Upon hip hop’s golden jubilee — the music style was born in a Bronx rec room in 1973 — the Museum at FIT, on Manhattan’s 7th Avenue, salutes the always- envelope-pushing sartorial genre it inspired with the exhibit Fresh, Fly, and Fabulous: Fifty Years of Hip Hop Style, which runs February 8 to April 23.

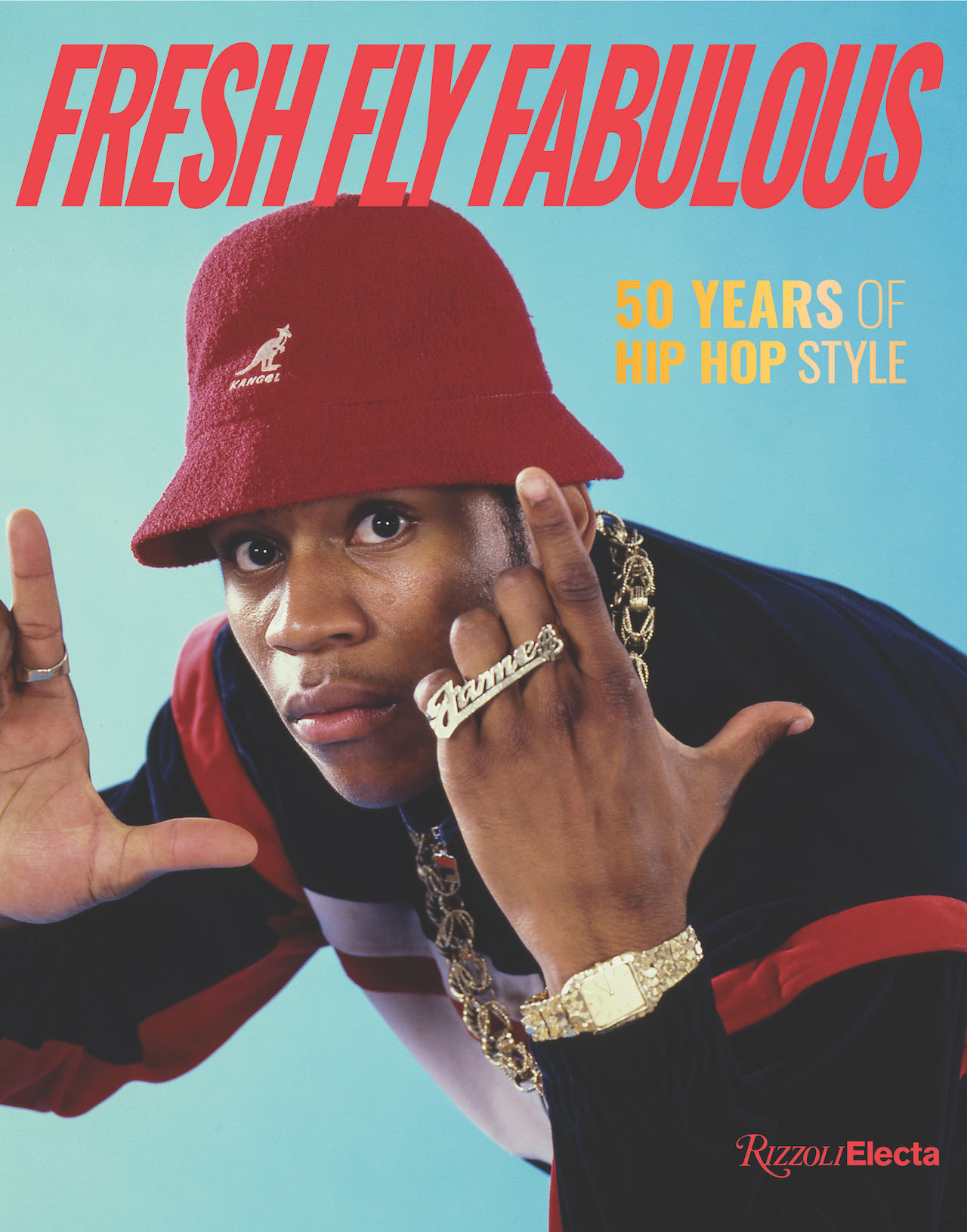

The exhibition examines the evolution of the hip hop subculture’s influence on the fashion industry via the largest and most comprehensive retrospective ever to capture the innovative style, and marks FIT’s first- ever show focused on fashion through the lens of a singular musical genre. The show even boasts an accompanying Rizzoli tome that includes a foreword from ‘80s rap legend Slick Rick, and an open-to- the-public symposium that takes place February 24.

