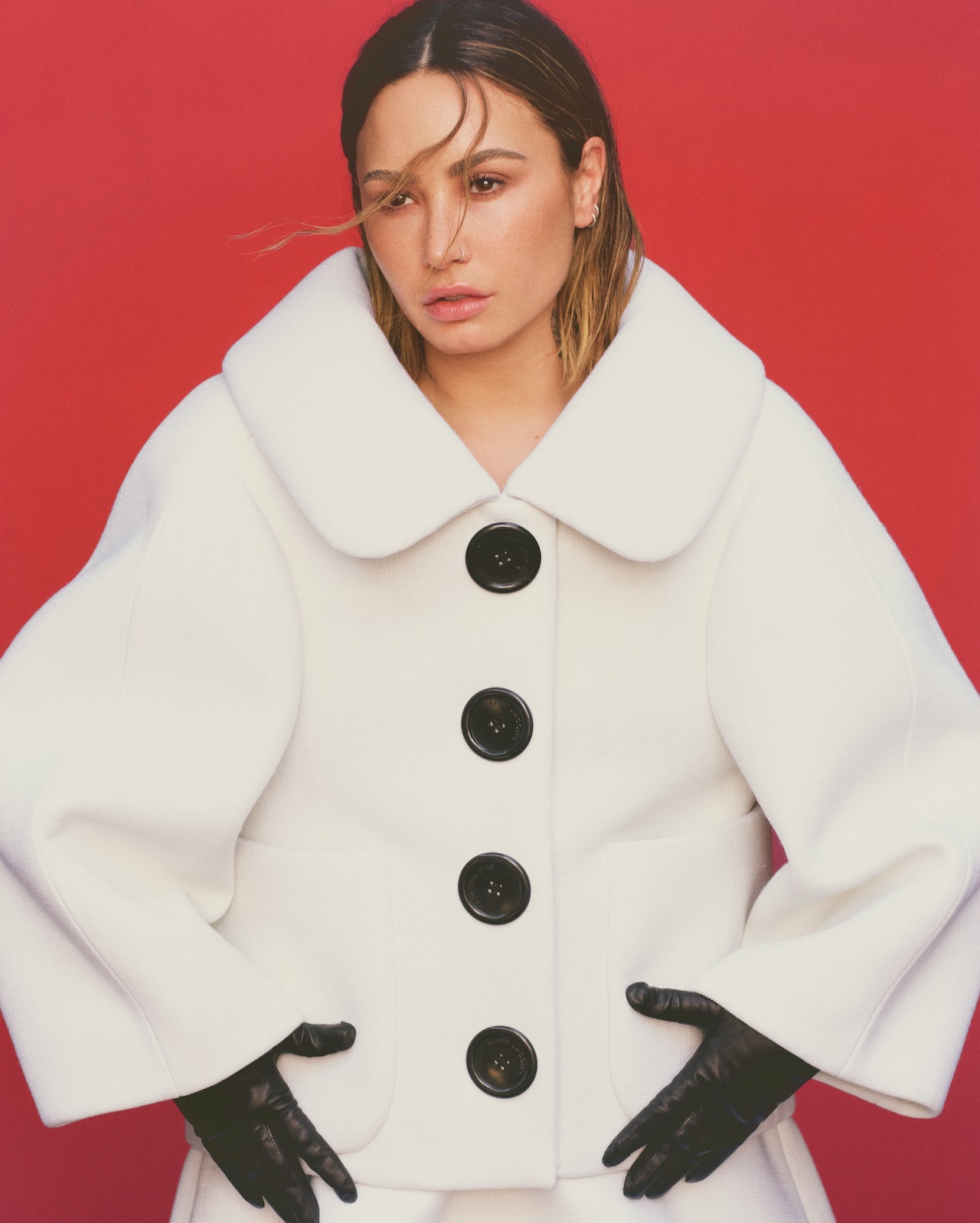

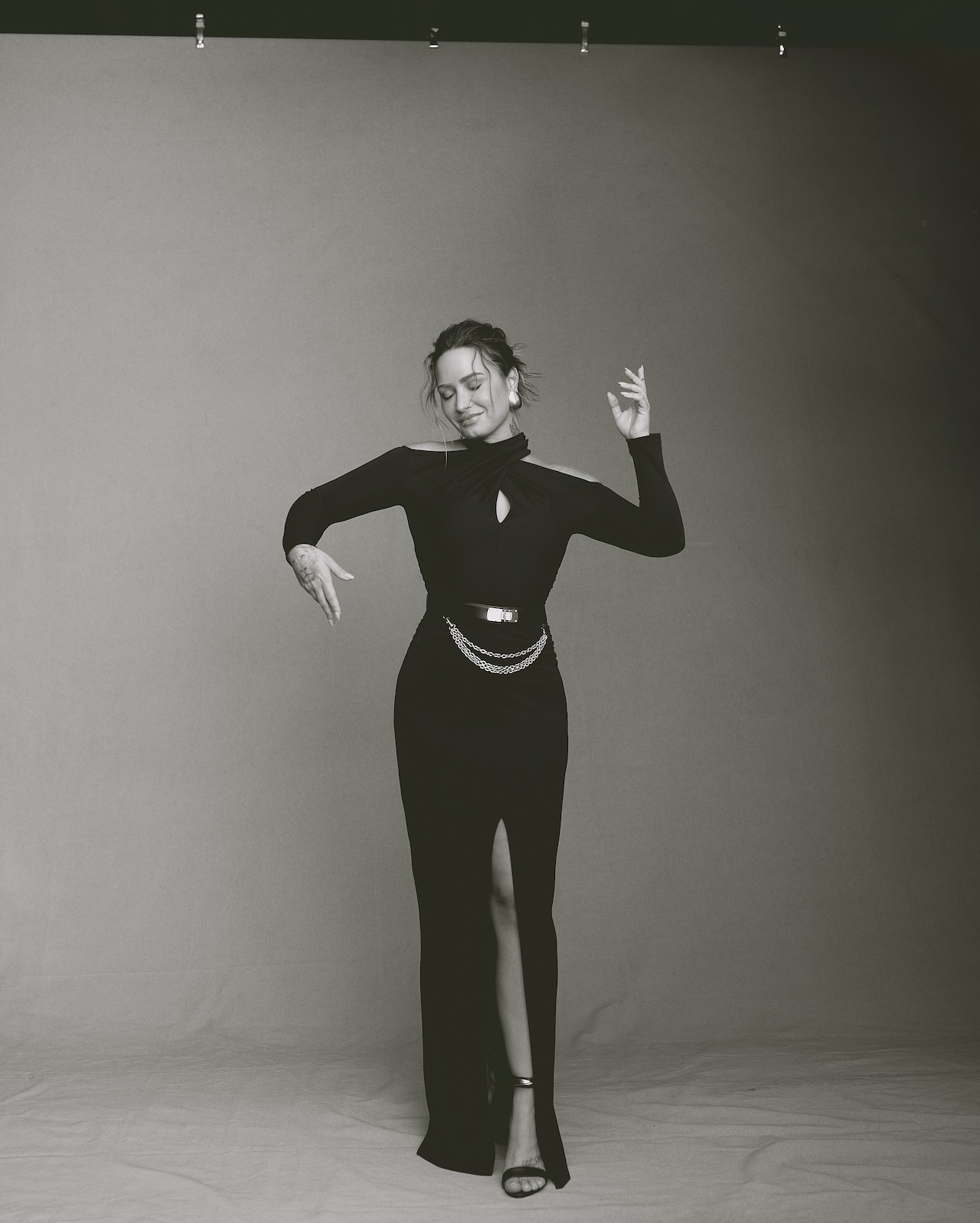

Words by Emilia Petrarca

Before Demetria Devonne Lovato became Demi Lovato—or before she began her acting career on Barney & Friends at the ripe age of eight—she would sit with her great-grandparents in their living room in Irving, Texas, and watch television. “I just have this memory of Shirley Temple appearing on their TV, and I thought: I’m going to be the next Shirley Temple,” she recalls at the beginning of her latest documentary, Child Star, which was released on Hulu September 17. “If she can do it, I can do it. And I did.”

Sounds like a fairy tale, right? A young girl dreams a big dream, chases it, and ultimately achieves it with flying colors. It’s a path so many have sought—and continue to seek. Well, she wants you to know that it didn’t come without a price. “I didn’t realize that it would have such a negative impact on my mental health,” Lovato adds of her nonstop, triple-threat career, which includes dozens of TV and movie credits and eight Billboard-charting albums. “And unfortunately, sometimes that looks explosive, like an incident where you punch your backup dancer on an airplane or you overdose from heroin.”

We’re not even at the film’s five-minute mark, and she’s already laying it all on the table. Both incidents—the first occurred in 2010 and the second in 2018—have been covered extensively. Lovato was the most-Googled person on the planet the year of her near-fatal overdose, and at 32, she’s already starred in three documentaries that touch upon her struggles with addiction, mental health, and an eating disorder: Demi Lovato: Stay Strong (2012), Demi Lovato: Simply Complicated (2017), and Demi Lovato: Dancing with the Devil (2021). So there’s no need to rehash it all here, but Lovato isn’t shying away from her past, either. Child Star arguably marks the beginning of a new chapter for her—one where she can look back at her life and career thus far with some critical distance. As co-director, she was able to go behind the camera and focus on listening and learning.

