News feed

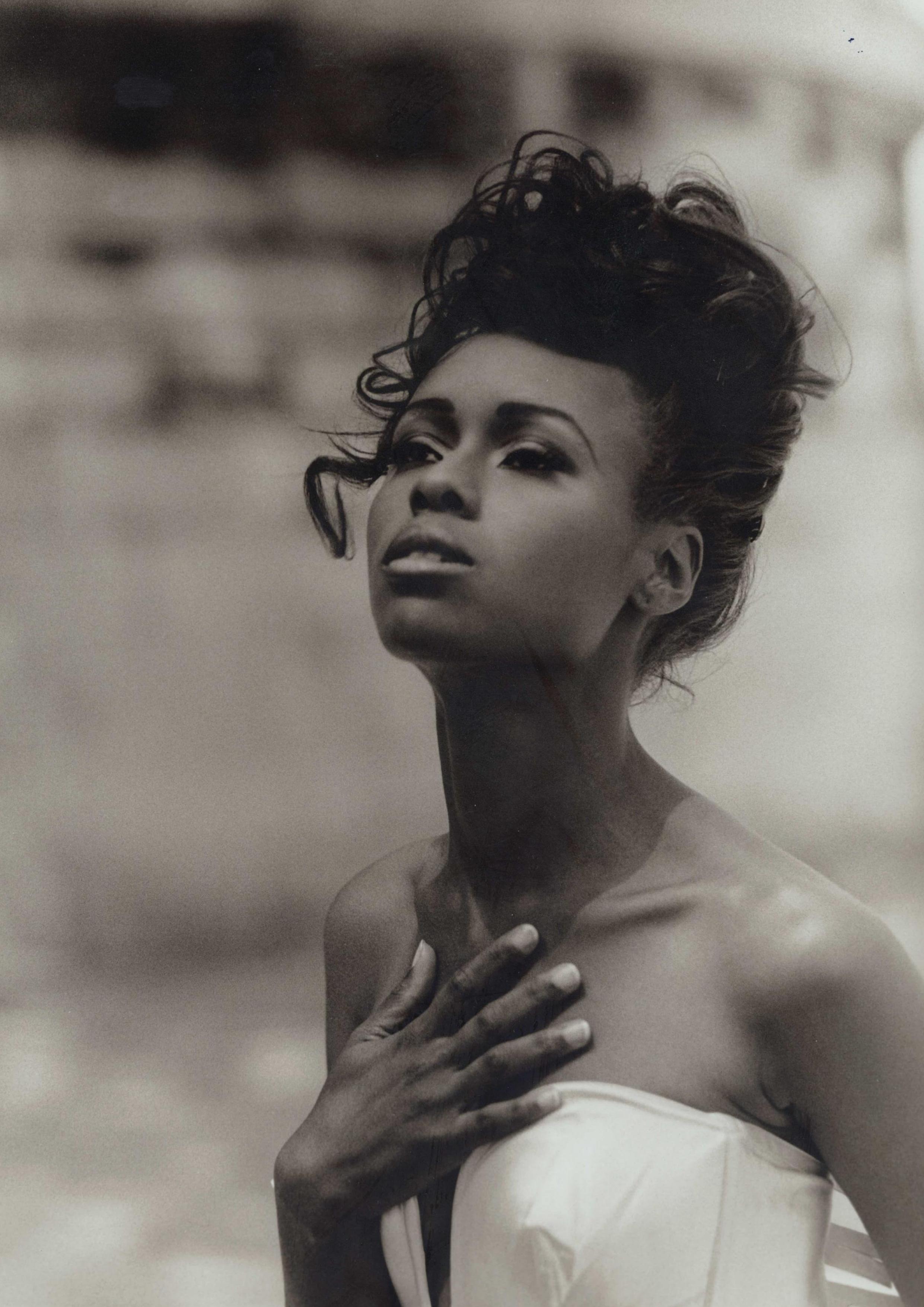

“When you were laying on the sidewalk – face down, zip-tied – did you fear for your life?” I ask Charmaine King, a 55-year-old American event producer living and working in the fashion industry in Paris.