The sweeping display by the only museum in New York City entirely dedicated to the art of fashion comes courtesy of co-curators Elizabeth Way and Elena Romero. (Way is the associate curator of the museum, and Romero has covered hip hop as a fashion journalist since the 1990s and acts as an assistant professor of Marketing Communications at FIT.)

To celebrate the now-iconic looks of five decades of hip hop, these esteemed curators started at the beginning, at that legendary 1973 Bronx party. “Kool Herc threw a ‘back-to-school jam’ with his sister Cindy on Sedgwick Avenue,” Way tells GRAZIA USA. “That’s where we start to see the DJs mixing the music and the MCs rapping over it. This is popularly recognized as the birth of hip hop.”

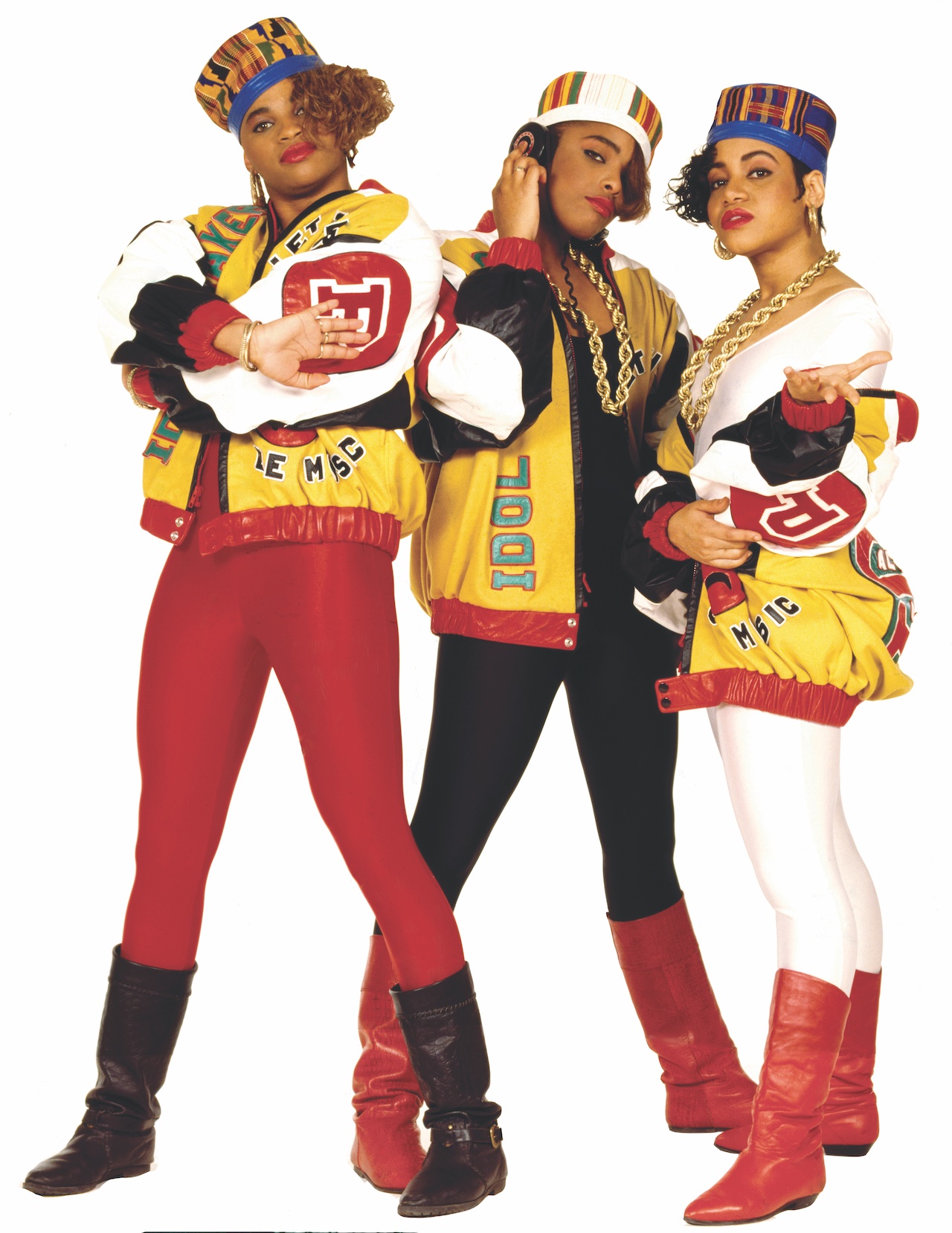

Spearheaded by the Black and Brown youth of the era, hip hop took off, bringing with it a new style that swiftly spread from the Big Apple to the West Coast, and eventually to mainstream media. Once dubbed the “urban” uniform, the look heavily concentrated on customization with an emphasis on popular luxury brands. Everything from DIY creations and custom Dapper Dan jackets to Kangol hats, Timberland boots and even Tommy Hilfiger and Ralph Lauren designs were chosen by the most revered rappers and their loyal fans.

“For us to talk about the relationship that fashion has with those that have helped create hip hop culture, we have to talk about socioeconomic status and access of brands,” Romero says. “Luxury brands were not brands that were accessible to Black and Brown communities.”

While the reliance of DIY creations was born out of the lack of accessibility to coveted, high fashion labels, aspiration played a huge role in the style as well, sparking an interest in logos and brand insignias. Loyalty to brand names quickly became tethered to iconic rap hooks, from Run-D.M.C’s “My Adidas” in 1986, to Cardi B’s 2018 ode to Christian Louboutin with “Bodak Yellow.”

“It was so much about do-it-yourself,” says Way of the early years. “The subculture was young kids who were not the most socially economically elite, so there was this raw creativity and a lot of personalization — iron-on letters, nameplate necklaces, fat lace sneakers, crease jeans.”

