News feed

“Sexual attraction”, writes Edmund White, “is inarguable (or “incorrigible” as British philosophers say). Who feels comfortable telling someone he may not lust after someone else? To say he may not is only one step away from saying he does not – which is nonsense.”

In the introductory essay for Z, a portfolio of photographic works produced by the artist Robert Mapplethorpe in 1981, White, one of the eminent ‘gay writers’ of the 20th and 21st centuries, asserts that “Whoever feels desire feels it and is the best – the only! – judge of the matter. The religious may prohibit the expression of some forms of desire, but even they do not presume to say that desire does not exist or is evil in itself. The camera records what exists.”

Though White may have been speaking in regard to the politics of desire in relation to race in Mapplethorpe’s (both white, gay men) series of images depicting black bodies, he could just as easily be writing in the context of the malignant debate that continues to engulf Australia’s political discourse in 2017, which has made a costly and enervating blood sport over the issue of whether same-sex attracted couples should be accorded the same human rights as their heterosexual compatriots. Who feels comfortable telling someone he may not lust after someone else? A great deal many prominent Australians, apparently. Nonsense might be putting things mildly.

That the portfolio and its accompanying essay should appear in its entirety (and alongside its predecessors, X and Y [both 1978], as well as hundreds of other works from the Mapplethorpe archive) in Robert Mapplethorpe: the perfect medium, a thrilling new exhibition opening today at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, feels uncannily serendipitous. It is by chance and not, I imagine, through design that the exhibition should open on what is the last advisable day for those interested in casting their ballot before the survey’s deadline next Tuesday to do so. It’s the kind of cosmic symmetry that you imagine Mapplethorpe, a master of composition and form, might derive a perverse kind of satisfaction from were he alive today – to think that the largest showing of his work ever staged in Australia would arrive at the exact moment that the communities he dedicated his life to celebrating might be most in need of beauty’s galvanising properties. Or at the very least, a little self-care.

The work of Robert Mapplethorpe, who at 42-years-old died of AIDS in 1989 just months after a major (and controversial) retrospective of his work, The Perfect Moment, opened in Philadelphia, is enjoying something of a renewed prominence in the collective cultural conversation (though it’s arguably never far from front-of-mind). Last year, at Pitti Immagine Uomo, Raf Simons presented a collection of 58 looks, each one framed by (or framing) one of Mapplethorpe’s photographs at the invitation of the Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation. At January’s Sundance Film Festival, Mapplethorpe: Look at the Pictures, screened to critical acclaim before airing on HBO (the network produced the documentary alongside the directors Fenton Bailey and Randy Barbato). A biopic feature film Mapplethorpe, starring Matt Smith in the title role, is currently shooting; documentary filmmaker Ondi Timoner, who wrote the script based on a story by Bruce Goodrich, is directing the film with the blessing of the photographer’s eponymous foundation.

All of these instances (and more – the photographer’s work has also recently been exhibited in London, Montreal, Rotterdam and Norway) coincided with the 2016 debut of The perfect medium, then a two-part show drawn from the photographer’s personal estate, which the J. Paul Getty Museum and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art jointly acquired in a landmark acquisition in 2011. Co-curated by the Getty Museum’s Paul Martineau and LACMA’s Britt Salvesen, The perfect medium has been adapted for the AGNSW by coordinating curator, Isobel Parker Philip, who has crafted a comprehensive survey of over 200 works from Mapplethorpe’s oeuvre, one that strikes a fine balance between the chronological and thematic development of the artist’s groundbreaking work across portraiture, still life and genre photo. “It’s a great challenge for curators to have,” Salvesen told GRAZIA. “This isn’t a traditional retrospective. We’ve got to go beyond that, and working with the archive means we’re able to do that. Mapplethorpe knew what he wanted his final body of work to be and that’s also really interesting to be able to see.”

