News feed

Though they first went into business together as a means to fund their respective fine art practices, no such distinction between art and commerce exists for the artists Louise Olsen and Stephen Ormandy. The co-founders of Dinosaur Designs – which began as a market stall and has grown into one of Australia’s most successful design enterprises – have lived and worked alongside one another for over three decades, a feat that is celebrated in a new survey that includes over 50 works in a variety of mediums that speak to the symbiotic nature of their constantly evolving practices, both shared and individual alike.

These works, many of them recent and created both in conjunction and solus, are the subject of Olsen Ormandy: A Creative Force, exhibiting at the Newcastle Art Gallery until February 17. Below, Olsen and Ormandy reflect at-length on their partner’s creative process, their work with Dinosaur Designs, their careers and the reality of life as one half of an incredibly creative coupling.

GRAZIA: You met while studying at art school, before establishing dinosaur designs as a way to supplement your artistic practice. what do you remember of the other’s individual practice?

Louise Olsen: Steve’s always had a great, larger-than-life approach to his work. He’d always have a big canvas going and was working in a surreal world, listening to and writing a lot of music, which was fuelling what he was painting.

Stephen Ormandy: Louise was ahead of the game. She arrived at art school having studied art at Hornsby TAFE and was streets ahead of everybody in terms of sophistication, art language and art application. This was also influenced by her home life [Olsen is the daughter of the renowned Australian artist, John Olsen].

Have you noticed any phases that your partner has gone through over the course of their practice – Any short-lived experimentations in style, technique or genre that were, in retrospect, perhaps a little misguided?

Ormandy: No, I don’t think that there’s anything that’s ever misguided. I think that not everything is a success, but at the same time that learning process is invaluable and you have to have to go through it. The idea of something being misguided – I think if that’s another word for not successful, then yes, we’ve had plenty of things that aren’t successful. But on the back of that failure comes the next step in the learning process, which allows you to produce something that lives up to your expectations.

Olsen: Yes, I mean there’s so much discovery in things not working; such great opportunities, but you have to have to have the courage and take the risk.

Is it at all possible to pinpoint a moment when your partner effectively hit their stride within their practice? Perhaps a body of work, an exhibition, an unexpected flourish that signified a moment of considerable growth?

Olsen: When Steve had his first solo show at the Tim Olsen Gallery in 2008. That was a major shift in perception of him as an artist.

