Words by Joan Juliet Buck

You can’t be friends with a fashion designer without wanting their clothes. If you don’t wildly desire what they make, you have no reason to be friends with them, right? Designers know and use the fact that women will fall in love with what they make; models are sometimes paid in clothes and happy about it. The pay becomes a gift and seals the model into the creative process.

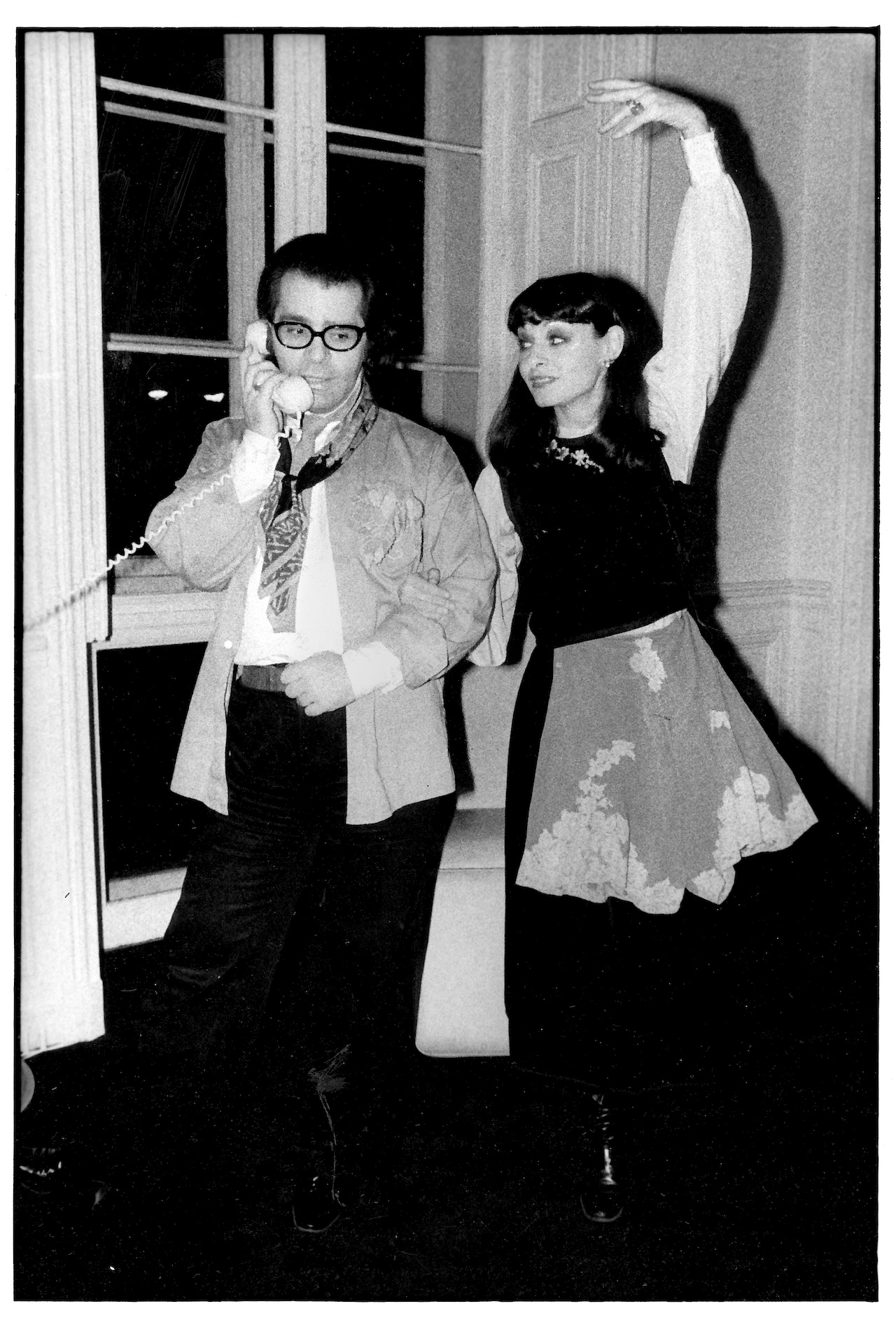

When in 1983 Karl Lagerfeld went from being the multifaceted designer for Chloe and Fendi to animating the legacy of Chanel, we had been friends ever since the illustrator Antonio Lopez had introduced us at the Café de Flore. On most of my visits from London, I stayed with Karl at his place on the Rue de l’Université, which back then was the side wing of the mansion into which he would eventually move. We had been such good friends that Karl’s offer to make my wedding dress was good enough reason for me to get married. When he was designing the dress — between collections of Chloé, Fendi, other gigs — he would fly me over to Paris to choose the antique fabrics, to try on tricorn hats or purple-bronze leather boots. The dress, I must explain, was a four-part riding habit in the manner of the 18th century, composed of an antique mauve silk taffeta underskirt and a bodice, both edged in pleated ruffles, and an equally antique silk ottoman in a slightly deeper shade of mauve cut into an overskirt and a tight jacket, the wrists and bodice of which were embroidered by Monsieur Lesage with antique bugle beads in silver and pearl. The tricorn — antique mauve silk ottoman, of course — was the only possible headgear, with a puff of mauve tulle erupting behind like a smoky tail.

No one questioned my choice of a color associated with half-mourning for my wedding dress; they all must have known this marriage would barely last five years.

