, vibrant landscapes, flora, or simply the changing light of day.

A descendant of President John Adams, Abbott grew up in New York City and frequently spent time in Southampton, where she would eventually reside permanently. As a member of the social elite, she graced the covers of no less than Vogue, Harper’s Bazaar, and Glamour. This however, would become a minor footnote in her remarkable career.

While studying at Rothko and Motherwell’s Subjects of the Artist School, an unconventional, short-lived “anti school,” she experimented with the hallucinogenic peyote, which opened up her understanding of color and allowed her to better harness her use of it. In a video from the Denver Art Museum exhibition Abbott stated “Trying to do things representationally didn’t work for me. [With abstraction] I could talk in a different way.”

To view Abbott’s paintings is to view that intense grip of color. Annual trips to Haiti and the Virgin Islands greatly influenced her work, and it is in her swaths of pinks, greens, reds, and golds that we are transported to these tropical landscapes. Her most exciting works though, are her works on paper. Vaguely representational forms are suggested smartly by a quick line of black, or constricted into tight balls of vibrating chromatic energy eager to explode. No brushstroke or crayon mark is unnecessary or used carelessly.

It is rumored that her abstract landscapes influenced similar works by her male counterparts. It is rumored that she had an affair with fellow artist Willem de Kooning. What is empirically true though, is that Abbott’s works represent the pinnacle of Abstract Expressionism.

Why she is not better known on a greater scale, even among her female counterparts, is a puzzling question. I knew Mary and I can tell you, she was a firecracker you wouldn’t quickly dismiss. Once, while discussing another artist (who was, in fact, a friend of hers), Mary insisted that her slight French accent was an affect. I innocently pointed out that the artist was indeed born in France. She replied caustically out of the side of her mouth, “Yeah, but not the right part.”

CHARLOTTE PARK

Neighbors of Jackson Pollock and Lee Krasner in New York City, Charlotte Park and her painter husband followed the conspicuous couple out to Long Island. Despite being firmly ensconced in the often rowdy crowd of the Cedar Club, the couple is often described as being relatively temperate and collected.

Until recently Park was little known, having kept a low profile while her husband’s career was nurtured. Despite gallery shows and inclusion in annuals at the Whitney Museum throughout the 1950s, Park was mostly absent through the 1960s.

Park’s work itself may be the key to unlocking the quiet nature of her career. Perhaps she did not have to say much because her work speaks so strongly for itself. Her early paintings, largely in black and white, are undeniably assured, rich with paint, leaving no space unconsidered. While not aggressive, they exude the strength with which artists like Franz Kline are typically hailed. Unlike Kline, there is a very sensual tumult brooding in her works. These works are not rigid. These works are breathing.

A museum-quality painting at Berry Campbell Gallery, titled Departure (c.1955), introduces color to her composition in a fearless way. Ochre, deep orange, and an oddly contrasting sky blue co-exist in a united huddled mass. Her agility working with such disparate hues gives the painting a feeling of community. Gallery owner Martha Campbell says of the work, “I can say without a doubt that she was one of the most naturally gifted painters I’ve ever seen. In Departure, her surfaces are worked, scraped, and then built up again, this process repeated countless times, each layer adding new energy and each scrape revealing more brilliant color combinations. The end result is this sparkling energy, each component magnifying and complimenting that of the previous.”

To say that Charlotte Park’s work is underrated is to say that the dictionary is a book that has some words in it. It is sad to note that, to date, at auction, her record high is a mere $11,000. I cannot imagine that number will hold steady for long. Increasingly top galleries like Campbell’s have taken note and museums have followed. Park’s work is now showing up at art fairs with regularity.

