Words by Fiorella Valdesolo

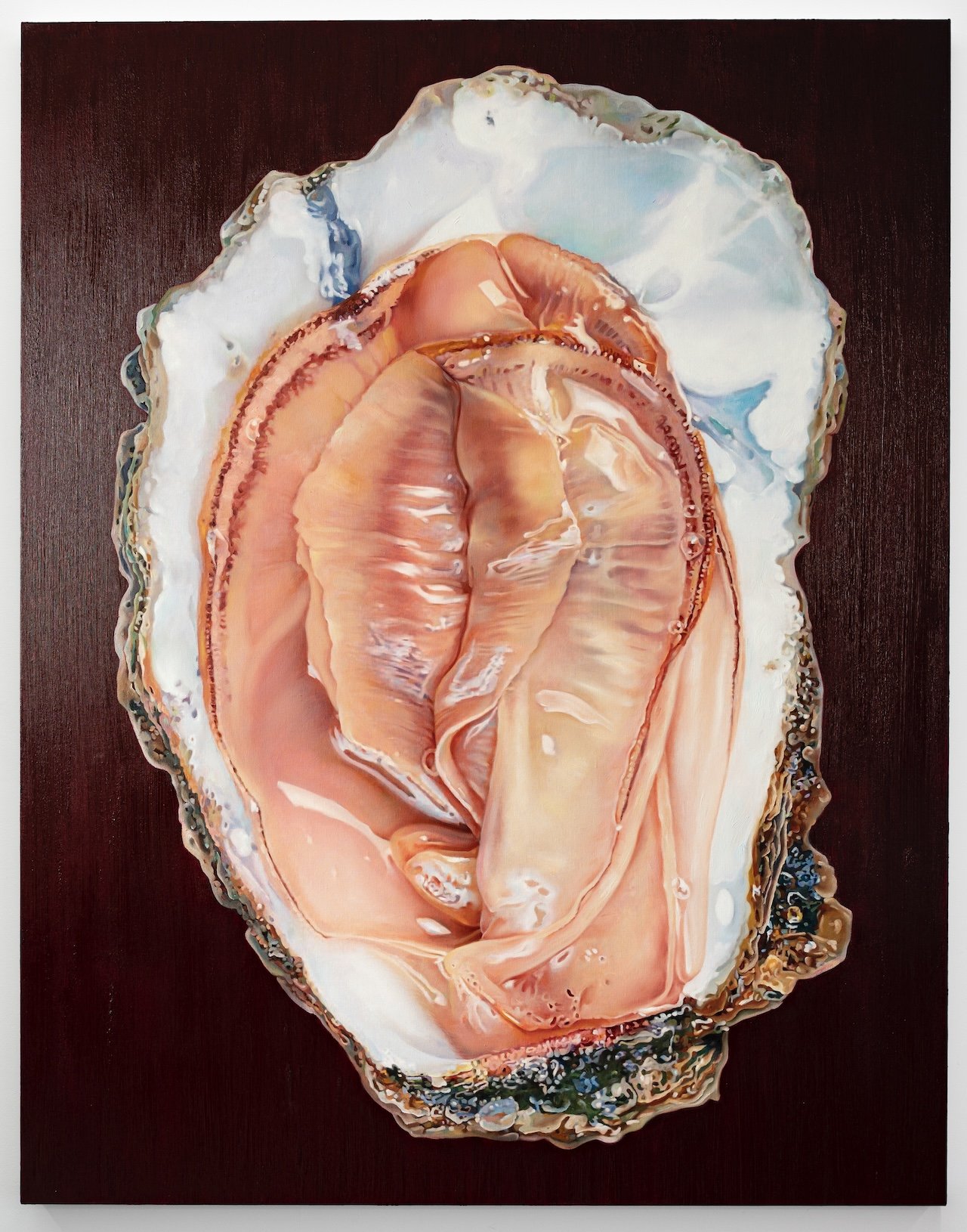

The oyster’s association with desire stretches back centuries. As legend goes, Giacomo Casanova, the 18th-century Venetian whose surname has become synonymous with seduction, would start each morning by slurping 50 raw oysters to, quite literally, gird his loins for a day of sexual encounters. In Greek mythology, Aphrodite, the goddess of love, beauty and pleasure, is said to have been born of the sky god Uranus after his testicles fell into the sea, and she then emerged from the foam of the frothy waters perched on an oyster shell. In the richly rendered paintings depicting domestic settings by 17th-century Dutch Masters like Jan Steen (in 1658’s The Oyster Eater) or Frans van Mieris the Elder (in 1661’s The Oyster Meal) oysters were positioned as devices of flirtation. Something that has continued into this century in films like Tampopo (1985) and Tom Jones (1963), where slurping their moist, briny flesh is a vehicle of temptation.

