Newsfeed

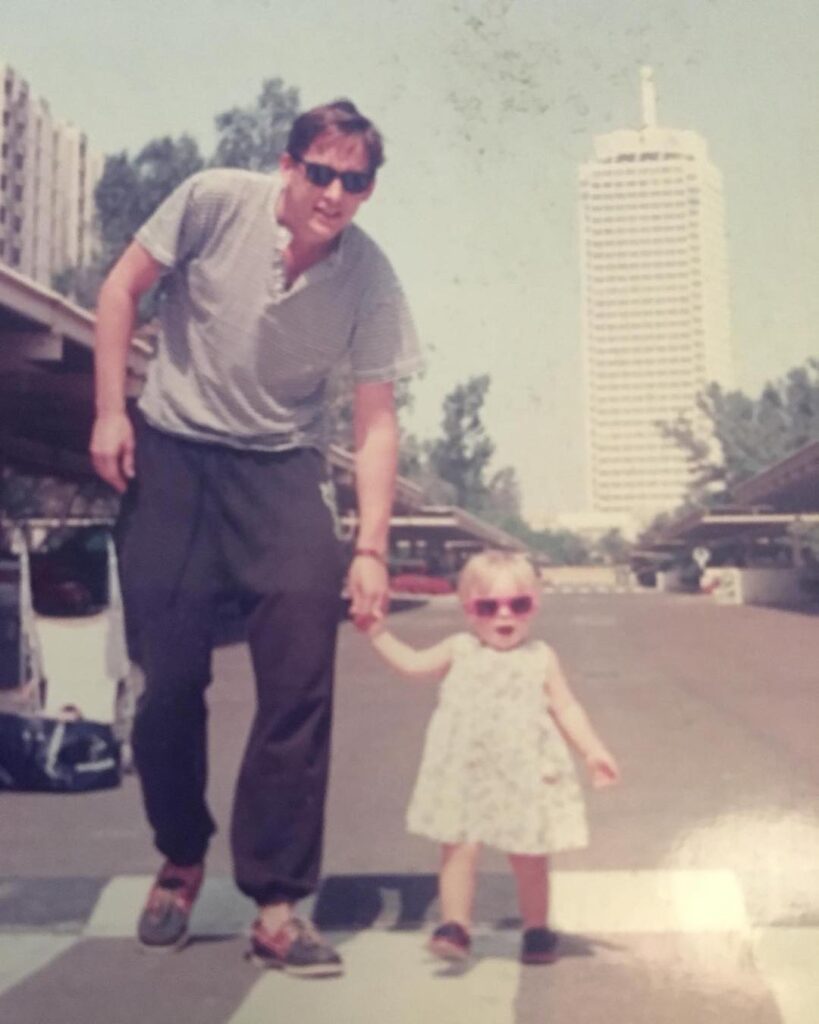

Thirty-two years in one place should make it familiar. But Dubai never stood still long enough to be known in the way other cities are known – through years of institutions, the rhythm of old streets, or buildings that weather rather than vanish and are rebuilt. I was raised in the quiet before the crescendo – before the glass, the gleam, the crash, then the global gaze. Before the desert had an address.

Back then, Dubai felt like an in-between – not a metropolis, not a small town, but something gently forming. We lived simply. My childhood memories aren’t threaded with spectacle, but with softness: camping in the mountains on weekends, walking the dog on what is now known as Kite Beach, swimming in an endless ocean that The Palm now occupies. There were fewer malls, fewer cars, fewer certainties. There was room to be still.

I remember the sea before it was claimed. It wasn’t flanked by swanky residences and designer hotels. Weekends were fuelled by Tupperware boxes and towels. No reservations, no agenda, no DIFC traffic. No DIFC at all, in fact.

And now we live in a different city entirely. The wild has arrived, but it’s not the kind that howls. This is a new wilderness, one of ambition, invention, velocity. Glass towers stretch impossibly tall, roads weave through districts that didn’t exist five years ago. The desert hasn’t disappeared; it’s been built over, carved into, made obedient. What lived as palatial desertscapes in my family photos from the ‘90s now exist as steel rising from sand, air-conditioned and aspirational.

I am excited for what the future brings for the UAE, and I feel a sense of pride to have grown up with the city and witnessing first-hand how this landscape has aggressively and remarkably evolved. But with progress comes a kind of ache. Not regret, not resentment, just a quiet grief and yearning for the small things that didn’t follow us forward. For a childhood that has been built over almost entirely. The iconic Hard Rock Café guitars signalling you were nearing the end of the city; the Marina before it was curated; the Trade Centre taking pride of place as the tallest building on Sheikh Zayed Road…

And yet, I’m still in awe. Because what Dubai has done is nothing short of wild. It has redefined what’s possible – not even in decades, but in years. It has held space for hundreds of nationalities, given rise to artists, entrepreneurs, architects of both buildings and dreams. The socio-economic transformation has been profound: from oil to innovation, from pearl diving to AI labs. This place reinvents itself and continues to move forward and innovate without apology.

We grew up with it. We watched as whole neighbourhoods emerged, as skylines changed shape between school terms, as accents and languages mingled in classrooms and grocery store queues. Ours is a generation raised on third-culture change, where we hold memory in one hand and momentum in the other.

Sometimes, I still hear the old city – at the bottom of a drink in DOSC, the rustle of an Antar wrapper, the sizzle of roadside chai. Sometimes, I see the past in a flash of signage, a scent, a shortcut no longer needed. It’s all still here, you might just have to look a little bit harder.

So I guess the wild is here to stay. In the skyline. In the silence that’s gone. In the boldness of what’s next. But perhaps the wildest part of all is the cohort of third-culture kids who belong to a version of this city that no longer exists. Dubai is not just where I live, it’s my home. It always has been.

And as much as I miss the stillness, I also know that Dubai was always too exciting a place to stay still.

Photography: Aqib Anwar