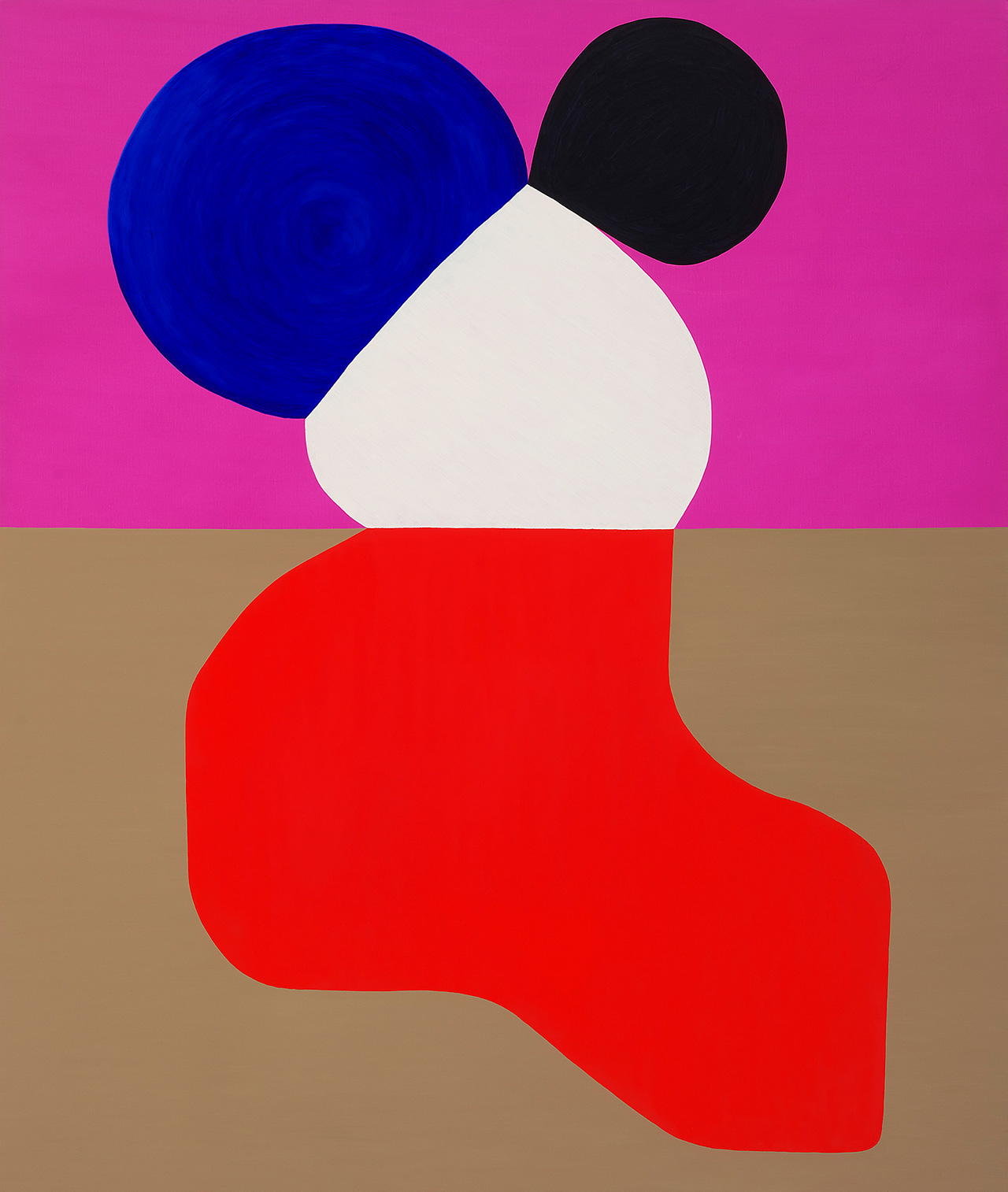

Ormandy: In terms of a joint work, being asked to create a work for GoMA in Brisbane was a significant moment for us in terms of our creative collaboration. That was a moment where we used the core values of Dinosaur Designs but stepped outside of it, scaled up to gallery proportions and produced a series of platters together [Series 8]. I think Louise has always been very consistent, but I think for her especially, just getting back to painting after many years of focus on many different pieces of art, especially creating work for Dinosaur Designs and jewellery collections under her own name. But stepping back onto the canvas, as it were, has been a big moment for Louise. And that’s very recent. Her new works on canvas are so good they look like she’s always been painting, but she’s always kept her sketch book going and has always done life drawing.

Olsen: But in retrospect, there have been so many milestones over 30 years, and each one has helped build to where we are now. But GoMA was quite a big one, and what’s great is that exhibition led to us having an exhibition in Bega, which led to Hazlehurst, which then led to us having this exhibition in Newcastle and this great opportunity.

Your works on canvas and your sculptural works are very distinct from one another, as they are from your work with Dinosaur Designs. How would you describe your partner’s art practice to someone who had never seen it before? Conversely, how would you describe the works resulting from your own practice?

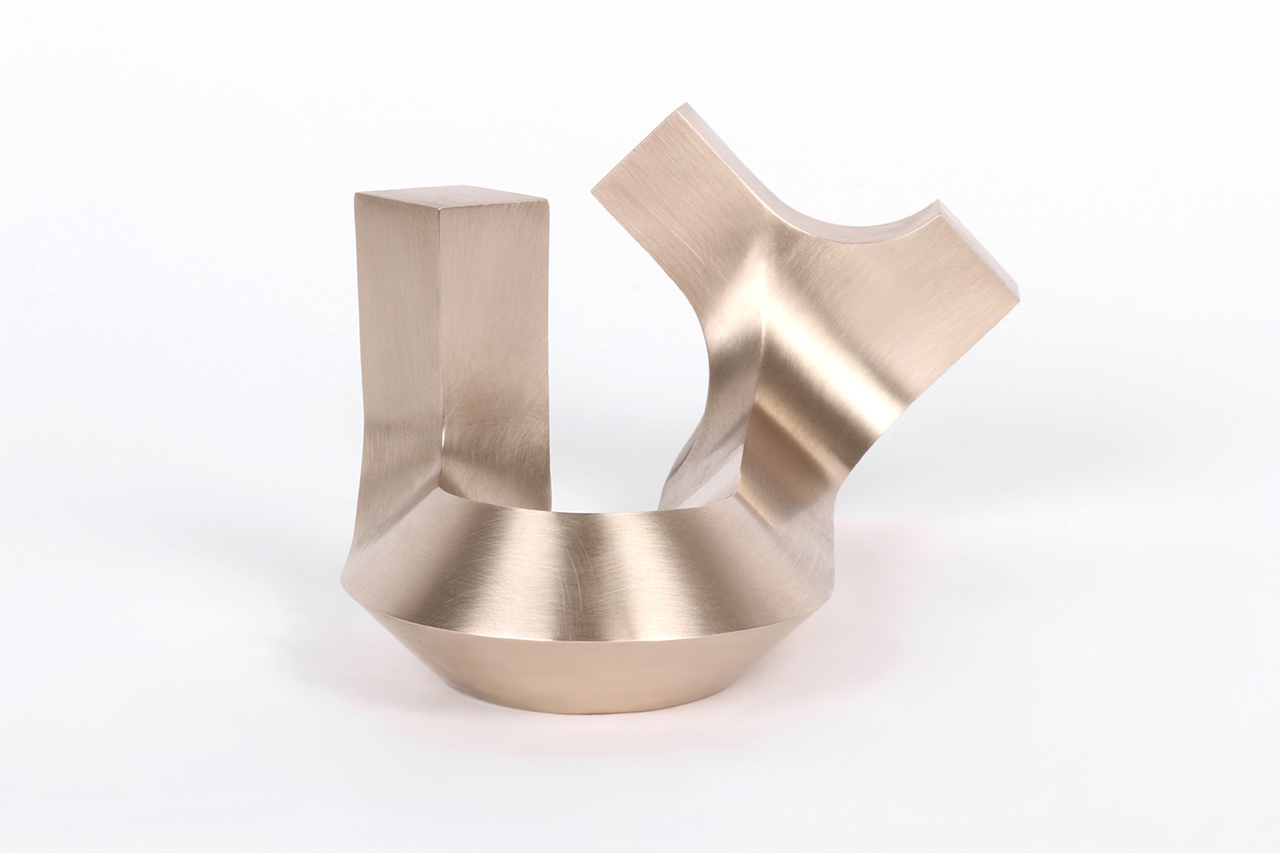

Ormandy: Our work within Dinosaur Designs shares a core language and then we both have distinct styles within our own art practice, but there are crossovers; I mean just look at the totems that I’m producing – they’re artworks that grew from a design experiment for a collection at Dinosaur Designs, which then grew into a sculptural experiment. We view our work at Dinosaur Designs equally with the way we view our art; it’s a sculptural process and we apply the same rigour whether we’re creating a bead or a creating a sculpture for a gallery or making a bangle or a necklace.

Olsen: I think being an artist is about exploring the material, discovering what it can do and then pushing the limits of what you think it can do and the results not just limited to being ‘design’ or ‘art’. The distinction between what’s considered design and what’s art is relatively recent. [Alexander] Calder created beautiful jewellery and sculptures; [Pablo] Picasso created beautiful paintings, ceramics, jewellery and sculptures; [Alberto] Giacometti created wonderful sculptures and a collection of homewares with his brother.

Ormandy: We created Dinosaur Designs to fund our art practice, but in that process we couldn’t divorce our ‘art’ selves from the other work we were doing. It’s not as if we suddenly thought ‘let’s put on a design hat’. What we thought was, ‘let’s use our creative abilities and make something that’s more immediate’. So we went to the markets having made something that was sellable in that environment as opposed to an austere art gallery.

I think Louise’s painting is very fluid. It’s got this lovely lyrical fluidity to it. Literally the paints are flowing and moving and she moves them around the canvas, tilting it, lying it flat, lifting it back to the vertical and bringing it back to flat in addition to working with the brush. It’s a very interesting, very deliberate and controlled process and the results are beautiful. There’s a wonderful serendipity to it.

Olsen: Steve’s work is very colourful, geometric and plays around with forms, shapes and structural, interconnecting planes, but there’s also a playfulness to it that gives it a life force.

Removed from the context of dinosaur designs, What similarities do you see between each of your individual practices?

Ormandy: Each of our practices are very intertwined; there’s so many similar ways that we work so certainly there are similar processes and influences. We love the same things, we travel and we look at things and find things we love. It’s just a natural thing to do.

Olsen: We share a sense of colour and a certain sense of structure. Even though it’s different, there’s a point where we meet.

Ormandy: Looking for strength of composition is very important to the way that we both work, there’s this balance in the work that has a solid basis to it. It talks about the history of art, of all the artists we’ve loved and seen. I think there are moments that come through from that.

When you witness your partner at work, how are they transformed? Are there any rituals they practice, quirks they inhabit or conditions they like to replicate?

Olsen: Music. Steve loves listening to music with his coffee. There will usually be a very loud disco beat that pervades the studio when he’s painting. And he’s usually wearing his favourite old runners and painting pants. They’re so covered in splashes of paint they’re almost an artwork in themselves. But with the music and the coffee and the pants and the runners, he goes into a trance-like state.

Ormandy: Louise has been painting down in the Southern Highlands. Sometimes she has music on, but then she’s just as likely to be listening to the music from the birds outside or watching the movement of the lake. She’ll often take time to dream and meditate and that comes through in her work; there’s a real freedom to it that’s underpinned by a great sense of control.

How do you see your partner as having pushed you to work harder or forge new ground in your own practice? What effect has their encouragement and support had on your attitude to your own creative output?

Olsen: I think we’re very exacting with each other. We’re very encouraging, even though we both work in different ways. Steve’s got a great driving force when it comes to his art and in many ways he doesn’t need much encouragement. But we do question and challenge each other; we tell each other what we think and we talk about it.

Ormandy: It’s not as if I need encouragement, I’m just off doing it, I’m driven. Louise has needed some encouragement in some areas. I think she’s let her painting take a back seat. It was always in the background, but it wasn’t actually being solidified into works but this exhibition’s brought that back. It’s a big step to paint too and to put yourself out there, to put it up on it up on the wall.

Olsen: I think it has definitely been percolating and the timing was right. My dad’s also been incredibly encouraging to me as well and gave me a space to paint. When it came to painting again, I just realised how much I’d been putting all my creativity into Dinosaur Designs and putting my own painting on the back shelf.

What is your attitude to feedback from your partner? Is their perspective always welcome, or does it sometimes pose an impediment to your process?

Ormandy: It’s always welcome, whether or not you like hearing what your partner says about your work, because we both have a respect for each other’s opinion. Even when we think what they’re saying is wrong, we can’t dismiss it out of hand. You can’t just say ‘OK you’re wrong’ and walk off. It makes you stop and think ‘What are they seeing that I’m not?’ We take it seriously. Sometimes we agree and come around, see what they’re saying and other times we don’t – it just depends. But we both respect one another’s visual opinion, that’s for sure. It’s great to have a foil, to have someone who understands art and can give feedback that you trust. If Louise likes it, it’s a moment of ‘yippee!’ I feel really good. That’s the greatest encouragement.

This new exhibition, OLSEN ORMANDY: A Creative Force, includes new work from both sides of the partnership, from Dinosaur Designs, and also includes new work made in collaboration with one another. what was the impetus behind the creation of those select joint works?

Olsen: We have a mobile that we called Magpie, which came from a resin paddle form Steve created for a different piece and I asked for it to be cast in black and white and it became like bird feathers.

Ormandy: It became an expression of a magpie. Louise has talked of how she wanted the white and the black to meld. Sometimes it was a clean line, sometimes it was a beautiful mottled effect as if the colours were percolating together. So this is very interesting play of dark and light, yin and yang; of balance. Then we worked on the hanging together and how we should construct it. We went through multiple ideas and eventually decided to hang it from a single rope in a circular construction. That seemed to work really well.

Olsen: We were playing with black and white forms, and it grew to resemble a magpie circling that you can circle as well; it has these weird shapes that fly out of the sculpture.

Ormandy: Magpies are a big image in Australia; they’re a big part of the landscape. It’s a powerful bird. We all know about swooping season and kids riding to school with an empty ice-cream container, with eyes painted on it, on your head. That’s what we grew up with as kids. You’d always have an ice cream bucket on your head during swooping season. The black and white instantly talked to that idea and gave it a lovely grounding. So, I’ve had a more physical input on shape and hanging and Louise was more lyrical in terms of colour and form. It’s not as if it was an in-depth collaboration that went on for hours and hours. It was fairly swift.

Olsen: We’ve been working together for over thirty years so a lot of our collaborations are put together quite quickly. We don’t have in-depth meetings and discussions, it just happens. We share a visual language and many points of reference, it’s a very fluid process.

Ormandy: The conversation tends to be ‘What do you think of this?’ and I’m hanging it in a particular way. The first hanging didn’t work – we both agreed it looked crap so we pulled it down and worked on it a bit more and then we both loved it. So, in a way, it was easy, but that sense of ease has been developing for over thirty years.

When you do work together to create a single work of fine art, what is the division of labour like in a practical sense? Would you say your partner has certain technical strengths that you don’t possess yourself?

Olsen: Definitely. Right from the very beginning Steve knew so much about resin because he was a surfer; he was the one that got all the technical aspects of working with resin together, which really enabled us to get the business going. He loves a toolbox, the nuts and bolts. He’s great at that, he’s always loved Lego and Meccano; Steve invented the machinery we use. When we first started working with resin, there was really no one we could call to discuss how to use it, so although we’d worked with it at art school, our technical skills were at a pretty low level. Steve really put his head down and figured out to work with it. He’s always been the nuts and bolts person right from the very start. I had a body of experience of drawing and painting that I could draw on that was very different from Steve’s. He was also very creative, but he also had an interest in making things and understanding the technical aspects at a very in-depth level. I love making things but I’m not as process driven as Steve – he’s very good at the chemistry and perfected it to the point where we use it today.

Ormandy: The outcome benefited both of us in that it enabled us to articulate our ideas and build a product that was of high quality. Resin is a material that’s very difficult to work with and you have to get the technical aspects right.

In what ways does your partner’s work continue to inspire you? How do you hope to see their practice evolve and grow over the next thirty years?

: I think that both of us just want to continue to enjoy doing what we’re doing. Evolution looks after itself. If you have a love of making and creating then that process is just a joy. And what happens is that, as you go through life you’re like a tree; you’re a little sapling in the beginning, this tiny little thing and you bend and blow in the breeze but then as you grow you get more multifaceted, you get more branches and more leaves and you just naturally turn into a big thing, then suddenly people look at you, especially young people looking at someone who’s more established, and they think ‘Wow! How did they get there?’ Well, for us, we just kept going, we didn’t stop, didn’t fall over or get run over, we just kept going. And that’s where we’re at now and it’s inevitable that our practice will grow as long as we’re practicing. It just keeps evolving.

Olsen Ormandy: A Creative Force will exhibit at Newcastle art gallery until february 17, 2019. more information is available here.

Tile and cover image: Courtesy of the artist