Newsfeed

“AND WHEN WE DIE, OUR BONES WILL CONTINUE TO GROW, TO REACH AND INTERTWINE WITH THE ROOTS OF THE OLIVE AND ORANGE TREES, TO BATHE IN THE SWEET YAFFA SEA. ONE DAY, WE WILL BE BORN AGAIN WHEN YOU’RE NOT THERE. BECAUSE THIS LAND KNOWS US. SHE IS OUR MOTHER.” – MOSAB ABU TOHA

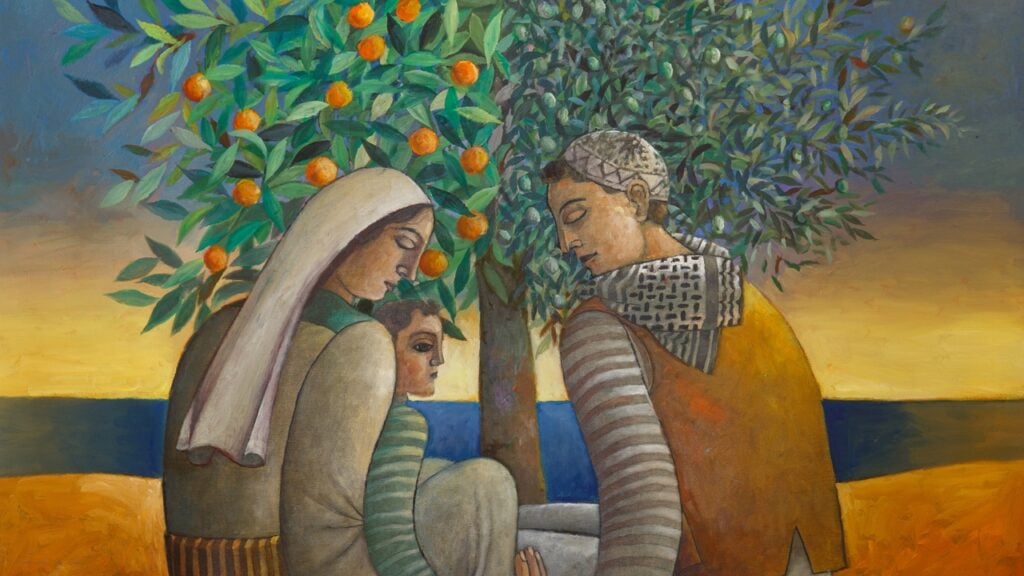

In Sliman Mansour’s From the River to the Sea (oil on canvas, 2021), a woman in a traditionally embroidered dress folds her arms around a trunk of a tree that splices into two lineages: one branch carries the jewelled leaf of the olive; the other swells with the aureate gleams of oranges. With her cheek against the bark, her embrace is faithful as a pact; on behalf of her people, she stays firmly rooted with the crops that have fed families and furnishes an iconography for over a century. For this story, GRAZIA looks to Palestinian artists at home and in exile, textile and painterly, sprawling across generations and geographies. In their hands, the land is a lineage, and art is the ledger that preserves it.

When people think of Palestinian art, their minds go to Mansour, with his terraced hills, his fruits and foliage that crop up across decades of work, his surrealist figures that shift through Palestine’s land and all that it bears. His canvases are thick with allegory. “The olive tree, for us, is not only a tree, but a witness to history and the resilience of our people,” Mansour tells GRAZIA. “Its roots sink deep into the soil, just as our identity is anchored deeply in memory. Every olive branch tells a story of survival, no matter how many times its been cut or uprooted. The orange of Jaffa, with its fragrance and sweetness, carries the longing for stolen homes and the coastal cities we were forced to leave behind, keep those memories alive in our hearts.”

Over the past century, the land has endured the same violent uprooting, forced displacement, and colonisation as its people. Advocacy groups and local communities have long documented patterns of ecocide committed by the occupying power. The campaign to supplant the landscape began as early as the 1920s, when the British Mandate Forestry Service and the Jewish National Fund (JNF) launched large-scale ‘reforestation’ projects, uprooting native ecosystems to implant pine forests that mirrored a European ideal of nature, an aesthetic aligned with Zionist imaginaries. Atrocities committed against the Palestinian people are directly and

inextricably bound up with those in its environment. According to the United Nations, as Israel has sought to eradicate Gaza’s population through bombardment, so too has it scorched the ground beneath them, destroying 95 per cent of the territory’s agricultural capacity in just the past two years.

