And then it suddenly dawned on me that fashion’s existence is indisputably essential. Some may say it’s a vital industry because of its influence on pop culture, others may say it’s a necessary tool for self-expression, and some may entirely disagree. “Fashion matters. To the economy, to society and to each of us personally. Faster than anything else, what we wear tells the story of who we are – or who we want to be,” says Professor Frances Corner, Head of London College of Fashion and Pro Vice-Chancellor of University of the Arts London.

“But fashion is too often seen as a frivolous, vain and ephemeral industry. Many people fail to appreciate just how important and wide-reaching it really is. Globally, the industry is valued at $3 trillion. It’s the second biggest worldwide economic activity for intensity of trade – employing over 57 million workers in developing countries, 80 per cent of whom are women.”

Whilst it is undeniable that the fashion industry is an immense one, it’s also true that it can create waves throughout culture and society. Think about how fashion has influenced gender discrimination as well as gender roles, think of how many job opportunities, in particular for women, it has created. Think of how it’s given representation to diverse cultures and minorities. When a hijabi woman like Halima Aden is the face of a major fashion house like Max Mara, that news transcends throughout societies. When a brand like Victoria’s Secret employs a model with down syndrome to be one of the faces of its campaign, it leads to more inclusion and diversity elsewhere. And even when a brand makes a judgement of error, such as when Marc Jacobs dressed non-Black models in dreadlocks, it allowed the media – as well as the people – to engage in the topic of cultural appropriation and to educate themselves.

For designers, fashion can be one of the most effective social tools to engage with consumers on important discussions that need to be had, and to give voices and spotlights to causes that need it the most.

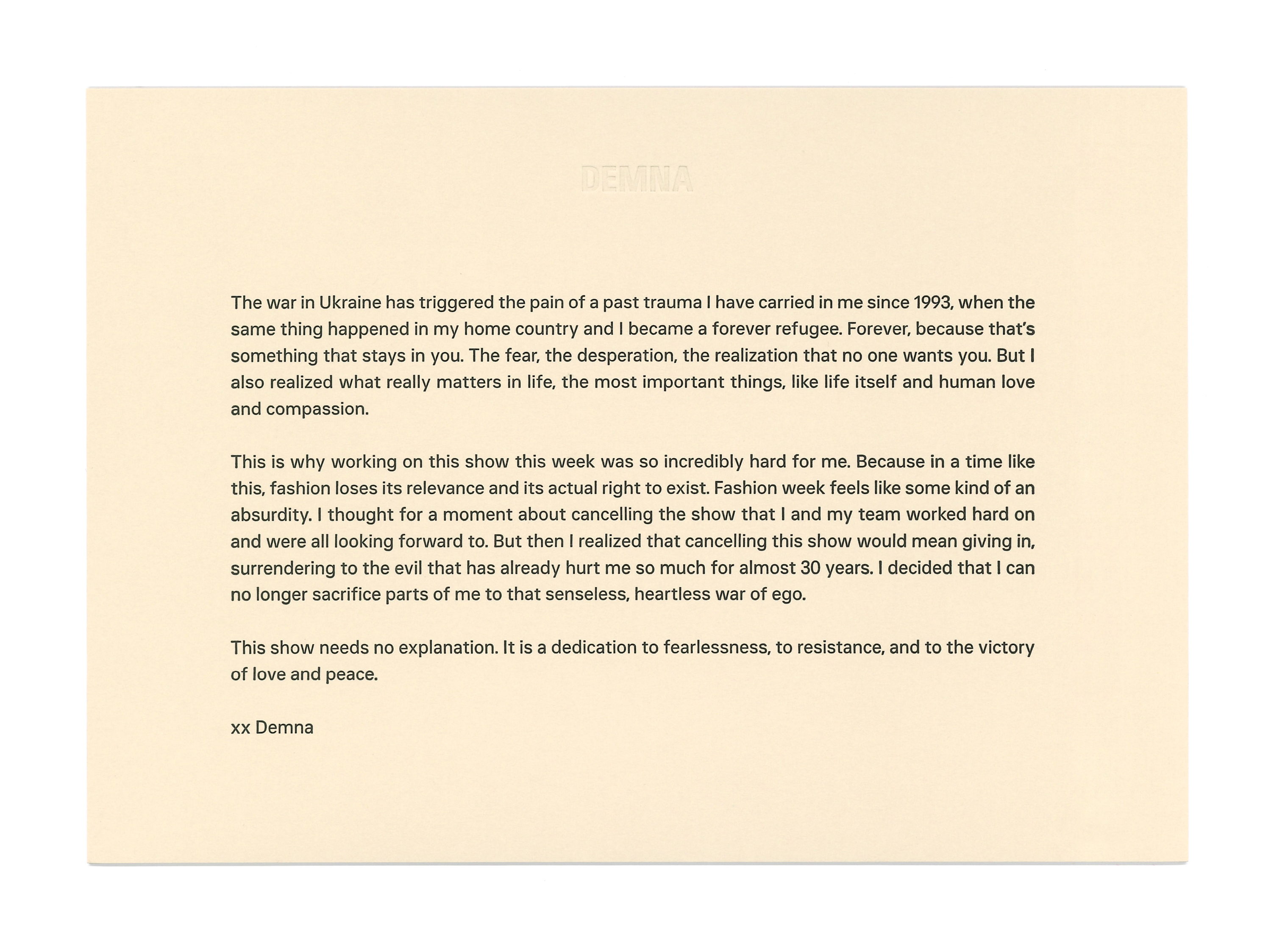

Just as Demna Gvasalia, along with several other designers shed light on the tragedies that Ukraine currently faces, this attention and pressure can be seen as a form of protest to any forms of oppression. Having the final two looks from the Balenciaga show in blue and yellow, representing the Ukrainian flag, was a form of solidarity. Having a celebrity like Bella Hadid walk down the streets of New York in a Palestinian Kuffiyeh, is a symbol of support to those who face oppression.

Whether you may agree or not, it’s undeniable that fashion – just like media – is a crucial instrument in creating social movements, which can be the driving power to real change in the outside world.