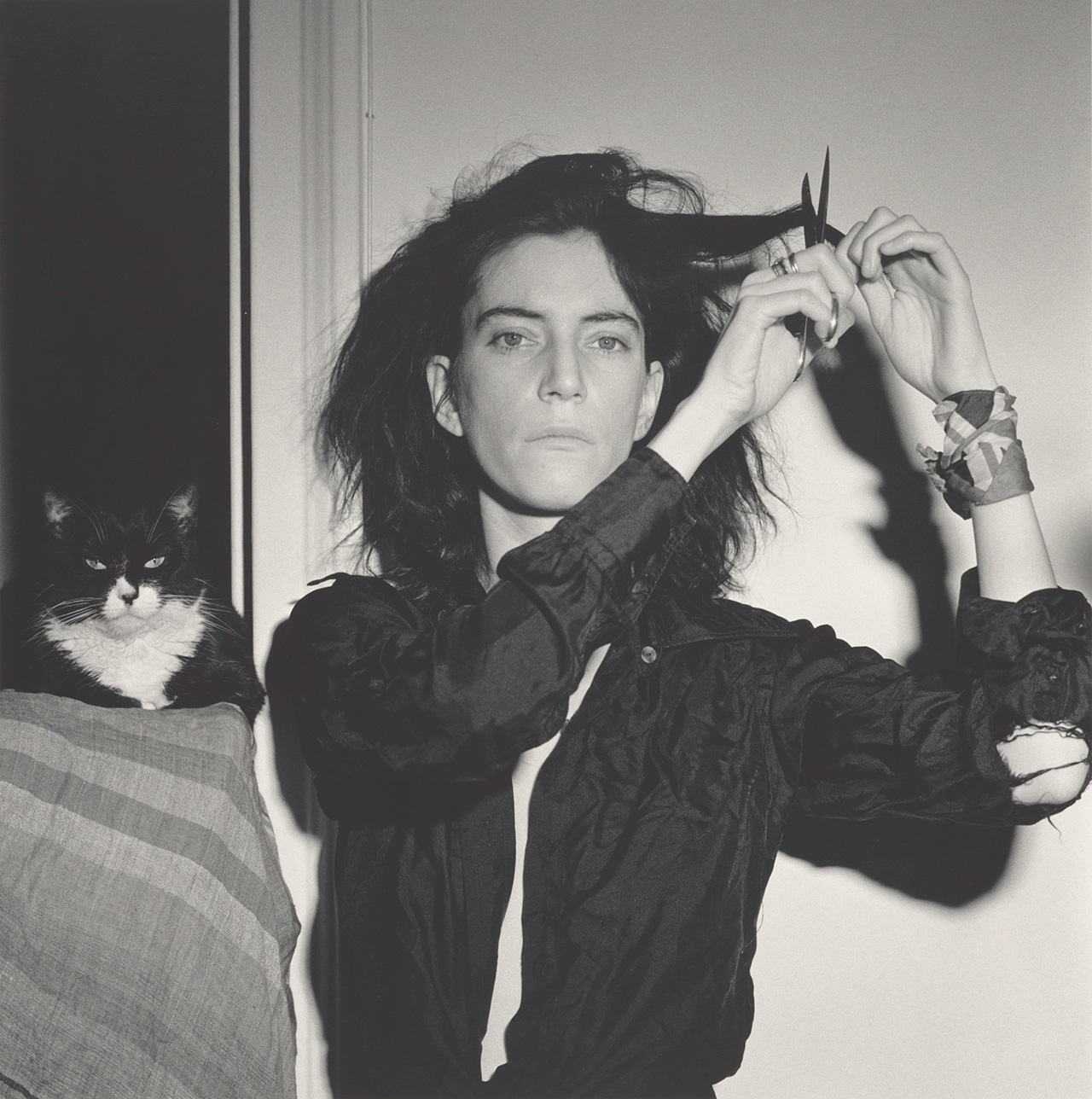

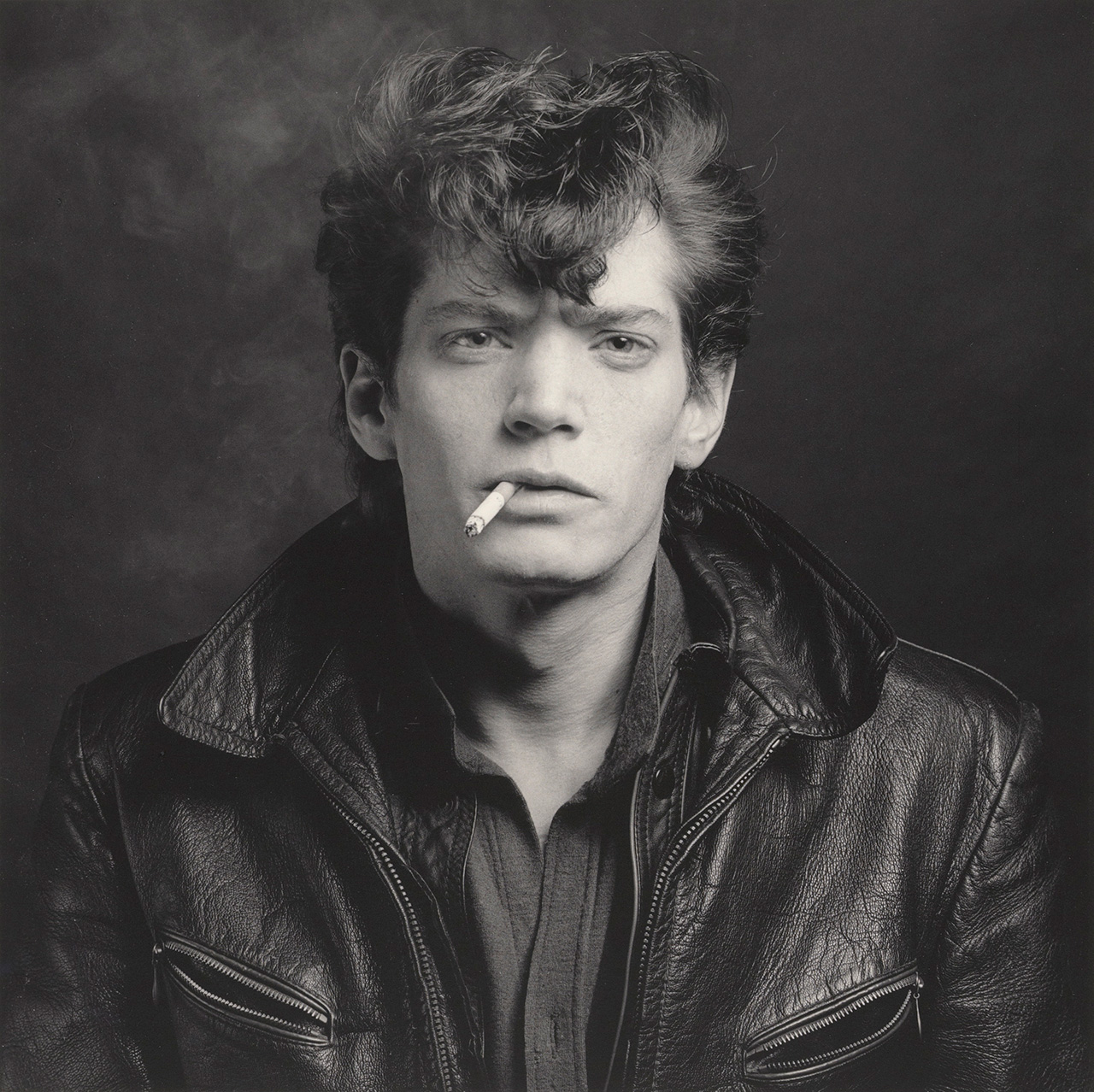

The trajectory of Mapplethorpe’s practice, from early collaged works and assemblages made using found imagery and produced during his time spent studying at Brooklyn’s Pratt Institute and living at the Chelsea Hotel to his late-career refined studio portraiture, is traversed in extraordinary depth. Early polaroids taken in the early 1970s on a camera borrowed from a friend, the artist Sandy Daley, and featuring seminal figures recurrent throughout his career including the artist and musician Patti Smith and his chief patron, the curator Sam Wagstaff, provide a remarkable point of departure for an exploration of Mapplethorpe’s interest and engagement with the photographic medium. Archival material never before seen in Australia – films, contact sheets, magazines and gallery invitations – establish the indivisibility of Mapplethorpe’s private and professional lives, as does the scope of the artist’s subjects, from the stalwarts of the uptown New York art scene, including fellow artists like Louise Bourgeois, to the denizens of its downtown and underground queer communities – his friends and lovers in equal measure.

For many of those friends, Mapplethorpe’s images are similarly indivisible from the mythology of their fame. The magnitude of iconic images of Debbie Harry, David Hockney, Philip Glass, Yoko Ono, Marisa Berenson, Isabella Rossellini, Andy Warhol are as much entrenched in their own artistic prowess as Mapplethorpe’s own with the photographic vernacular. A section of the exhibition dedicated to his singular relationship with Smith will be both familiar subject matter for many, while affording even those with a beloved dog-eared copy of Just Kids new insights into the fruitful and fraught creative and personal partnership between the two artists (Salvesen believes that the 2010 memoir “catalysed a lot of renewed interest” in the artist and his work). Another portion dedicated to his almost decade-long collaboration with the champion female bodybuilder Lisa Lyon achieves a similar affect, and in its contrast with the works featuring Smith it acts as a foil in a way that exposes many of the tensions between two opposing forces within his works: Uptown and Downtown; control and abandon; art historical references and innovation; sacred and profane; male and female; perfection and provocation. The show opens and closes with two suites of self-portraiture – an expression of the idea that you can look at his entire practice as one extended self-portrait, subject and practitioner indivisible from one another.