Archives of the native land are all the more crucial as the Israeli government has deemed Palestinian trees a threat to national security. In August 2025, in the occupied West Bank village of al-Mughayyir, Israeli forces uprooted roughly 10,000 olive trees in three days – some more than a century old. This environmental destruction is a form of collective punishment that severs livelihoods and memory. But this is not new: since 1967, hundreds of thousands of olive trees have been removed and large stretches of farmland bulldozed in a region where the olive harvest sustains many families. Set alongside the planting of non-native species, restrictions on cultivation and foraging, and new settlement plans, the message is clear: unmoor Palestinians from the land that defines them.

For generations, these trees have been cherished companions to the people of Palestine, which was an agrarian society long before occupation. They have borne witness to centuries of familial histories and appear throughout Palestinian art – especially in Mansour’s work – as sentient figures, guardians of collective consciousness. “The cactus, planted along the edges of destroyed villages, stands as a silent witness to the Nakba [the Arabic word for ‘catastrophe’, used to refer to the mass displacement and dispossession of over 700,000 Palestinian Arabs in 1948] and the homes that remain only in memory,” Mansour expounds. “It endures without water, surviving harsh conditions, like the Palestinian who refuses to surrender.” Mansour has always offered his viewers a plainspoken lexicon for reading the living records of his work. “Together, the olive with its steadfastness, the orange with its longing, the wheat with its dignity, the anemone with its sacrifice, and the cactus with its endurance form a full portrait of who we are: a people rooted in the land, sustained by memory, and defined by sacrifice and resilience.”

Among the first Palestinian women to formally study art, Nahil Bishara understood the stakes of preserving a landscape through her creative practice. Her granddaughter, Talia Bishara, who, along with her siblings, has devoted herself to sustaining Nahil’s legacy, recalls that her grandmother’s very name became synonymous with flowers. “She found energy in nature,” explains Talia. Across paintings, ceramics, fabrics, sculpture, and even culinary art, Nahil’s work unfurled in vivid, lustrous depictions of native flora. As Talia notes, Nahil sought to transpose Palestine’s beauty, not only its struggles. “It was important for her that she didn’t just paint the Nakba,” Talia says. “That wasn’t all Palestine was to her… she resorted to the flowers and landscape of the old city to explore all of the materials to capture the beauty of the landscape.”

For some time, scarcity shaped Nahil’s method. “Because the commute [across Palestine] was difficult, access to material was limited. She used to paint on hard cardboard. So whatever she put her hands on, my grandmother would make it something artistic.” For Assad Bishara, another of Nahil’s grandchildren, her canvases also pushed back against a deliberate re-staging of the landscape. “She used to see the circumstances around her, and the landscape was rapidly changing at the time,” Assad explains, citing that from 1905 onwards, over 250 million Aleppo pine trees were planted in the region. “When you see olive trees and natural flora is being replaced by something that is completely foreign… you’re erasing memory, identity, and you’re separating the spiritual body from the physical body.” Her pieces were an affidavit of the land’s Indigenous species. “My grandmother worked as a way of immortalising the landscapes before they’re completely erased.”

Against that erasure, Assad insists on the scale and intimacy of what is native. “Palestine boasts an impressive more than 3,000 species of flowers,” he states. “The West Bank alone has around 17,000 species of its own. The flora is an indivisible part of the Palestinian identity… It’s part of our embroideries with tatreez [traditional embroidery style] in every city… It’s part of our culinary arts as well; thyme, za’atar, akkoub – it’s all from the land. You can’t separate the two.” In this way, artists are archivists and preservationists for the land. “Through culture as a power and art as a soft power, we can change the narrative and recentre it,” affirms Talia.

Palestinian oil artist Maha Zeibak paints from the coordinates of diaspora. She was born in Greece, holds Canadian citizenship, and is now based in Dubai, yet her canvases return unfailingly to Palestine. A recent painting shows a girl seated in the foreground, gazing forlorn at the viewer; behind her, a stretch of tents melt into silvery mountains. “Parts of her body and dress begin to disintegrate, drifting away as if carried by the wind,” Zeibak describes. “She may be emerging from the land, or dissolving back into it. Either way, the two are inseparable, bound together as one.” Working with hyper-real clarity that slips towards the surreal, she places her figures in stark, earthly topographies to illustrate the synergy between the self and the landscape. “In my own work, [agricultural] motifs embody what I think of as ecological belonging – recognising that our well-being is inseparable from the health of the land, its ecosystems, and all living things,” Zeibak says. “For Palestinians, the land is layered with complexity: it has been the site of conflict and loss, yet it also nourishes us with ingredients for the food that carry cultural memory and meaning.”

Estranged from the land, Zeibak frames Palestinian agriculture as a kind of inheritance. “It connects me back to a place I know through family stories, traditions, and the foods that anchor our culture,” she clarifies. Painting these forms lets her hold the feeling of return even when return is not possible. It’s also the way she wants her audiences to receive the work: “To step away from the noise of politics, headlines, and endless commentary. So much of what circulates on social media and in the news can overwhelm and complicate how Palestine is perceived… I want to disarm the viewer, to bypass argument and abstraction. An image can speak directly to the heart in ways words cannot – it can evoke empathy, tenderness, and recognition without explanation. That, for me, is the most powerful form of communication.”