In more recent years, it has become commonplace to see hip hop personas sit front row at big-name fashion shows (Gucci and Christian Siriano, to name a few) and create influential partnerships with luxury designers, a far cry from hip hip’s humble beginnings, when “those doors were closed,” Romero says. “The artists were initially dressing themselves. When we think about the idea of luxury in our Black and Brown communities [in the ‘80s and early ‘90s], custom tailors such as Dapper Dan immediately come to mind. He brought trademarks and logos that had this status symbol to the communities to give them access.”

Daniel “Dapper Dan” Day was a bona fide streetwear pioneer, who rose to fame after opening his iconic boutique on 125th street in Harlem in 1982. Dressing hip hop’s shining stars, the couturier gained a reputation for remixing high- end monogrammed materials from MCM, Fendi, Louis Vuitton and Gucci into his own one-of- a-kind sportswear confections. Eventually, his appropriation of the fashion house’s fabrications and logos led to litigation. His beloved storefront was shuttered in 1992, but not before he earned his due credit for bringing high fashion to the fledgling but booming hip hop genre. He went on to sign countless luxury partnerships, most notably with Gucci in 2017. “He was really important in creating a dialogue between American fashion and European luxury brands,” says Way. Footage of the Harlem designer is included in the FIT exhibition, of which Romero says, “What Dapper Dan did in fashion is what young people were doing in music.”

Conversely, brands marketed to a “waspy” all-American audience found themselves in favor of the hip hop aesthetic as well. “Ralph Lauren was a Jewish kid from the Bronx, and he had this American dream that he built through his brand, which really spoke to the aspirational aspect that resonated with people who embraced hip hop,” Way says. “Hip hop kids styled it in a different way, wore it in a different way, and made it their own. But they were looking at what was happening in mainstream fashion.”