There are theories about what exactly it is about the oyster that gets our proverbial juices flowing. Scientists point to its high zinc content—they contain more per serving than any type of food; a half dozen oysters has almost five times the daily recommended amount for adults—a mineral that boosts fertility and testosterone levels, which impacts sex drive for men and women. A 2013 study conducted on male mice found that giving them oyster extract increased their mounting behavior (which needs no further explanation). Zinc has also been found to boost dopamine, aka the feel-good hormone, which helps us experience pleasure and has been linked to sexual response. Beyond their chemical composition, there is also their placebo effect: Simply believing that a briny bivalve can boost your libido is effective enough. Because, as Dr. Jennifer Evans, a medical historian and reader in early modern history at the University of Hertfordshire, points out, there are few foods that haven’t been considered aphrodisiacs at some point in time.

“In the 16th and 17th centuries, people were living in a world where they believed the body was very much permeable to its environment, and could also be managed and manipulated, and that included both their fertility and their sexual drive,” says Evans. Food was medicine, and there were many foods believed to heighten one’s sexual desire, some more appealing than others. Evans points to one 17th-century theory that for men to sustain an erection, they needed to consume vast quantities of beans and peas to have windiness in their body. A gut swollen with gas would, in turn, also inflate the penis, an idea that, says Evans, was thankfully short-lived. Evans also highlights the writings of Swiss naturalist and philosopher Charles Bonnet who wrote that salinity qualifies something as an aphrodisiac, sea salt stimulating because Aphrodite was born of the sea. Then there is the notion of an aphrodisiac by association: If something is rare or expensive, and therefore more unattainable, that can add to its appeal. In the 17th century, says Evans, oysters were bountiful and relatively cheap (not so nowadays, of course) but something like chocolate was harder to come by and, therefore, desirable.

Both back then and now, the context of where you are enjoying an oyster impacts its potential to titillate too: shucking and slurping at a roadside oyster stall hits quite differently than doing the same in a dimly lit dining room. In Consider the Oyster, legendary food writer M.F.K. Fisher’s 1941 book devoted to contemplating their appeal, she writes: “Often the place and the time help make a certain food what it becomes, even more than the food itself.” But context also plays a role in how an oyster actually tastes. In the world of wine, we have terroir, a word that speaks to how the soil and climate and topography of one region versus another is expressed in what you’re drinking; in the oyster world, there’s merroir, which means “of the sea” and abides by the same principle, but with water as the ever-evolving landscape. “Oysters soak up the flavor of their home waters—the tides, the seaweed, the silt, the minerals, even the moon’s pull,” says Sims McCormick, co-founder of Real Oyster Cult, a farm-to-your-table oyster delivery service. “But salinity? That’s the loudest voice in the room. It tells you an oyster’s origin story.” Crisp and salty, that’s likely East Coast, says McCormick. Mellow brine with cucumber and melon, you’re in West Coast territory, and balanced with a minerally bite, it’s pure Canada, she adds. Deriving a particular pleasure from an oyster that is literally close to home is common. For the oyster aficionado, it’s their Sailor’s Valentine from Duxbury Bay in Massachusetts. “Eating a Sailor’s Valentine is like sipping the bay I grew up swimming in and sailing on,” says McCormick. “A deliciously fresh and salty sense memory that connects you to the essence of the sea.”

French filmmaker Agnes Varda was famously fixated on the ocean, beaches showing up again and again in her work. In Varda by Agnes, a 2019 documentary about her, the camera follows along as she strolls across the sand. “If we opened people, we’d find landscapes,” she quips. “If we opened me, we’d find beaches.” It’s hard not to see the oyster’s particular allure as one that is deeply rooted in the earth from which they spring forth. And at a time when so many people feel increasingly disconnected from nature, the oyster’s not-so-subtle invitation to taste the ocean offers a powerful and primal kind of pleasure that’s unmatched.