Words by Joan Juliet Buck

The first summer of endless rain, I replaced my waterlogged Repetto ballerinas with jelly boots like a pair of clear hard candies, the mint ones with the cold sheen of melting icebergs that are called Polar or Ice. Opaque at the toe-box, the jelly plastic shed pigment as it rose to become as see-through at each calf as an unwashed window. I liked wearing them over bare feet for a jellyfish-polar bear effect. They were dreadful and wonderful, the perfect footwear for climate change, and I would have them still, had I not recklessly worn them to France, where my Deauville hostess seized up at the sight of them and ordered them out of the house.

The French have been criticizing my feet forever. I was born with six toes, put on pointe at five, love to walk, and shoes always hurt. In Paris in the ‘80s, I came to know the elegant Helène Rochas, who was the incarnation of 20th century performative femininity. She lived by strict rules of self-presentation, never ate fish because it was bloating, separated her eyelashes with a straight pin, wore sober pale couture suits and pumps with two-inch heels. She caught sight of my hilarious summer polka dot platform sandals with giant bows and told me to never wear witty shoes.

“Men have fantasies about feet,” she explained, “fantasies of submission and dominance, and they don’t want any visual jokes to interrupt their reverie and spoil their fun.” She was even more stern as she warned me off what she called les baskets, the French term for sneakers, high-tops, or running shoes. “Jamais, jamais ça,” she said. Never, never that.

I hid my sandals with giant bows and shopped at a boutique Helène had heard about that specialized in wide feet, which is now so long gone you can only find its shoes on Poshmark. I’d grimly shove my stockinged feet into oddly narrow triangular shoes that rose in a slope that seemed gentle but was not, and install the backs of my feet at the exact place where they’d be most efficiently pounded from below at every step by the jolt of metal heel-cap against hard sidewalk. The balls of my feet burned with a high-pitched pain underscored by the dull thud of mashed toes, but I kept wearing those shoes because Helène said the boutique catered to wide feet and the heels didn’t look very high. Each age has its own delusions.

I desperately needed relief from the pain of trying to summon up performative femininity, and occasionally donned the one pair of sloppy gray nylon plastic soled baskets I owned, so I could run errands without weeping. One day, I recklessly ventured into an elegant street where such abject displays of comfort were unknown and where I ran straight into the elegant Helène, who was deeply disappointed to see what I had on my feet. She ordered me to throw out les baskets. I did.

But fashion is a head-snapper, and almost before the garbage men had collected the running shoes—which were, in truth, very ugly—the French magazines were praising Jane Birkin for being “a l’aise dans ses baskets”—at ease in her sneakers. This was a confusing expression, because until Jean-Louis Dumas of Hermés created the Birkin bag for her, Jane Birkin never carried a bag, only huge peasant baskets.

Jane Birkin’s rejection of performative femininity, her proof of authenticity, was lauded exactly when it was most needed: that was the year Hermès began to commercialize the Birkin bag as the symbol of relaxed personal authenticity.

By the time I was running Paris Vogue 10 years later, half the fashion editors came to work at ease in dirty baskets.

But the boss was supposed to teeter about. I wore flats during the Paris Vogue years, Donna Karan mules, lace-up ghillies, anything I could walk in, and was much scolded by fashion legends, photographers, and the two great shoe designers of our time, both my friends, both appalled by the shape of my feet and my insistence on finding shoes that would not hurt.

Shoe designers are just a touch perverse. Manolo Blahnik’s multilingual effusions suggest a light touch, but his taut sketches reveal an implacable will in the swoop of the instep as it plunges from ankle joint to toe cleavage. He’ll set a frizzle of lace or gleaming glass and metal on the vamp to distract from the height of the heel, for which he long ago found the perfectly balanced placement in the precise continuation of the leg, never at the back, never too far forward. For decades, he’s applied this golden rule to his shoes that only hurt if you really want them to. His shoes have so much character that the late Eric Boman shot an entire photo book of shoes paired with their non-shoe twin counterparts, as playful and delightful as a party game.

