I wore the new diamond necklace today and ran errands around the village with 62 identical brilliant-cut stones snaking down the front of a sturdy old cashmere crewneck. The plain ribbon style of the necklace is known either as tennis or rivière. I prefer a river, any river, to a sport I’ve never mastered, so I’ll go with rivière. The opera-length 18 inches of the rivière make it too long to be visible under the sweater, so it has to be worn balls-out. And it was.

My other diamond necklace, bought on Lexington Avenue in 2021, has a more elaborate design of 30 stones pear-cut into rigid frozen teardrops, 15 headed east and the other 15 headed west to meet in a central but inconclusive confrontation, not pointy-tip-to-pointy-tip, but ass-to-ass. The Lexington Avenue necklace is shorter, which allows it to twinkle enticingly at a neckline, a suggestion rather than a declaration.

Today, I wore the declaration. Strangers smiled at the improbable river of diamonds, and I smiled back. The necklace and I brightened the atmosphere everywhere we went, which in turn brightened me, and I basked in this shared delight until I made my very first visit to the craft shop. The owner, polite but strangely cautious, appeared to think I was out of my mind, wearing old clothes and a diamond necklace in the middle of the day.

I’m not the only woman in Saugerties to do this.

The other one complements her diamond necklace with glass skin makeup and furry lashes to work the checkout counter at the supermarket.

The first time I saw her, my reaction was incomprehension. I’m used to bearded boys with eyeliner and torn fishnets, nose rings have become standard, blue hair a cliché, tattoos banal. But the sight of a middle-aged woman wearing well-chosen bling and cutting-edge professional makeup to work a checkout counter was so gloriously bold and joyful that I was alarmed. At first, I suspected she might be unhinged, but the beams from the stones on her necklace and bracelet looked so positive and had such humor that I realized that it’s a public service to jolt the status quo by spreading enchantment.

So there I was at the Saugerties Antiques Center, the last remaining cave of marvels where I go to stare at oddities and treasures and discuss matters of proportion with the owner Dan Seldin. I like to tell him things like “at a certain age, it’s best to give up showy bracelets so as not to draw attention to your hands, and to wear something bright near the face.”

I reached for the necklace of 62 fake diamonds, the diamond rivière, and tried it on. The stones are not graduated, a style that always looks as careful-creepy as a circle pin from the ‘50s. They’re all the same size, a long straight line as disciplined as the necklace I’d run through my hands at Tiffany’s years ago, before an event for Paloma Picasso, who was launching her own line. Paloma, her first husband Rafael, his best friend Javier, my first husband John, Tina Chow, André Leon Talley, and I were all young and delighted to be given the run of Tiffany’s. The staff indulged our excitement, and I was told “of course you can try on that rivière,” as someone handed me the bright flexible 18 inches of real round diamonds; not the Elsa Peretti diamonds-by-the-yard lite version, but a serious little freight train of closely ranged carats. I had weighed the necklace in my hands and tried it on, but very fast, as if trespassing in a garden at night, and then handed it back before I’d even looked at myself. Too much money, too much responsibility.

“Diana Vreeland’s word was divine, Beatrix Miller said ravishing, Julie Britt wanted inspiration, and in France, nothing would do but sublime.”

Years later, a good friend was given an almost identical necklace by her husband. A long, plain, austere line of emerald-cut diamonds, it was so well-pedigreed and so expensive that it inflamed the shyness she’d fought all her life. She wore it so discreetly hidden that you could barely see it, and when my eye caught a little glimmer from the rectangular stones, they looked too narrow, a little punishing, not at all fun.

I believe it cost a fortune.

The one I tried on at the Saugerties Antiques Center was the price of a dinner for two.

“It looks real,” said Dan Seldin.

“I don’t want to look rich, I don’t want to excite envy, I just want the brightness and the light,” I said. “I don’t want it to look real.”

Fashion feeds on fantasy, and fantasy, by definition, is not real. The great fashion magazine editors used the vocabulary of rapture and transcendence to signal approval. Diana Vreeland’s word was divine, Beatrix Miller said ravishing, Julie Britt wanted inspiration, and in France, nothing would do but sublime, a word spelled the same way in French and English. (This was before fierce and sick and dead and bussin’ and BDE and GOAT. Before the French honored the age of grunge by replacing sublime with destroy.)

