News feed

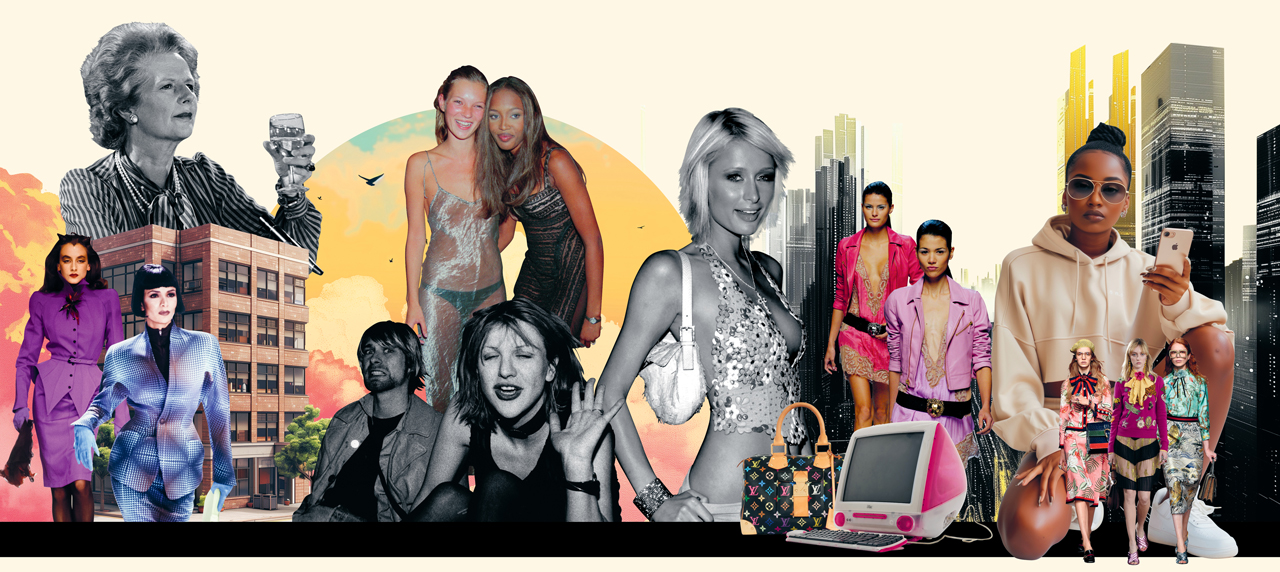

WORDS: AVA GILCHRIST ART: KIMBERLEE KESSLER

1920s

The decade was off to a roaring start on the heels of the Great War. By direct correlation, a tone of prosperity and materialism was set by the fringed flappers of the Jazz Age. A little-known French milliner named Gabrielle ‘Coco’ Chanel, influenced by the liberated intelligentsia she encountered, fashioned soft knitted jerseys into flexible day dresses that moved with ease. Sleek geometrical lines – soon to be coined ‘Art Deco’ – ricocheted over architecture, but it was the malleable and sportif shapes of gamines that had the most enduring impact.

1930s

As silent film actors found their voices, Hollywood’s Golden Age merged on-screen stars with international fashion houses, in turn creating the prototype for the ‘style icon’. This glamorous influence embraced the sultry, sinuous curves of the female form in a shift away from androgynous attire. The body was embraced rather consciously, none more so than Elsa Schiaparelli’s surrealist form, which moulded anatomical figures into objects of affection. This dreamlike sensibility contradicted the geopolitical contexts of the time. As Allied forces mobilised against Axis powers at the end of the decade, ostentation became a pervasive faux pas.

1940s

As war broke out across Europe, silhouettes were rationed with austerity, in line with conservative measures. Yet, just two years after Victory in Europe Day (VE Day), a new era for womenswear began with a singular ‘new look’. A sculpted ‘bar jacket,’ designed by French couturier Christian Dior, radicalised the sartorial restrictions of the time. The militant dress of the day inadvertently stalled progress. But after years of conflict, shortages and a focus on utility provided ammunition for designers to return to their craft with aplomb – and a fiery retaliation to the Occupation-era dress.