Campbell Gallery, New York

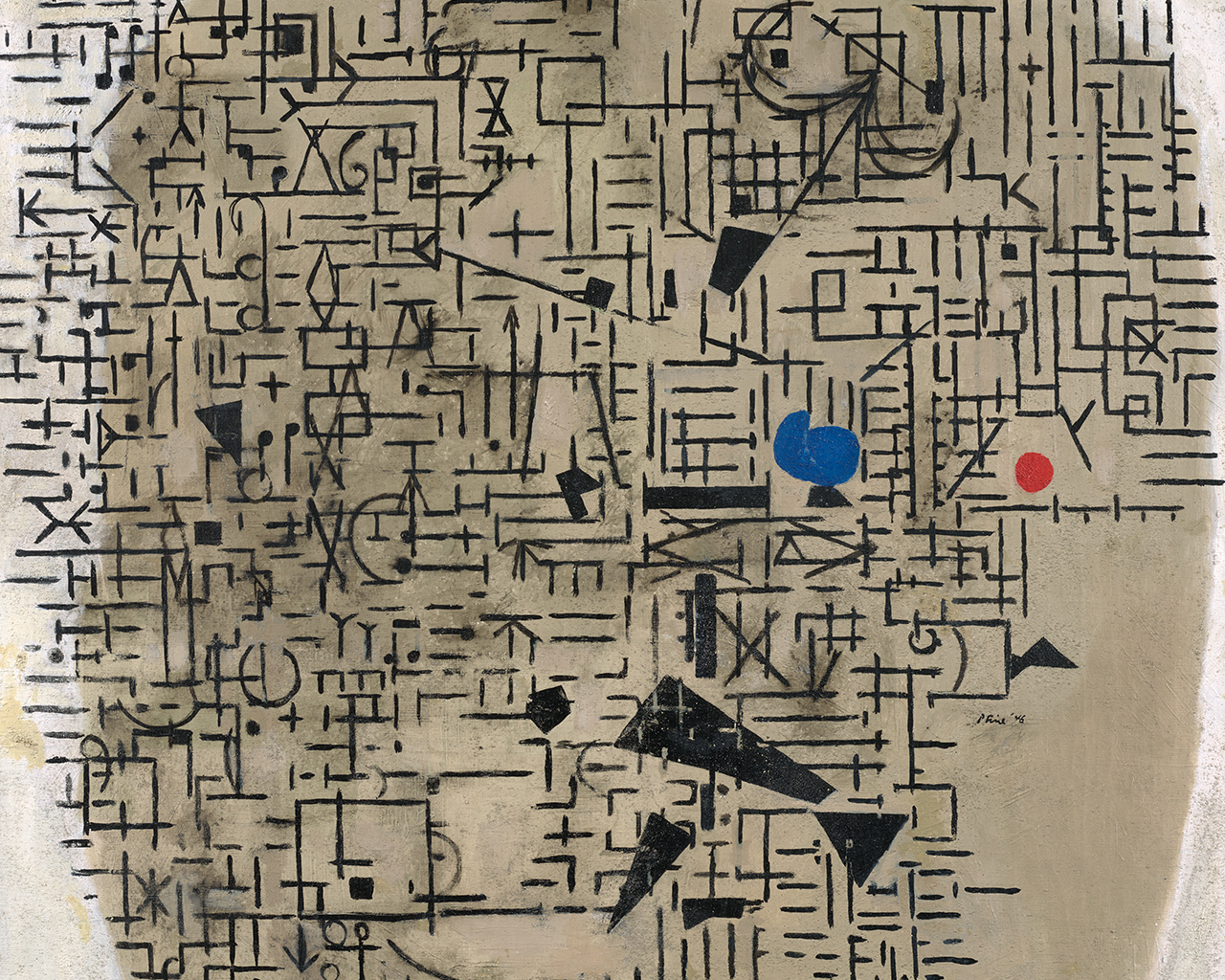

PERLE FINE

A quote from artist Perle Fine from 1976 might best underscore her obvious dexterity and confidence. “When I paint something I am very much aware of the future. If I feel something will not stand up 40 years from now, I am not interested in doing that kind of thing.” Trust me, these works stand up!

Fine was one of only a few women promoted by Hilla Rebay and the Guggenheim Museum in the 1940s. In 1954, she left the political trappings of New York City and built a one-room studio in the Springs section of East Hampton, where she would live and work for the rest of her life.

Her body of work is truly fascinating. Despite changing methods, materials, and ever-evolving styles—gestural works in the 50s, color field in the 60s, Op and minimalism in the 70s—Fine was a staunch advocate for abstraction as a framework and color as expression. Reviews glowingly speak of her ability to achieve harmony and to evoke feeling through her precise visual rhythms.

Throughout every period of her life, Fine exemplified the unyielding, pioneering American spirit. Finally, in 1978, Fine was given a retrospective at Guild Hall in East Hampton titled Perle Fine: Major Works 1954-1978. I would say it’s time for another.

MERCEDES MATTER

It would be all too easy to summarize Mercedes Matter’s legacy into a story of scandal and beneficence. She has been properly celebrated for her contribution as a beloved educator and mentor. After writing an article in Art News in 1963 titled “What’s Wrong with U.S. Art Schools?” she was pressed into action by her students who, like her, were disenchanted with the antiquated and academic art instruction offered. In response she founded The New York Studio School, housed in the former Whitney Museum building in Greenwich Village. Gagosian Quarterly did a marvelous homage to Matter in their fall 2020 issue.