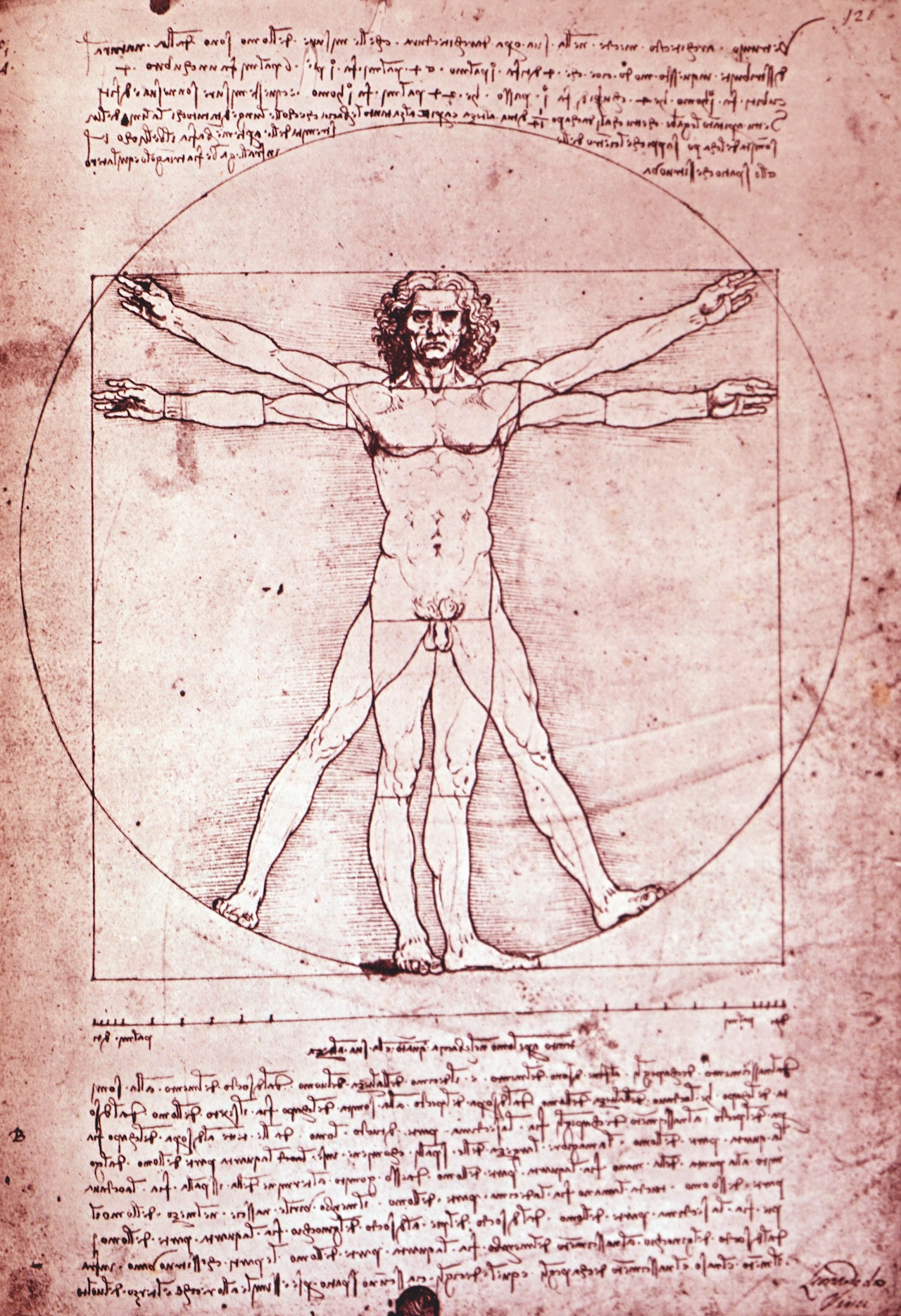

The truth is so simple: Our eyes need to be fed with beauty, our brains respond to harmony. Humans need shapes, colors, and sounds to come at them in certain proportions. Harmony makes sounds into music, and it doesn’t only come from art, but from everything. Harmony is aesthetics and grace; some argue that it is God.

Everyone needs beauty.

Even those who fear museums love sunsets.

The laws of harmony set out by Euclid around 300 B.C.E apply to geometry, mathematics, music, art, nature—what can be heard and what can be seen. For the scientific, it’s the golden ratio of 1.618. Never mind that ratio—I can never get my head around mathematical concepts, but all you have to do is look at the diagrams that express this golden ratio to recognize things you have seen, including the layouts of magazines.

And what the golden ratio tells us is that musical notes, colors, and shapes that connect in its unique, specific way—1.618—have the power to make people happy.

The golden ratio means you can calibrate the world around you to produce harmony and become an instrument of joy.

That joy is separate from price and pedigree, because it belongs to the vast and magnificent world of play.

There’s a reason it’s called costume jewelry: It’s made to dress up in. It does not try to convince you it’s real but invites you to come in and have fun.

“That joy is separate from price and pedigree, because it belongs to the vast and magnificent world of play.”

The greatest designer of costume jewelry was Kenneth Jay Lane, who died in 2017. His career spanned some 50 years, and though he was beloved by designers, they wanted him for his style, not for a reflection of theirs. He created in every mode and material, from glass beads for a traveling version of Marella Agnelli’s ropes of rubies and emeralds, to big fake pearls for Barbara Bush, to Berber coin belts, Byzantine crosses, Maltese crosses, Catholic crosses, Moroccan fringes, Art Deco hard angles, enameled bracelets, mythological beasts—and everything he made hewed to a central harmony, whether it was from his own imagination or nicely borrowed from those who worked in precious metals. You can still buy his joyous designs, some of which date back to the ‘60s, made exactly as they first were.