1950s

Like the Hanna-Barbera animations popular at the time, silhouettes became increasingly cartoonish. Expanding on the new look, shapes featured hilariously microscopic waistlines and A-line skirts. At this time, Rock’n’Roll burbled outwards from the United States’ south, leading to the hip-swinging, anti-conservative raucousness felt among youth. Teddy boys in their delinquently redefined Edwardian-era dress and rockabilly babes in poodle skirts helped create an awareness for isolated garments that amplified their social views. On a superficial level, this felt like aligning yourself with either Betty or Veronica from the Archie comics. But this concept of adhering to a code became mainstream in bourgeois beatniks and James Dean-esque greasers.

1960s

A youthquake hit as burgeoning baby boomers flew the nest in Mary Quant-designed mini-skirts and touched down in a space-age boutique on the corner of 67th and Madison Avenue. Paraphernalia was its name and it was hawked by hippies from the upstate fields of Woodstock to the streets of San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury. The counterculture emerged from the underground, preaching to the congregation through the Summer of Love in brown suede and tie-dye. In this decade, women reached new heights in stiletto heels and pillbox hats à la Jackie Kennedy. Courrèges go-go boots, Pierre Cardin’s intergalactic couture, and Yves Saint Laurent’s Mondrian Collection all captured the essence of the swinging ’60s.

1970s

Sex sold. Literally. A young Vivienne Westwood and her then-husband Malcolm McLaren opened a boutique, ‘SEX’, on London’s King’s Road. The pair peddled paperclip-punctured singlets and tattered shirts emblazoned with Westwood’s anti-establishment illustrations – it was an instant hit, especially in punk scenes, despite their hatred for ‘selling out’. Boys marched off in military green to alleviate the effects of the domino theory in Southeast Asia while drag queens threw bricks through Stonewall’s windows. A riot of liberation had begun. Old-money WASPs still wore white gloves post-Watergate until Bianca Jagger rode into Studio 54 on her ivory stallion, ushering in an era of Diane Von Furstenberg wraps and Halston ultrasuede shirt dresses. Hedonism was all the rage – in kink-inspired bondage gear, in the gold lamé of discothèques and the baby groupies of the Sunset Strip.

1980s

Reaganomics escorted a buttoned-up bourgeois attitude. Conservative politics of the time were met by equally conservative dress of blazers with protruding shoulder pads and streamlined skirt sets – the working wares of the yuppie behemoth. Across the pond and under Thatcher’s iron thumb, a materialistic culture incentivised devotion to self in power dressing and maximalist athleisure. The avant-garde musings of the Antwerp Six laid the groundwork for sartorial distress – an amalgam of creative unrest responding to a precarious climate. Thierry Mugler and Jean Paul Gaultier’s sculptural extravagance highlighted the delight of abundance. There was a flourishing of cultural capital. More was more… until it wasn’t.

1990s

Disillusionment evolved as a response to excess. The sights and sounds of teen spirit permeated the mainstream with sonic youth. Sprawled onto the streets from the Pacific Northwest in a flurry of flannel and Doc Martens, the sentiments of counterculture Seattle disrupted ideals of perpetual progress. Kurt Cobain was the patron saint of grunge. His uniform of Chuck Taylors and ripped denim became the template for a generation besotted with heroin chic. A wave of waifs saturated the zeitgeist, culminating in an optimistic Marc Jacobs marking the tides of change with a grunge collection for Perry Ellis – one influenced by the ensembles of celebrity skin. In SoHo, Sofia Coppola shot Chloë Sevigny for X-Girl’s guerrilla-style street runway. At the same time, riot grrrls articulated feminist rage in plaid school skirts and called for ‘Revolution girl style’. Valley girls and Venice skate rats aided mall culture to reach its zenith, despite Tom Ford for Gucci’s sensuality slicing through quiet minimalism. Cut the dial-up modem – the new millennium was here.