But what about scandal? I could talk about the intimate relationships she fostered with some of New York’s most influential power brokers. She was known to be an incredibly striking beauty (the stunning nude photos her photographer husband Herbert Matter took of her on the beach in Provincetown in the 40s confirm this) with an even more striking and fierce intelligence. Writers have made a case for Matter’s proclivities as a proto-feminist reaction to the unbalanced gender politics of the time. Matter was ready to play like the boys. I could also talk about the cache of dubious Pollock paintings found in a family storage locker, but that would be gossipy.

Sadly, where Matter’s confidence in her intellect succeeded, her certainty as a painter was somewhat lacking. She was famously known for turning down a solo show with respected dealer Leo Castelli. This is a shame because her paintings are teeming with complexity and tantalizing duality that is far more interesting than the salacious aspects of her life. Matter’s paintings practically buzz. Despite a sometimes soft palate, her brush strokes are explosive, bursting forward with an unexpected momentum. She was known to work from still life compositions and if you strain just enough you can almost see the source material.

Heather James Fine Art, which currently has an exhibition of the artist’s work says that, “despite the spontaneous look and free nature of her abstraction, Matter would spend months or years on works, turning a sharp eye to in-person, real life studies. This dedication to life studies informed her founding of the New York Studio School where future generations of artists like Christopher Wool would get their start.”

Her friend and fellow Abstract Expressionist artist Elaine de Kooning remarked of Matter’s work, “Everything has a miraculous, alive quality.” In a painting from their exhibition, titled Still Life (1962-63), the play between subject and space is forged into a beautiful chaos.

BETTY PARSONS

Of all of the female artists whose name should be as storied as Pollock or de Kooning, perhaps no one deserves it more than Betty Parsons. This is not to say that much hasn’t been written on Parsons or that her contributions and accomplishments aren’t noted. She is capital “V” venerated within the “art world,” but it is the dichotomy of her name not being household” that is a travesty.

Like Abbott, Parsons was born to a wealthy family. At the age of 13 she visited the 1913 Armory Show, the international exhibition that introduced Americans to Modern Art with works by Brancusi, Duchamp, Kandinsky, and the like. A failed three-year marriage was followed by a Parisian expat period of serious art study, as well as dancing with Josephine Baker and Alexander Calder. In California, she is said to have played tennis and flirted with Greta Garbo. By 1936, her finances shaky from the financial quake of the Great Depression, she moved back to New York and had her first solo gallery show.

In 1946, the vanguard Betty Parsons Gallery opened up on 57th Street in Manhattan. In short, it was a cataclysmic success. At the time there was a very small market for avant-garde art. The artists she championed are today hallowed in every museum in America and abroad. Their names have become synonyms for American art – Rothko, Still, Hoffman, and yes, Pollock.

It would be easy to assume from that list that she only gave opportunities to straight, white, cisgendered men. But she didn’t. Parsons showed women like Louise Nevelson and Agnes Martin. She showed Black, Asian, and Latinx artists such as Thomas Sills, Kenzo Okada, and Roberto Matta. LGBT artists such as Sonia Sekula, Alfonso Ossorio, and Ellsworth Kelly were also represented (it has been suggested that Parsons herself was relaxed on the sexual spectrum). My personal favorite? Forrest Bess (they/them), whose mystical, visionary paintings chart a visual path of exploration of subversive sexuality and gender.

If her career had been encompassed solely by the last two paragraphs, that alone should make her a “household” name, ripe for a Cate Blanchett biopic. It isn’t, and that is also only half the story. Parsons was an incredibly accomplished artist in her own right. Her works have an easy, naive quality that in many ways counters the often overly complex works of her artists.

In 2020, Parsons was the subject of two illuminating solo shows at Alexander Gray Associates. In her works, amorphous forms are laid out in playful compositions, dancing around the plane, sometimes suggesting topography, sometimes anatomy. Her palette is unique, especially considering what was de rigueur when these were painted. Parsons clearly liked color and was unafraid to try every crayon in the box. There is no fussy blending of colors. Each is kept relatively unmolested and applied with a very even hand, which makes the paintings clean and clear. If you walked into the Alexander Gray shows, and didn’t know better, you could easily assume that these were the work of Brooklyn’s or Berlin’s next great discovery. I haven’t even mentioned her wood constructions culled from beach debris on the Long Island Sound that are quickly rising in price, thanks to their growing presence at auctions like Rago, Sotheby’s, and Christies. I’d happily make space for one, or ten. 1977, Parsons coined the phrase “invisible presence” to describe the energy she experienced in any given setting, an energy that she attempted to capture in all forms of her artwork. The paintings leave open a lot of space for interpretation, and it is that ambiguity that most works to her advantage. Despite the success of her eponymous gallery, Parsons was an intensely private woman. Betty Parsons’ paintings make you want to know who Betty Parsons really was.