The book he did for Harry Abrams in 1996 was called Faking It and printed in Japan, so the photographs are perfectly reproduced.

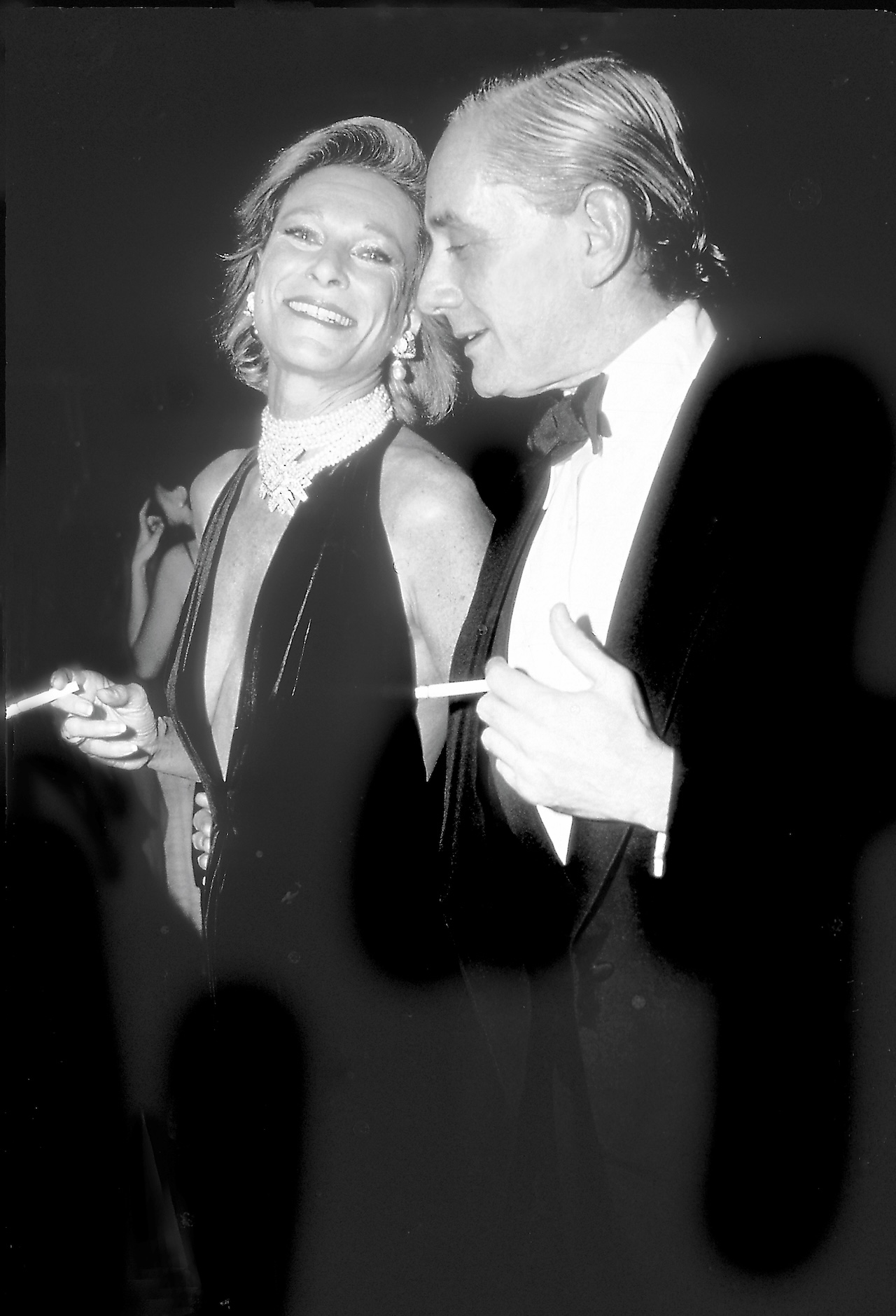

The stories he tells about movie stars and socialites have aged well, because the faker tells the truth, and two stories about Babe Paley show his appreciation of glitter and his respect for the real thing. Babe Paley, who was portrayed by Naomi Watts on TV this year in Capote Vs. The Swans, was the stylish and fabulously wealthy wife of the head of CBS, Bill Paley.

Kenneth Jay Lane writes about going to dinner at her house to see that “one arm was covered with skinny rhinestone bangles that she had bought for a dollar each at Alexander’s.” The look, he writes, “was smashing.” On the other hand, when he realized she had brought “three of the most magnificent Pre-Columbian gold pectorals” he’d ever seen into his showroom to be strung up into a necklace, he sent them back to her and asked her to please never do that again.

The master of fakes knew that you don’t interfere with the real, the precious, the historic.