2000s

Girls of the 21st century finally burst onto the scene in McBling and Motorola Razr glamour. Blumarine Barbies wielded tabloids. They toted Louis Vuitton’s Murakami Multicolore Speedy or John Galliano for Dior saddle bags with their chihuahuas sticking out the top, up and down Rodeo Drive. The people’s princess, Paris Hilton, proclaimed “skirts should be the size of a belt!” A simple life, indeed. By mid-decade, fashion from Glastonbury and Coachella fields pervaded the mainstream with the Olsen twins, Sienna Miller and Kate Moss pioneering a bohemian redux with fur gilets and Balenciaga motorcycle bags. This rhapsody quelled after the Great Recession as manic pixie twee girls became the archetype of appeal. Down in basement bars, heads rolled to the tune of indie sleaze. A decade captured by the pixelated lens of point-and-shoot cameras.

2010s

The nascent climb of social media coincided with the proliferation of street style and streetwear. Soon, it was chic to copy listicles and the off-duty ensembles of celebrities –the latter diligently worked with stylists to meticulously curate their brand image in neutral-toned activewear. On a different dot com, collective melancholia perverted digital identities. Normcore, and in turn the idea of a generic conspicuous silhouette, entered style’s lexicon as Brooklyn’s hipster scene fell out of it. The 30-year trend cycle sprung maximalism back under fashion’s spotlight, this time in the form of Jeremy Scott for Moschino and Alessandro Michele for Gucci, who began their tenures at their respective houses and developed a visual language for eccentric bricolage and riffing on iconography. Etymology shifted to style’s new frontier, with widespread portmanteaus gaining traction in the zeitgeist. Hypebeast. Athleisure. Logomania. Viral turns-of-phrase would go on to homogenise subcultures, but the extent of labelling aesthetics would remain unseen till the 2020s.

2020s and beyond…

Where Has All The Culture Gone?