“It was his disclosure of a much more personal narrative that has really defined the historical equivalence of his practice in a way that, in a post-Stonewall context and in the early days of gay liberation, any public display of homosexuality was an overtly political act,” Parker Philip told GRAZIA. “While he didn’t publicly assert himself as a gay activist his work can be incredibly political in that context [in] the way that he depicted and documented homoerotic desire in all its complexity. He didn’t just reiterate or re-stage the tropes of leather or S&M culture – his photographs derive as much influence from High Renaissance art and from early 19th century photography as they did from the kinds of images that were circulating in the literature of the time.”

The prevailing thematic preoccupations of his career are distilled most keenly into the tripartite portfolios, X, Y and Z, produced in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Each sequence of thirteen photographs depicts, respectively, explicit fetish acts, refined floral still lifes and figure studies of African American men (the latter in particular created a great deal of discussion regarding racial fetishism – hence the White essay). When viewed en masse, Mapplethorpe’s ambition to, as Parker Philip says, “coax a state of equivalence between different forms” is realised most succinctly. It was always, the curator says, the artist’s intention that they be viewed alongside one another, and they’re presented here in a grid-like format that causes the eye to dart across the wall and create those provocative allusions between strikingly realised forms, each no different from the other. Salvesen says that she considers the display, which in the past has been confined to vitrines, a real highlight of this localised iteration of The perfect medium. “The way that he integrated the documentation of sexuality within a formal study and in the pursuit of what he would call ‘perfection in form’ was really pivotal in expanding the expressive potential of the photographic medium,” adds Parker Philip. “His practice, in its entirety, was [devoted to] pursuing beauty and the refined form – using the camera as a device to craft form. Nothing is candid or arbitrary – they’re meticulously crafted for the camera. Even scenes that depict the throes of passion are staged. In doing so, the true legacy of his practice is that he asked that we look at the subjects in a different way. We don’t look at a still life of a flower in a benign way; instead, we see a phallic protruding forms. The same with figure studies: they aren’t candid snapshots. He’s capturing something about these people. With nude figures, he’s trying to make them look like marble sculptures as much as he is depicting the human body.”

The perfect medium is the largest staging of Mapplethorpe’s work in Australia since a 1995 exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art, introducing an entirely new generation to the work of one of the 20th century’s most significant artists. The context in which his work was viewed immediately after his death was highly influenced by the way that it was co-opted by different political factions in the United States. It was used as a device for fear-mongering at the height of the AIDS epidemic in abhorrent ways by both sides of politics, as either a beacon of free speech and expression by the left or a harbinger of moral decay by the right. More than 20 years after those conversations, The perfect medium is an opportunity to look at his work anew divorced from the political weight it was accorded and the retroactive historical significance of those conversations, allowing us to attend to the photographs as art objects – be it a formal study of a flower still life or a male nude – themselves with a renewed gaze. “It’s almost a luxury to be able to look at the photographs themselves,” says Parker Philip, “Because they are so beautiful.”

The title of the photograph Two men dancing tells you everything you need to know about the image, save perhaps for the fact that the bare-chested men are wearing crowns. Salveson says that the image was part of a larger commercial commission that Mapplethorpe executed for a Dutch dance company. Unlike many of his commercial commissions, Mapplethorpe apparently loved the image so much that he decided to incorporate the piece into his official archives. When The perfect medium opened in Rotterdam, one of the subjects attended the opening and Salvesen, who had the pleasure of meeting him, relayed that neither he nor Mapplethorpe believed the image they made together would have the longevity that it enjoys today and would come to embody, across so many years, so many different cultural causes. He’s also just as handsome today as he was then, she adds, laughing. After all, the camera only records what already exists.

Robert Mapplethorpe: the Perfect Medium opens today and will exhibit until March 4, 2018 at the Art Gallery of New South Wales. More information is available here.

Tile and cover image: Self-portrait, 1980, gelatin silver photograph, 50.5 x 40.3 cm, Gift of The Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and to The J Paul Getty Trust. © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation. Used by permission.