“At the end of Dancing With the Devil, I turned to my producer, Michael Ratner, and I said, ‘I have a new idea,’” Lovato recalls over Zoom one morning from her home in Los Angeles. She hadn’t seen a documentary about child stardom before—one that takes a more macro approach, tracing the history of children singers and actors, from Shirley Temple to Drew Barrymore to those of the present day, with firsthand interviews that unpack the complex, often harmful side effects of the experience. “I said, ‘I want to do this.’ And he said, ‘Let’s go.’”

Lovato reached out to director Nicola Marsh, whose documentary, Stay on Board: The Leo Baker Story (2022), about a professional skater who is transgender and nonbinary, caught her attention. (Lovato came out as nonbinary in 2021, although she now uses both she/her and they/them pronouns after embracing her femininity once more.)

“I’m grateful that I was able to have those conversations because it made me feel less alone.”

“I’d always seen Demi, but I didn’t know that much about her,” says Marsh, who eventually came on board as co-director alongside Lovato. “And this woman comes down the stairs dressed in black with a Korn T-shirt on and a bunch of piercings, no makeup, glasses. … She doesn’t smile easily. I mean, she does professionally, but she’s quite serious. And I was like, I love this person.”

Together, they made a list of current and former child stars that they’d like to interview. In the end, they got Drew Barrymore, whose career began when she was 11 months old; Christina Ricci, who starred in her first film, Mermaids (1990), with Cher when she was nine; Kenan Thompson of Nickelodeon’s All That and Kenan & Kel; fellow Disney Channel stars Alyson Stoner and Raven-Symoné; and the Gen Z sensation JoJo Siwa. Lovato’s in-depth conversations on camera with each of them are compassionate and shockingly candid, as they relive uncomfortable moments and reveal struggles similar to her own.

“I think we have to hold people accountable so that the future generation of child stars don’t struggle as much as we did.”

“I was tired of being on camera,” Lovato tells me of her decision to direct. She’s staring at her computer camera, wearing minimal makeup; thick-rimmed, black cat-eye glasses; and a black T-shirt. It occurs to me that the disassociation I often feel on Zoom, where I am trying to be present in my mind and body while staring at a small, talking head version of myself, is perhaps some very, very light version of how Lovato has felt her entire life in the spotlight. With Child Star, although she is the one conducting the interviews and her career serves as the organizing principle, she is, for once, not the main subject of the film.

“I think she’d be quite happy for it to be even less about her, to be honest,” says Marsh. “She would say to me all the time, ‘Lord knows the world doesn’t need another documentary about me.’ But I’d tell her: ‘You’re the thing that gives this a voice.’”

Remarkably, Lovato was able to take her ego out of the equation—a rarity for a documentary where one of the subjects’ names is in the credits—and focus on getting the best material she could from others. (She’s so good at interviewing that I tell her she could pivot to a career in journalism, although I wouldn’t recommend it.) “She’s basically being critiqued on camera by friends and colleagues, and she’s owning it and leaning into it,” says Marsh. “She’s also the director, so she could have easily said, ‘Take those pieces out. I don’t think they make me look very good.’ But never once was there even a whisper about toning it down.”

“I mean, you weren’t the nicest person,” says a very understanding Raven-Symoné, who guest-starred in a 2010 episode of Sonny With a Chance, the Disney Channel show on which Lovato played Sonny.

Lovato also has a frank conversation on-camera with Stoner, with whom she filmed Camp Rock (2008) and Camp Rock 2: The Final Jam (2010). “The last few years of working together felt really challenging,” says Stoner, who now uses they/them pronouns. “The treatment did feel drastically different.” They sigh and take a deep breath on camera. “My heart is racing,” they admit. “I do remember a sense of walking on eggshells. There was definitely a lot of fear of a blowup.”

Lovato apologizes and acknowledges that Stoner’s feelings were valid. “It felt good to clear the air,” she says in retrospect. “Talking to people who knew me at a different time in my life was challenging because I wanted to apologize for my behavior. I wasn’t the nicest person to work with at times because I was struggling so much internally, and I was under a lot of pressure. But having those conversations with Alyson and Raven was really cathartic. They were so lovely, so incredible, and so receptive, and I was so grateful for that.”

“It felt good to clear the air.”

Lovato’s interviews with fellow child stars reveal that, unfortunately, her experience was not unique. Many of them struggled with addiction, body image issues, and general feelings of exhaustion and isolation. At least two of them were extorted by the adults in their lives. But thankfully, they can laugh about some of it now. At one point, Lovato and Ricci, for example, compare notes about how they snuck alcohol on set. They also help each other put back the pieces and fill in the blanks, as a number of them can’t recall swaths of their childhoods, perhaps as a trauma response. Before reaching out to Raven-Symoné for an interview, Lovato didn’t even remember that they’d acted alongside each other on her Disney Channel show. “Hearing that from some of the participants in the film was so relieving to me because I thought I was the only one who didn’t remember a lot of my past,” she says. “I’m grateful that I was able to have those conversations because it made me feel less alone.”

