Rise Above Dove (2021), Dubai Design District mural, 7.5x15m

For American street artist and activist Shepard Fairey, a blank wall is an invitation. “I love making public art. Some people would rather be on a beach; I’d rather be on a lift with a paint can in my hand,” he laughs. “I think that public art is valuable in any city. Having an opportunity to experience expression in public, rather than just blank walls or advertising or government signage, is really important when you look at the multidimensional aspects of every human. People respond to aesthetics, music, and creativity. So for there to be such a significant space, a forum, that’s lacking something that people value in a significant way, just seems to me like a void to fill.”

Such is his conviction in this idea that he spent four days on a hydraulic crane creating two 7.5x15m murals in Dubai Design District, inspired by the themes of peace, harmony and creative empowerment. “When I do these public pieces, I hope that people consider the message in that specific piece, but that it also gets them to start looking at a lot of other things differently – about how public space is used, and about the potential for art to communicate. Maybe they research more of my work and they discover all the other images and ideas in my art other than just that specific piece. It’s extremely important to me when I go anywhere to do an indoor art show that I also do public work, because democratising art is a pillar of my philosophy. Selling art is necessary, but it’s not my number one priority.”

The art show in question was Future Mosaic at Opera Gallery in DIFC – Shepard’s first exhibition in the region. “I’ve been wanting to come to the Middle East because I look at US foreign policy, and conflicts of culture globally that sometimes I think are exaggerated for the benefit of someone’s agenda, and I have my own feelings about how universal human decency is. So I’ve commented on Islamophobia, basically this compartmentalisation of the Middle East. I find it incredibly frustrating because I think it’s important to assess things on a human level and not succumb to these really lazy cultural stereotypes. Obviously, the Middle East is not monolithic – Israel is very different to Syria, which is very different to the UAE. So I wanted to see some of it first-hand for a lot of reasons: for my own perspective and my own experience, and because everywhere I travel always gives me inspiration creatively, and it allows me to meet people and hear what they’re going through.”

A detail of Rise Above Peace Fingers (2021), Dubai Design District mural, 7.5x15m

His OG street name, Obey, is itself a challenge to question authority and the status quo, so for many familiar with the connective thread of his work – from the subculture stencilling experiment that became the ‘Andre the Giant Has a Posse’ sticker sensation to the 2008 ‘Hope’ poster he created of Barack Obama as a grassroots statement that became the emblem of the future 44th US president’s election campaign – Dubai was an unexpected destination for his first exhibition of the year. “There was a lot of misdirected negativity about Dubai when I announced this project,” he acknowledges. “I think the Middle East is so misunderstood because Americans mostly don’t travel, and there are people who really benefit from stoking fear, and that’s their currency. So I think that people experiencing a place and realising that humans are humans would help.”

From his own experience of the emirate, he reflects, “I found it to be a lot more diverse, international, and tolerant than I expected. There are just so many different cultures mixing here that it’s an international city in the same way that New York or LA is.” He points out, “A place like Dubai is actually a really important bridge from the US to the Middle East. That’s really going to be one of the things I talk about when I go home, that in Dubai, you’ve got people in traditional garb who were born in the UAE, and you’ve got people from all over, but it all feels very harmonious. And if you are afraid to go somewhere like the Middle East because you feel that you won’t understand how to fit in culturally, this would be a good place to go to see that it’s not something to be afraid of.” He sighs, “It seems really crazy to me that people are so fearful. A lot of the clichés that people are told haven’t been my experience at all.”

Future Mosaic featured 157 works, many of which were produced during the Covid crisis. “‘Lotus Angel’ was one of the first images I made at the start of the pandemic,” he reveals. “I love the lotus as a symbol; it’s a beautiful flower that grows out of the mud and symbolises harmony and resilience. That was saying, ‘Hey, this is uncharted territory that we’re going into together, and we can all overcome it together’ – images that have a positive, optimistic symbolism. I did another image of a healthcare worker holding up a torch – a little bit inspired by the Statue of Liberty and Rosie the Riveter – iconic symbols of rising above or meeting challenges.”