Christian Louboutin is as playful and takes more risks. He apprenticed at the Folies Bergères, opened his shop when he was 29, made red soles his trademark, and applied what he’d learned about walking in impossible footwear from showgirls to his insanely high heels and even taller platforms. In her 60s, Tina Turner could still dance in them for an entire stadium show.

I collected his golden sculpted heels as distressed as the pillars of ancient temples, red satin ballet pointe shoes with kitten heels, ankle-strap sandals in antique gold leather. I could not dance in any of them for more than five minutes, but at the Paris Air Show, I climbed a skinny metal ladder into some kind of warplane before I realized that I was wearing Christian’s draped silk wedge mules, six inches tall and as hard as a geisha’s getas. The man in uniform climbing the ladder behind me, his nose to the heels of my mules, must have expected me to fall on him at every step. I did not; the built-up mules were steady. A little heavy, very high, they were wide and comfortable.

Those of us whose feet have always hurt suspect designers of being dark princes of fetish-wear, committed to inflicting pain, but neither Manolo Blahnik nor Christian Louboutin design for pain.

Alexander McQueen, though, hewed close to his nightmares and said he wanted people to fear the women he dressed. One day in London in 1998, he terrified a fashion audience by having the beautiful Paralympian Aimée Mullins stride out on prosthetic wooden legs carved with a pattern of flowers. We didn’t know she was a Paralympian, so we interpreted the message as a hint to cut off our legs, so we too could have wooden ones carved with flowers by Alexander McQueen.

Just before his suicide in 2010, McQueen showed disturbing pale green boots he named “Armadillo,” hybrids of reptile and submarine. Now, 14 years after his death, his successor Sean McGirr presented calfskin-covered boots that end in hooves.