In this way, the film is not about any one child star but the machine that creates them—and, in some cases, breaks them. Networks like Disney help to fuel the dream of child stardom with shows like Hannah Montana and Sonny With a Chance, which are about becoming famous, and profit massively off of the merchandise, albums, tours, etc.. But what we don’t often see is how the real-life stars pay the mental and emotional price. Child Star shows the good, the bad, and the ugly, which is notable considering that Hulu is owned by Disney, but it doesn’t point any fingers, either. “My personal decisions led to where I am today, and the accountability is really on myself,” Lovato says.

If she’d known the high price of fame, though, she may not have wanted it so badly growing up, and the film aims to lay out the facts. Stoner cites a statistic that people who experience fame have an average lifespan that is younger than non-famous people. (After her overdose, Lovato experienced three strokes, organ failure, and a heart attack.) They also say fame has addictive properties similar to those of drugs and alcohol. “So if that’s the case, why are we hooking a child to a drug that’s fundamentally altering their brain chemistry and future development?” they ask.

The film is a cautionary tale but also a hopeful one. JoJo Siwa, who is now 21, represents what the next generation of child stardom looks like, which is to say, extremely online. She tells Lovato that she posts anywhere from 250 to 300 times a day on social media—a statistic that shocks even Lovato, who has 266 million followers. “My whole day is filmed,” Siwa says. “There’s nothing left for me at the end of [it].”

Siwa and her generation are more aware of mental health, though, and comfortable sharing their personal identity with the world. In 2021, without meaning to, Siwa came out publicly as gay and held her ground when the president of Nickelodeon called. “Doing that—speaking out and just saying, ‘This is who I am,’ without telling anybody first—I think that was so brave,” says Lovato, who came out as bisexual in 2020. “I didn’t come out until I was 25, so anytime I see someone of a younger age than 25 coming out, I just think it’s so incredibly courageous.”

“That’s why I set out to make this film—to get more answers.”

Lovato doesn’t want to discourage young people from following their dreams, she just wants to protect them as best she can. When she was growing up, the California Child Actor’s Bill, also known as the Coogan Law, safeguarded a portion of her earnings from exploitation and abuse until she turned 18. Social media stars do not yet have these same protections, however, and Lovato has become an advocate alongside Chris McCarty, a Gen Z activist and founder of Quit Clicking Kids, as well as Washington State Rep. Kristine Reeves to put more regulations in place for the next generation. She’s even offered to testify.

“I think we have to hold people accountable so that the future generation of child stars don’t struggle as much as we did,” she says. “I don’t know if that’s even possible—if child stardom just has that effect on people, or if it’s the conglomerates that play a role. I don’t know. That’s why I set out to make this film—to get more answers.”

Considering that so much of her childhood escapes her memory, it makes sense that she’d want to retrace her steps in order to move forward. The film ends on an optimistic note with a song she says she wrote as a letter to her younger self and inner child. “Can’t stop you. / Don’t want to. / Here’s what I wish I knew,” she sings. “The sharks in the water will teach you to swim. / The thorns on the roses will thicken your skin. / People might hurt you and break promises. / But darling, I promise you this: you’ll be okay, kid.”

At the moment, Lovato, who used to do something like 70 shows in 90 days with almost no time off, is enjoying spending quality time at home with her fiancé, singer-songwriter Jordan “Jutes” Lutes, and her dogs, Batman, Ella, and Pickle, as well as her family and friends. She’s in the studio working on a new album, but she’s not rushing it. “I don’t know what it sounds like yet, but we’re moving along,” she says.

On the subject of cooking, a renewed passion of hers, a huge smile crosses her face. “It’s very therapeutic—and a big fuck you to my eating disorder that I used to have,” she says. “I’m working on building my confidence in the kitchen and also finding freedom with food. I’ll find a recipe online or elsewhere, and I’ll make it and give it to my fiancé, and he loves it every time. I think he might be biased, but we have a great time in the kitchen.”

Of course, she’s still a high achiever with high standards. One time, a cake took her four hours to make and “smelled like a fart.” So she started over. The next one took her seven hours. But she’s not giving up and is also being kinder to herself. “I recently made spinach bow tie pasta from scratch, and it was really, really good,” she says, beaming. “I was really proud of that.”

Words by Emilia Petrarca, Photography by Thomas Whiteside, Styling by J. Errico

Hair by Casar Ramirez, Make-Up by Etienne Ortega, Nails by Natalie Minerva, Tailoring by Irina Tshartaryan

Styling Assistance by Chardonnay Taylor & Darryl Anderson, On Set Production by APGNYC