He continues, “The theme Future Mosaic applies to the art and my approach to life – building on past ideas and frameworks, expanding on those ideas and creating something new. A lot of my work is about making people see their own vulnerability and their own humanity in everyone else. There’s hopefully an empathetic component of what I’m trying to put across. And even when I’m critiquing injustice, it’s always to say, ‘Look at the lack of humanity in this problem; let’s look at it with more humanity,’ whether that’s around climate change, or racism, sexism, xenophobia, classism… and what your response would be if you could put yourself in the other person’s shoes.”

Shepard confesses, “One thing it’s really important for me to be upfront about is that, since I hadn’t spent any time in the Middle East, the idea of how I would perfectly address aesthetic or cultural idiosyncrasies of the region just isn’t a possibility. So I tried to look broadly at what the principles and aesthetics in my work are that I think work for humanity. And then what are some of the things that I’ve been inspired by from the Middle East that tie into some of this work? With a lot of the patterning that’s in the tile work and that also was part of the inspiration for the title – because there’s a lot of really beautiful mosaic work in different parts of the Middle East – I looked at how the aesthetics of a lot of the pieces I was making would at least crossover.”

He elaborates, “The title, Future Mosaic, encouraged the audience, rather than thinking selfishly in the present, to think generously with an eye on the future. And when you looked at all the works in the show, there were images that I think are pretty universal, but not catering specifically to Dubai – because I didn’t know exactly how to do that anyway – but they were putting across ideas and principles that are important to me in a way that I hoped was universal enough to connect in Dubai. I try to understand the culture and the language in a way that allows me to be sensitive, but I rarely change the content or the message of what I’m saying. I might change some aspect of the delivery of that message slightly to be more in tune with a place, but since I don’t know exactly how to do that in Dubai, the way I met that challenge was to look at the aesthetics in the work that I think would connect with people pretty much anywhere.”