Shereen Quttaineh, a Jordanian-Palestinian mixed-media artist working across textile collage and intuitive stitching, binds the land’s native memory in thread “Agriculture is such a huge part of a Palestinians’ lives,” Quttaineh tells GRAZIA. “Not only farmers, even people that don’t have their own farms have a strong connection to the land. Every one of them has a story about the scent of a lemon tree, or the merrimieh [sage] from their teta’s [grandmother’s] house, or the za’atar they picked that came from Palestine, or the olive oil that they pressed, or their neighbours did, and how it tasted so different…” Born and raised in Kuwait, Quttaineh designs and embroiders tatreez motifs, a traditional cultural practice that has long served as a subtle botanical archive by Palestinian women.

In 1977, Israel’s then-Minister of Agriculture, Ariel Sharon, designated wild za’atar a protected plant, policing foraging and severing Palestinians from customary resources as an attempt to loosen their hold on the land. Quttaineh’s collection, ‘Forbidden Plants of Palestine’ depicts the plants that have been historically restricted from Palestinian foraging, including tumble thistle (akkoub), medicinal thyme (za’atar), and wild sage (merrimieh).

“I try to depict stories I have learned about how Palestinians have been restricted from reaching their own farmlands to cultivate, to forage, and to [practice] the basic human rights of actually picking plants and fruits, eating them, cooking them, and using them for medicinal reasons,” the artist explains. “I delved a little bit more into agriculture and the occupation’s impact on agriculture in Palestine… from [Israel’s] restricting access to water, to the farmland, to creating different walls and checkpoints that make it more difficult for farmers to reach their land, leaving the crops to rot. I felt I needed to do something about it, and what better way do I know than to create art through thread and fabric?”

With the ‘Forbidden Plants’ collection specifically, Quttaineh intended for her tatreez motifs to move knowledge back into hands and across borders. “My main goal was to educate myself and to document these plants,” Quttaineh shares. “I wanted people around the world to know what was happening. I didn’t know; I’m Palestinian, and I live right next door, and I had no idea about the atrocities being committed, in terms of agriculture as well.” As Quttaineh’s work has gained traction, her stitched ‘forbidden’ plants survive in sleeves and circles of hands and in keffiyehs as tactile herbariums.

“Palestinian agriculture symbolises resilience,” Quttaineh declares. “The way farmers nurture life despite their displacement and destruction. People every day [conduct] small acts of resistance by going out and collecting akkoub or plants that they need for their tea and salad, and so on… it’s not just about food or economy. It’s about belonging to the land and carrying the heritage… passing on the collective memory of the youth. It becomes an act of defiance and setting our roots down, that they are deep and cannot be erased.”

Palestinian artist Malak Mattar, who was born and raised in Gaza, began painting as a language through which to process and endure the weight of her world. She was only 13 when in 2014, as Israel rained bombs on her homeland, she took to her canvas for what she describes to GRAZIA as “a way of survival”. Using oil on canvas, mixed media, performance, and printmaking, Mattar’s art manifests in striking colours and ripe symbolism, touching on motifs surrounding identity, resilience, womanhood, and the eternal bond between people and land. “I believe in art’s role in documenting our life and history,” she declares.

The young artist is the author and illustrator of Sitti’s Bird, a tender and luminous tale for children. The book traces how a little girl in Gaza finds solace and hope through the simple act of painting. It’s born of Mattar’s lived experience, offering a rare window into the unyielding spirit of childhood in Palestine. “My childhood memories are of growing up in my grandparents’ yards,” she recalls. “They remind me of home and our right to return.” In her art, agriculture imparts hope and growth. “Olive trees, orange groves, and fields embody belonging, continuity, and the enduring struggle to stay connected to the land despite displacement,” Mattar explains. “In the context of land-theft and the uprooting of olive trees, the land becomes even more precious – a treasure we hold onto with our hearts and art.”

Mattar’s story embodies the healing force of creativity; behind it are the innumerable lives of children living in Gaza, whose own strength in the face of such needless horror remains woefully unseen. In her work, she hopes to lay bare what the land itself means to those being torn from it. “[This art] tells the story of a people who remain rooted, no matter the circumstances,” she says, noting that such work also draws attention to the dangers faced daily by farmers and agricultural workers who risk, and in many cases lose, their lives simply for planting and tending the soil. “The fight for Palestine is not only about people, but also about protecting the land and the life it sustains.”