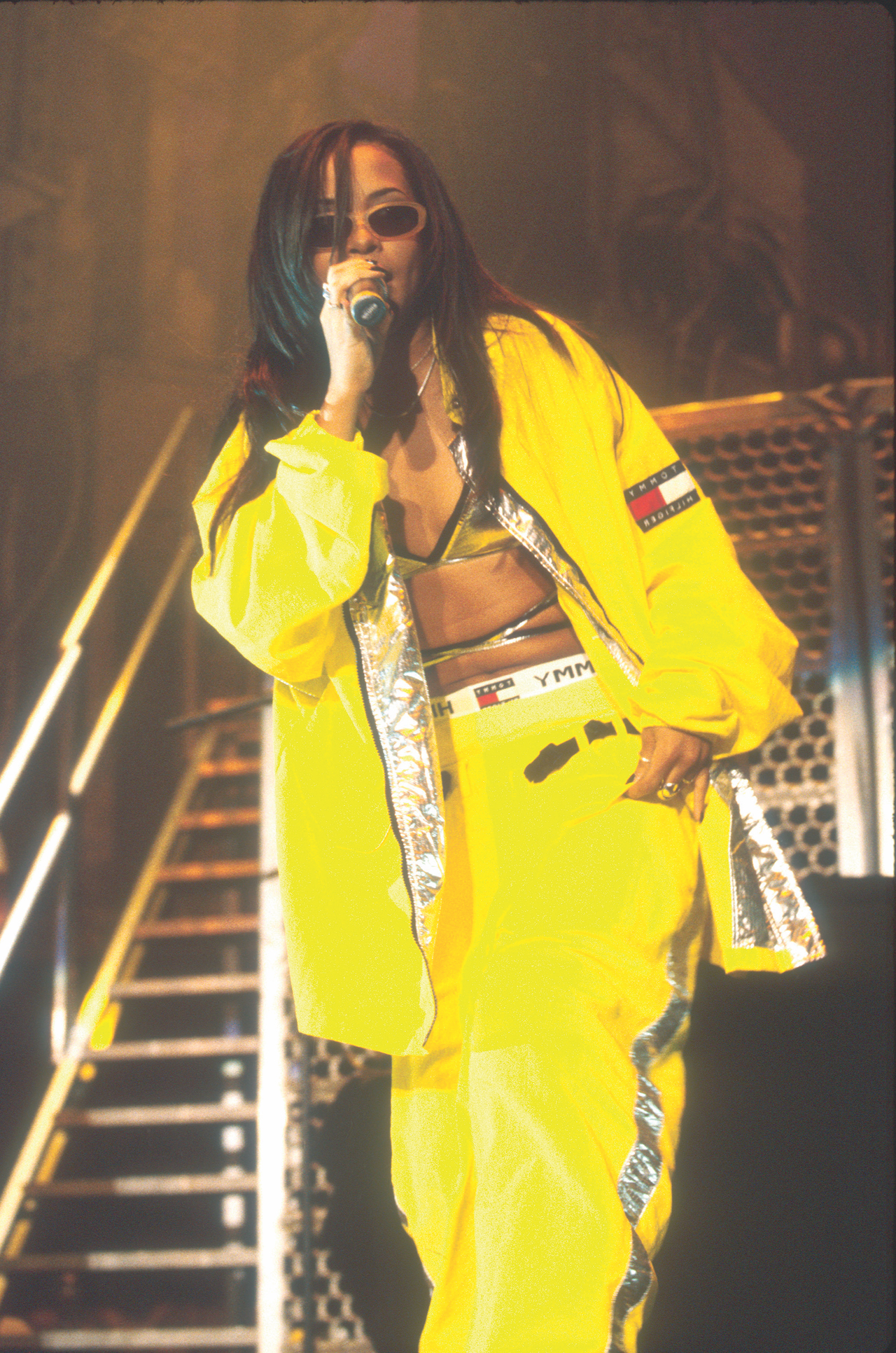

These days, you can’t think of Tommy Hilfiger without picturing Aaliyah in the 1997 Tommy Jeans campaign. The same can be said for Ralph Lauren and the Lo Lifes, who “really brought the popularity of Ralph Lauren to the urban center,” Romero says. The Brooklyn-based crew of young people formed in 1988, emulating the affluent lifestyle while implementing their own hip hop twist. The collective quickly garnered a reputation for boosting apparel, especially from Polo Ralph Lauren.

Read GRAZIA USA’s Winter issue featuring cover star Lizzy Caplan: