News feed

You will know a Sibella Court interior by the sudden desire to excavate that it provokes. For Court, an interior stylist, author and the founder of the homewares stores The Society Inc., training as a stylist working in temporary spaces for the purposes of photography put her in good stead for a career that’s now partly concerned with shaping the landscape of permanent spaces, each of which is gilded with a singular detailed top layer that is unmistakably hers.

“It’s intuitive and then it’s fine-tuned,” says Court, whose magic lies in the art of assemblage of disparate objects and who excels in creating cinematic vignettes for viewers to immerse themselves in. Where you or I might look at the flotsam of our lives and see abject and discordant clutter, Court instead sees the potent ingredients for narrative storytelling of the kind that is steeped in sentiment and nostalgia. By Court’s reckoning, the collections of objects that we surround ourselves with are incredibly powerful; their arrangements, then, are a reflection of our world in miniature.

“I am a great collector,” Court said at a recent preview of the 2018 Rigg Design Prize at NGV Australia’s Ian Potter Centre. “I inherit things that are heirloom pieces, I collect vintage pieces, and then I’m into modern design. That arrangement of those pieces [is] overlaid with what I think of as a 3D life story through objects.

A triennial initiative, the Rigg Design Prize is the first major presentation of contemporary interior design in the National Gallery of Victoria’s history, and, perhaps more broadly, in Australia. This year, the invitational competition tasked 10 of the country’s eminent interior designers with responding to the theme of ‘domestic living’. In practical terms, it was a remit that required they fashion from the ground up a single bespoke, purpose-built example of interior design, which, as a proposition for new modes of living, is a practice distinct from interior architecture and acknowledges that great spaces are indispensable to creative cultures that respond, in the most pragmatic way, to human needs.

As new developments in our cultural spaces demand a greater understanding of spatial experience and how our environments directly impact on our experience of life in myriad ways, an initiative like the Rigg Design Prize has never felt more pertinent. Then there’s the fact that, in our hyper-saturated, image-driven, design-savvy age of Insta gratification, where trends have become both increasingly potent and prone to shorter lifespans, innovations in design built to withstand the whims of fashion have never felt more vital.

Each of the submissions to this year’s Rigg Design Prize contained a world therein. Impossibly dense and oftentimes deeply personal, the groundbreaking showcase is an energising display of the industry’s extraordinarily diverse talents. There isn’t a single entry that you wouldn’t risk a lifetime ban from the gallery for if only for the chance to cross the threshold and explore the multitudes contained within.

This felt particularly true of Imaginarium, Court’s painterly design scheme entered into the Rigg Design Prize. The litany of worlds that Court was able to build within the space of 40 square metres was nothing short of astonishing. For fans of her distinctive aesthetic, however, it should come as no surprise.

“This is for any of the guests or visitors who are looking in,” Court said. “They can recognise something that they have and take that notion home of how to display something because all those objects hold a story and an emotion – a shared content where people say, ‘What’s that?’ and you can say where you were, who you were with and at what time you were in your life. Even though that’s an unseen emotion, if you walk into a space that’s full of those stories and emotions, it’s a very rich space to be in. I think that’s where nostalgia comes in, because when people do look at a space like this there is something recognisable; there’s something of, ‘I could do that. I have a vintage piece like that [and] I could layer it’. It’s immersive.

“If you take one idea home for your house,” Court later said, “I would be happy with that.”

Court’s design scheme Imaginarium took its cues from a phenomenon of sixteenth century Europe. Started during a period of history now known as the Age of Discovery, the exhaustive private collections that were amassed would later become the foundations of many of the world’s great museums, many of which are beloved by Court. “It’s also one of my favourite times in history when the world wasn’t as small as it is now,” Court said of the period that has deeply influenced her. “It was still getting discovered and wonders of the natural world – and the unnatural world – were being brought back from long, seafaring trips. Some people would be away for up to five years and they would come back with these items and objects that they have never seen before. That curiosity and awe of things that had never been seen has always stuck with me because I love to keep the curiosity forever.”

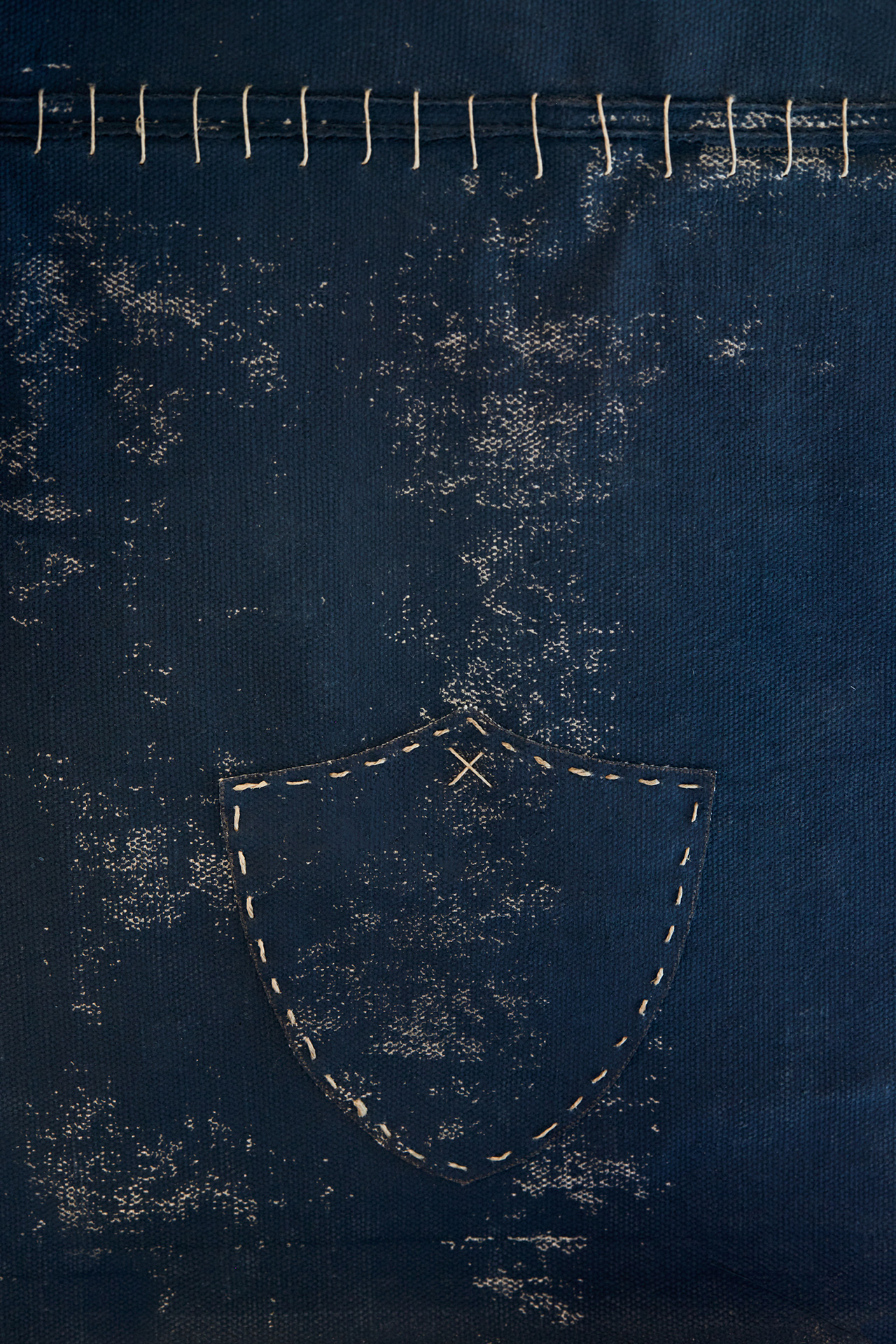

Over time, those collections became more refined and curated, evolving from expansive rooms into precise cabinets dubbed Kunstkabinett, Wunderkammer or ‘Cabinets of Curiosities’. Curiosity is an essential component of Imaginarium. It’s also the inscription in Court’s latest book of the same name, Imaginarium: ‘Stay curious’. The sheer volume of her design scheme provokes within its viewer a desire to explore its elements across a number of senses. Court created a soundscape with the sound designer Benjamin Walbrook to capture not only the sounds of the room but the sounds of the objects contained therein: how they were made, where they came from and their history. A sample included: a child panting, rain falling on a tin roof, the strains of a wizened crooner, the whirring of invisible mechanics and a kettle’s whistle nearing its crescendo. Another vignette, this time tactile, echoed Court’s aural sensibilities with a musical artwork by Joshua Yeldham, beneath which sits Faye Toogood’s Roly Poly chair at the head of a custom Ilse Crawford carved 3.4 metre wooden table from Hub, a lamp from Moda Piera and a Gravity table by the Double Rainbouu designer Toby Jones – all of which was set against the backdrop of a hand-stitched canvas wall painted in a deep blue shade of ‘Boro 2’ from Court’s paint range with Murobond paint. Nearby, a vintage kimono and a graphic sculpture of a barn owl appeared to be lifted from Court’s own home. The installation also featured an alchemy workshop, described by Court as the ultimate place to create, concealed by a curved zinc and steel vestibule made by Saul Forge that channelled Court’s interest in the alchemy of rare earth minerals and pigments.

“To have those objects […] harks back to a time when objects weren’t institutionalised, they weren’t behind glass or necessarily in cabinets,” said Court. “There were tables for show and tell, and I think a big part of all my interiors is ‘show and tell’ where conversation is encouraged and no one is on an iPad.”

THE RIGG DESIGN PRIZE IS EXHIBITING AT THE IAN POTTER CENTRE: NGV AUSTRALIA AT FEDERATION SQUARE UNTIL FEBRUARY 24, 2019. ENTRY IS FREE. MORE INFORMATION IS AVAILABLE HERE.

Tile and cover image: Sharyn Cairns