Karl was profligate with gifts and sometimes played favorites. Which dress to what girl? The Schiaparelli jacket that remains my treasure to this day came from a vintage dealer’s loft near the Bastille and almost went to Pat Cleveland, but thank God we all agreed it looked garish on her and restrained on me. “It may not be Schiaparelli,” said Karl. “It may be Louiseboulanger, and that’s spelled in one word.”

I have never found out, and it’s simpler to say “Schiaparelli” than to say “Louiseboulanger, and that’s in one word,” so that’s what I do.

By the time Karl stepped in the house of Chanel, we had been staying up half the night talking about books, old movie stars, and the history of fashion for a good 12 years. He knew I loved the novels of George Sand and gave me all 18 volumes of her letters in an edition by Garnier that unfortunately had bright yellow dust jackets.

Because of Karl, who carried a small black clutch with the silver initials M.D, a gift from Marlene Dietrich, I knew that her stage costume was made of an embroidered silk chiffon called Soufflé. To teach me movies, he took me to see Louise Brooks in Lulu and Diary of a Lost Girl. To prove to him that I knew how close he was to the spirit of Paul Poiret, I laboriously copied out George Lepape illustrations for him at the Musée des Arts Decoratifs. His designs for Chloé were delicate crêpe de chine tea gowns and shrugs in a style that owed a lot to the period between Art Nouveau and Art Deco, and he sometimes gave me a dress, though more often he presented me with strange flea market finds, like the mauve chiffon old lady panties with lace inserts. He knew how much I loved mauve, but those inserts also matched the lace on the blouse I’d worn the first time we danced the tango together. Double connection.

I desired the clothes he designed and the antique clothes they were a little bit based on, and everything I loved floated in a private, uncommercial, slightly renegade flea market space of our own. Nothing was expensive. I could desire the dreams without any ka-ching.

But then the stakes ramped up. After years of fashion desire fulfilled by a satin handbag or some old crepe de chine, I spied a mauve fox Fendi coat in a store in Beverly Hills. The shock was intense. It was mauve, it was designed by Karl, how was it possible it was not mine? It had to be mine. It took several years before the fox coat materialized in my life. And by the time it had, Karl had gone to Chanel. He’d taken off into the stratosphere of fashion, where clothes were status and money and commerce, solid universally recognized brands.

Because of his new role, he was no longer a private treasure, but a very busy public figure. I suddenly knew what it was to desire things that everyone else wanted. I was no longer his houseguest; I was almost an onlooker.

It hurt. Karl now had a hedge of people around him, so it was no longer simply a case of hanging out and pointing at what I wanted, or moogling around flea markets and vintage dealers to pounce on gold braid. The fulfillment of my fashion wishes was no longer a sure thing. As in any love relationship when you are not sure of getting what you want, you become insecure and shrink to a fraction of your height.

I went to the Chanel boutique on the Rue Cambon, unannounced, almost like a spy, to see how his eye had remade that world. The surfaces were hard white lacquer and glass, and so terribly clean. The boutique was so organized, so commercial, so sleek and uncompromising. The thick wool tweed suits that had been the mark of lady mayors and minor government ministers, now redesigned by Karl, were suddenly such haikus of style that my fingertips barely dared touch them.

They were so beautiful. And so well set off by the polished cleanliness around them.

If I dared, I could be this new woman he’d invented. Delicate, ladylike, dignified, important, discreet, blossoming within the laws of his new country.

I wanted a black tweed suit so much I could barely breathe. But I wanted it as a gift, the way you want an apology or a kiss; it loses its value if you ask for it. I had to position myself where my desire for the suit — and a few other things, it was time for my first Chanel bag, a black ciré raincoat, and why not that cashmere cardigan with the gold buttons? — would be visible to Karl. I had to be where the legitimacy of my longing would ensure the prompt granting of my wishes.

There was much maneuvering; many people, many lunches, hints dropped, chance encounters arranged. I wanted that suit and that raincoat so much — oh, and the silk crepe blouse with the floppy crepe bow at the top of the V décolleté, and the bag, and, oh, of course a pair of the black tipped shoes, and the tiny triple-ply black cashmere cardigan with the gold buttons on black satin edging.

I felt empowered by the ambition of my wanting, by wanting things with price tags I had not looked at, and I felt diminished by the idea that maybe I would not have them, maybe I did not deserve them. It was like being Alice in Wonderland with the “Drink Me” bottle that kept changing her size, like Alice tantalized by the disappearing Cheshire Cat. Would the suit the shirt, the raincoat, the shoes, and the bag be mine?

At last, they arrived, and miraculously, within the season for which they had been designed, unlike the fox fur coat, which had dawdled in limbo for years.

Another season passed; I was afraid to try the same maneuvers again, so I let it be. Maybe Karl had forgotten our shared communion with the past.

But then came the unimaginable gift. Karl dedicated his Fall/Winter 1984 Chanel collection to George Sand. Ines de La Fressange walked the runway wearing white satin blouses cut exactly like the bodices George Sand wore in the daguerreotypes on the covers of her correspondence in the bright yellow Garnier edition. My George Sand! Our George Sand! Karl had made a baby from George Sand and Chanel!

Here he was, publicly honoring the private letters of my idol, acknowledging her private desires as expressed in the 18 volumes he had given me.

George Sand was twice his gift, and I hadn’t had to ask for it. His salute to what we both loved emboldened me. I could tell Karl everything I wanted in that collection, because it so clearly was mine. And because it so clearly was mine, I didn’t have to ask for much. Sometimes what you want is already yours.