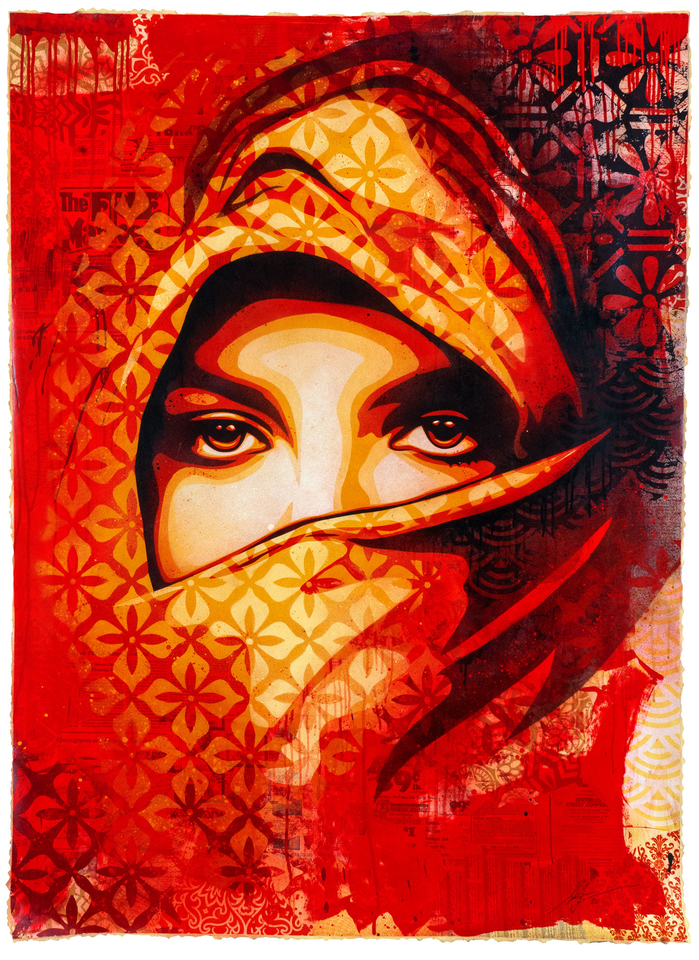

Among the most striking images in the show were his interpretations of the Arab Woman. “Context is important when I talk about those images, because in a way portraying a woman in a headscarf or a hijab in the Middle East is absolutely normal, yet very unusual in the West,” he admits. “There’s a lot of reaction just from seeing people and fearing them because they’re instantly recognised as most likely Muslim. So when I created those pieces, it was making something that tried to normalise and humanise people who had been often attacked as ‘other’. In a way, that can be seen as reductive, but sometimes portraying someone with a look in their eyes that’s undeniably relatable and sympathetic can go a long way emotionally to opening someone’s mind to ideas that they’re just like you, they just happen to wear a headscarf. I hope the audience is understanding; I’m creating them as a Westerner – a handshake from a global citizen, that’s what it’s about.”

He continues, “You can see that a lot of women portrayed in my work, and I really believe in the need for more meaningful representation for women in every facet of society, whether it’s the US or anywhere else in the world, but so many women in Dubai have told me, ‘This cliché about how women live in the shadows and are disempowered, that’s not true here.’ The sense that I’m getting is that even if there are still some ways in which women are not offered the same pay rate or the same leadership roles as men, it’s definitely not any worse from what I’ve seen than the US. That problem exists in the US, so the hypocrisy of people in the US saying, ‘If you believe in empowering women, you shouldn’t go to Dubai because that makes you a hypocrite,’ don’t know what they’re talking about.”

Shepard’s continued creative and cultural curiosity took him to Alserkal Avenue to visit the studio of fellow street artist and social commentator eL Seed. “Mehdi Ben Cheikh, the director of Galerie Itinerrance – my gallery in Paris – is Tunisian and introduced me to the work of eL Seed, and I heard he’s living in Dubai,” he reveals. “You can see the influence of Middle Eastern calligraphy on a lot of American artists also. Retna is massively influenced by a lot of Arabic calligraphy and there are a lot of great street artists in the Middle East. My friend Marwan Shahin is from Egypt, and created the sculpture of King Tut in the Guy Fawkes mask, 2Vth (aka Anonymous Pharaoh), for the Arab Spring uprising. He’s living in LA now and he did a whole poster campaign celebrating the lifting of the ban on women driving in Saudi Arabia. It’s cool to see a lot of the same ideas that I think are important in some of the street artists’ work from the Middle East. It makes me feel we’re all a lot alike, whether or not we dress the same or have the same religion, and that’s something I just fundamentally believe.”

Shepard Fairey paid Tunisian calligraffiti artist eL Seed a visit at his Alserkal Avenue studio during his Dubai trip

From his survey of the street-art scene, does Shepard think any of the talent in the region has what it takes to be considered among his peers one day? “A lot of the creative people that I’ve been talking to here say that the opportunities are just really starting to happen. It’s great that Art Dubai’s here, it’s great that there’s d3 here too, as a design – and art-focused zone to incubate that. But I think that when people think that certain visuals might not be welcome, they might censor themselves, so there need to be some steady steps from people who have the ability to share their work diplomatically, get people used to it and to have an evolution about what’s acceptable in art here. The moment that happens, it will be unstoppable. It seems to be right on the precipice,” he observes.

“I’m not an authority, but with the way it’s been explained to me is there are fears that expanding the options for expression might also be coupled with a loss of respect for other valued traditions. But then, when you try it and the true value of the traditions remain in a good way, but the conservative side starts to erode, you actually see that progress and respect can coexist – then things really start to happen,” he promises. “It only takes a few breakthroughs from people who are willing to navigate the culture, the bureaucracy and the creative world, and make it all come together.”

Rise Above Peace Fingers (2021), Dubai Design District mural, 7.5x15m