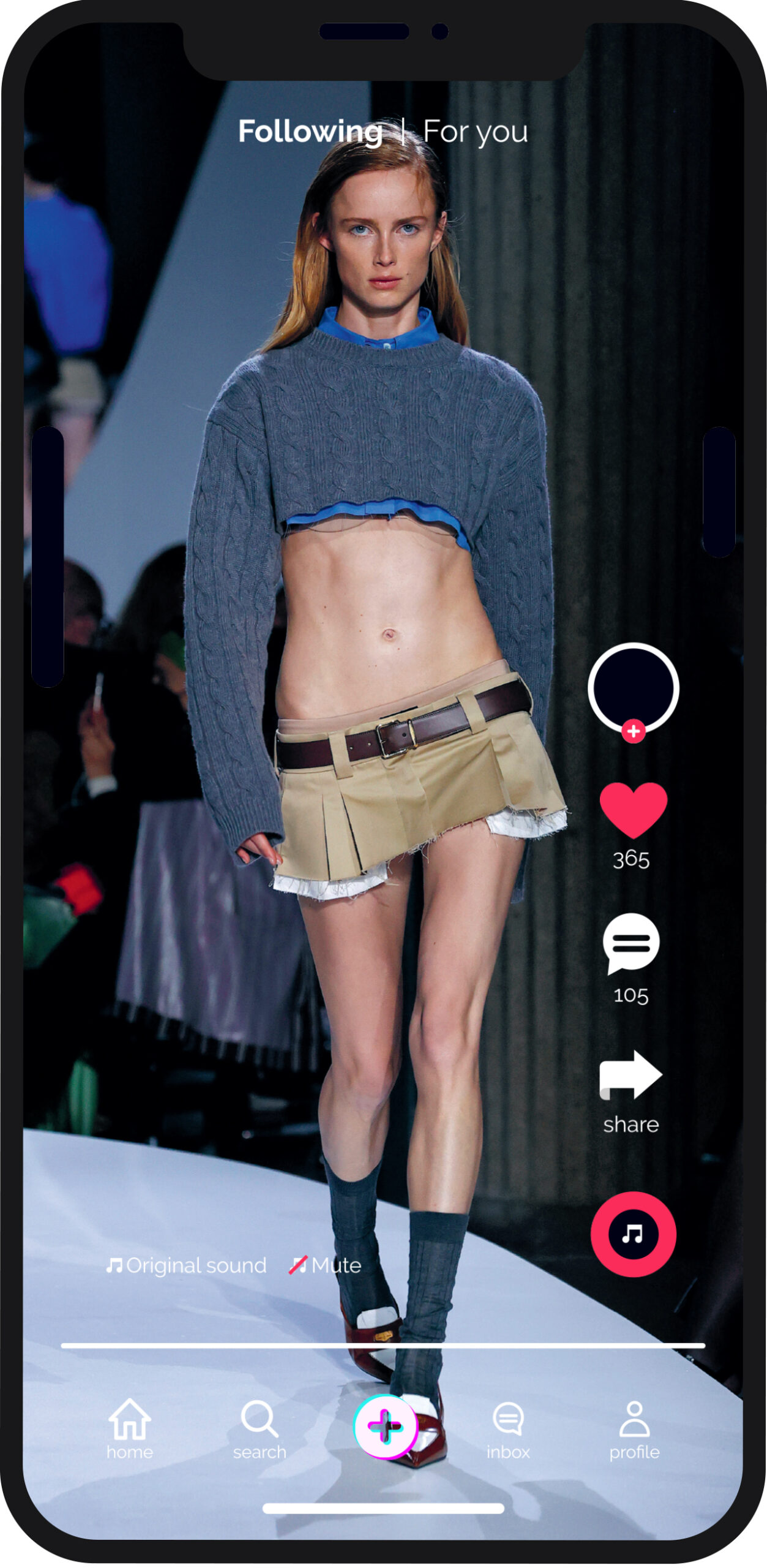

When the Covid-19 pandemic forced everyone inside and online, the gesture permanently shaped spheres of connections and culture. Where preceding decades saw ideologies made tangible through subcultures and clothing, interactions during the early years of the 2020s found a digital refuge. With copious amounts of time up our sleeves –and a soap box provided by social media platforms like TikTok – style became democratised, accessed not on the streets, but through screens. As a result, adherence to an all-encompassing aesthetic that related to your expression of the world was revoked. Instead, it was a singular style like the escapist House Of Sunny Hockney dress or the anti-utility Miu Miu mini-skirt, that dominated the zeitgeist. The fallout was clear: fashion was no longer individual, but coalesced.

Over the following years, the algorithm shifted focus from particular garments to ‘micro aesthetics’ that encompassed a slew of niche trends. (These sported garish titles like ‘Tomato Girl’ and have subsequently become mocked for their superfluousness.) As a result, an identifiable aesthetic that may have once represented a distinct group dissipated. Instead, a smorgasbord of motifs emblematic of one’s supposed authentic self became mainstream. So, where did all the culture go?

Julie Pont, the creative and fashion director of Heuritech, a French company that employs AI and social media to examine data and forecast trends, tells GRAZIA that subcultures are not necessarily disappearing, but are “multiplying and displaying more volatile behaviour”. Instead of subcultures being a conventional variant of what’s ‘mainstream’, the term now denotes a hyperspecific fad that rarely has longevity.

“We’re seeing phenomena of ‘core-isation’, which have relatively short life cycles, typically less than a year, crystallising the lifestyles of an identifiable segment.”

Scholar and fashion historian Emma McClendon agrees. Citing the ubiquity of social media in daily life, she is particularly concerned with how the platforms promote “styling practices” as having a synthesising effect on how people represent themselves.

Fleeting Feeling

As a result of this undefinable cultural dominance, a recognisable silhouette (as it is viewed in the traditional sense) is yet to emerge for our decade. Specific clothing or styling choices denoting the 2020s are being rendered out of date due to the pervasiveness of fragmented trends. Where garments or an overall uniform movement is lacking, data tells us another defining trend is emerging: repetition.