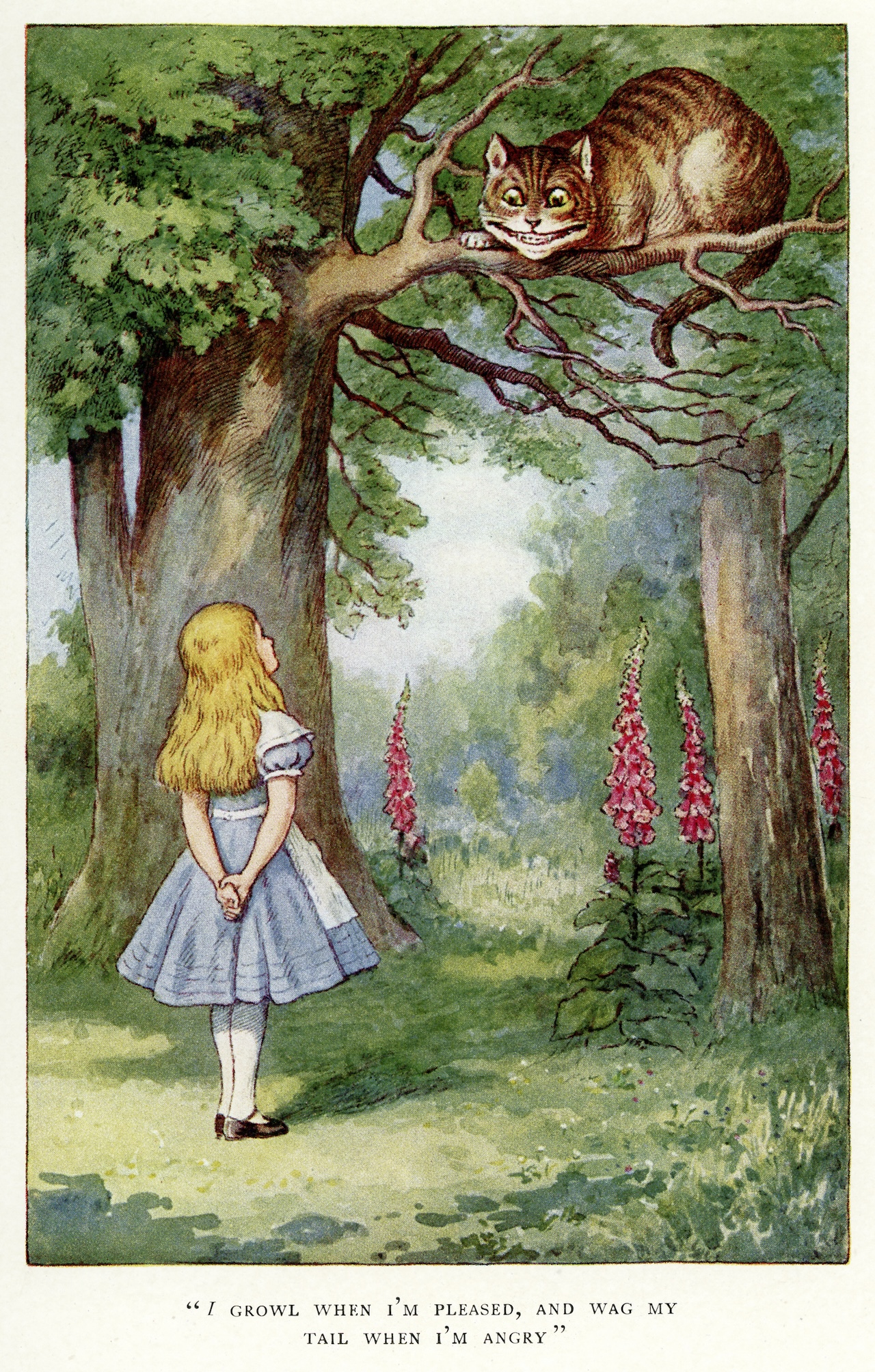

But instead of being horrified, I find this cheery news. The long fight between the pain of heels and the slop of sneakers came to a kind of truce when every woman began to wear some version of baskets, mainly sneakers, with everything, and for every occasion. At the Cannes Film Festival, women refused the red carpet high-heels rule, and flats have become the apparel of resistance. No one cares about elongating their legs any more. Young girls are auctioning off photos of their feet in a sort of OnlyFans situation, and the hottest next shoe is the Mary Jane, so that Alice in Wonderland is deployed against the gender-fluid comfort footwear that belongs in the drugstore orthotics aisle. Classic Nike, hot On or middle-aged New Balance, the shoes—canvas, nylon, polyurethane, Lycra, mesh, or vegan leather—are decorated with laces, elastic straps, Velcro bands, the main components of ankle braces, casts, and foot stabilizers. Their soles—rubber, plastic, or foam—always look squashed. The marshmallow aesthetic leads us straight back into Uggs from 30 years ago, which are basically shearling tubesocks.

But this animal thing gives me hope. I’d had a flirtation with Martin Margiela’s split-toe cloven hoof shoes, but he called them ‘tabis’ after Japanese socks, and they just weren’t animal enough. At the end of last year, to complete the repair of a foot injury, I attended an Alexander Technique workshop. There we were, some 15 of us, in a Franciscan monastery overlooking Malibu, being taught to walk like bears.

Walk like bears? I thought I’d misheard what the teachers said, but no, it was definitely bears. Michael Gelb and Bruce Fertman, who collaborated on the new book Walking Well, explained that bears and humans are both plantigrades, species that walk on the entire surface of their feet. Bears are bipeds only at whim, but we humans have no choice. Stability is earned once we learn how to stop clenching. How to stop tensing. How to stop dreading.

It was so simple, and so long coming.

The other Alexander teachers—there were a pack of them—showed us how to walk like a bear, stable and slow, peeling our bear paws off the ground, one paw after the other. And then there were other animals. The training was fascinating, pleasurable, and it made a difference.

I keep going to these classes, these workshops. At the last one, half the participants were barefoot, the other half shod. It didn’t matter, it was whatever worked for you. On the second morning, a beautiful older woman told us, with tears in her eyes, that she had finally apologized to her feet.