Recycling the past is by no means exclusive to the 2020s. Yet, the concept of repacking existing tropes under different labels is the biggest underscore, despite there being an increase in styles that are all seemingly unique. As TikTok’s leading fashion forecaster Mandy Lee (@oldloserinbrookyln) points out in a video touching on this exact topic: “‘Quiet luxury’ and ‘Office Siren’ are just ’90s business-casual, model-off-duty. ‘Coquette’ and ‘Balletcore’ are just late-2000s ‘manic pixie dream girl’, which is just 1960s mod and space age.”

McClendon explains that this regurgitation, or “mining of subcultures for design inspiration”, has been applicable since the 1970s. Our easy access to historical imagery has resulted in the meaning and impact of subcultural styles “appropriated into fashion and everyday dressing to such a degree that the potency is watered down,” she argues. Speaking to GRAZIA over Zoom, Lee articulated this further, explaining that the throughline of nostalgia communicates a unified apprehension for the future.

When what lies ahead looks so bleak, the rear view is more appealing than ever.

A Pixel Worth A Thousand Words

Garments have perennially been a tool for communication, signalling messages of social stratum and a personal dogma in a single stitch. In today’s digital age, the resounding message sent across the ether is one of oversaturation. Consumption in abundance is habitual and only accelerated by the quickening pace at which output is ideated, produced, labelled and absorbed. Fashion’s fleeting feeling has left a bad taste in the mouths of those who deem this expedited trajectory as trivial. But as the adage goes, ‘a picture is worth a thousand words’ – or in this case a pixel – and it’s worth thousands of dollars, too.

The act of appellation inherently imbues something with meaning and significance, and when the names bestowed on these sartorial genres read like fabrications (see: ‘Frazzled Englishwomen’ and ‘Succubus Chic’), dismissing these as trivial novelties is prevalent. However, the buzzworthy title is where the frivolity ends. Social media, micro aesthetics and hypersonic trend cycles are already stamping a lasting imprint on consumer behaviour, global economies and fashion as a marketplace.

Lee equates the ascendancy of micro aesthetics with the scarcity and commodification of time and the absence of a physical ‘third space’. (A sociological theory pertaining to a leisure-based environment.) Before the dawn of the internet, and the phrase ‘micro aesthetic’ had even been concocted, let alone entered the zeitgeist’s vocabulary, the visual codes representing a community were forged through a tangible exchange and absorption. With these interactions now taking place virtually, are they any less significant?

This is a question posited since the invention of the internet, but given the real-life impacts of micro aesthetics, we’d be quick to answer no. Fashion is no longer exclusively disseminated and absorbed in person. As our current structure not only incentivises but rewards those who lean into virality, don’t be too quick to discount this mode.

In Time

Fashion is presently in its most egalitarian state, where codes of any subculture or community are within reach and worn with risking perceptions historically ascribed to them. (Or in the case of the ‘stealth wealth’ aesthetic, it paid to be affiliated with the upward mobility and socioeconomic status associated with upper-class hallmarks.) With the speed with which we expend content showing no signs of slowing down, does this mean these short-lived, genre-specific and suffix-driven styles are doomed to be the sartorial legacy of the 2020s? This will come down to time.

“We typically need 10 years’ distance to really understand the fashion of a period,” McClendon explains. An interval isn’t the only measure. It’s also crucial what we spend time on today. Consumption of these viral trends allows people to explore facets of individualism and identity in the safest means.

“Adhering to microtrends allows participation in subcultures without having to create a whole identity. That takes time, effort, money, socialisation and vulnerability… sacred resources that people do not have!”

But as we’ve already seen, fatigue for exhaustive labelling has already begun to set in and cause people to abandon these epithets altogether. How we’ll look back at this time is ambiguous, but it won’t be without judgement, as we’ve done for all preceding eras. Ultimately, history is written by the victors. With neologisms for subcultures defined well past the decade they emerged from, perhaps our vocabulary isn’t there yet. The view of fashion’s condition is currently too microscopic, but that too will play a part in writing our legacy.

THIS FEATURE IS PUBLISHED IN THE 17TH EDITION OF GRAZIA INTERNATIONAL. ORDER YOUR COPY HERE.