“Yes. Absolutely,” she replies assertively, the beautiful wide smile that she had greeted me with just moments earlier now a pursed red lip. “It’s an ongoing conversation that Black parents have with their children about how to behave, not if you are stopped by the police, but when you are stopped by the police. Because it is going to happen – and you need to come home alive.”

The year was 1985 and King, then just 19 years old, was walking back to work from an LA grocery store when she was approached by white police officers. For no reason other than the colour of her skin, King was forced to lace her hands behind her head and lay down on the ground. While officers checked her identification, one had his foot firmly planted on her neck.

As the George Floyd murder trial plays out in a court right now, King’s story is an important one to share. On May 25 2020, 46-year-old Floyd – a Black man from Houston, Texas – was killed when a Minneapolis police officer stood on his neck for eight minutes and 46 seconds. “I can’t breathe”, Floyd pleaded. “Please.” He lost consciousness and was later pronounced dead.

“This is not the first time and it surely won’t be the last time,” says King.

While a strikingly similar incident is recounted by King below, what precedes this moment is a lifetime of casual and overt racism. Ahead, the event producer denotes a timeline in the “discovery of her Blackness”, the moment she feared for her life, and her note on the importance of being educated and being kind.

If there is one thing you should read today, make it this.

GRAZIA: Growing up, how confident were you as a young Black woman?

CHARMAINE KING: I was confident in my ability to do things. I was not so confident in the fact that people wouldn’t let me get to where I was going. I was always comfortable being Black. I had the absolute fortune of being a first-generation American so I think that that colours a little differently how you view yourself and the level of confidence that you are given through the prism of education that you receive. My parents are both from the West Indies, both from Trinidad, so my experience is a little bit different from being generationally Black American. It was never a thing for me to be Black. It was always the view of someone else that made it uncomfortable.

GRAZIA: When you were 11 years old, an incident happened where a boy in your class likened the colour of your skin to “mud”. Can you tell me about that moment?

KING: We were in Keene, New Hampshire that summer which is North East of the United States. My mother had met this man and because we were there, she was like, ‘You should go to camp, what else are you going to do other than hang around here?’ She enrolled me in summer camp, and I was doing all the things that normal kids do – you hang out, you play, you learn how to make macrame which serves absolutely no purpose but you’re learning something new! I was having a really good time. As we weren’t rich, it was actually the first time I got to go to summer camp. I had a place to be. I got to do normal stuff! One day, a bunch of us were playing and this little boy said to me, “God must hate you”. I said, “Why?” and he said, “Because he made you Black like mud.”

GRAZIA: How did that make you feel?

KING: “I was super hurt. I couldn’t let him know that he’d hurt me though. Children are cruel but I knew that if I let him know that he had really, really hurt me, that that would be the point that he would press. I finished out the day, I went home and I cried. I couldn’t tell my mother what happened for about two or three days. Of course she was furious when she found out. I said, ‘Mum, let it go. If you pursue this, it will just make it worse for me. I’ll ignore him. This will be over and I’ll keep it moving.”

GRAZIA: What was your mother’s response to that?

KING: She was furious but she told me like she had always done, “You are bright, kind and intelligent and it doesn’t matter what anybody thinks of you.” By the time I was 12, I had literally stopped caring about what anybody thought about me. I had to keep it moving. By that age, I was at boarding school in London. I was the only Black border and one of two Black students. You just have to figure out your life. I believe there is an actual timeline in the discovery of your Blackness in relation to who you are. The first moment is when you’re about four or five and you’ve played with other kids. Around that age you realise you’re not the same colour because someone makes you notice that you’re not. Then, around the age of 11 or 12, someone makes you realise your Blackness is not a good thing. It is an actual negative. The final part of that timeline comes in your teen years. You will have a traumatic experience related to your colour. It could be a beat down or your first stop-and-search by the police.

GRAZIA: Tell me what happened that one specific afternoon in 1985 when you set off to get your groceries.

KING: I had just moved to California and I got this job working for a female director in Brentwood. I realised rather rapidly that it wasn’t going to be a good fit. I told her that morning that I would work out the rest of the day but I wouldn’t be returning the following day. In America, that’s not that big of a deal. She was not a nice woman.

GRAZIA: What happened next?

KING: She asked me to do the shopping for her so I walked to the grocery store and as I was walking back I hear the “woop, woop, woop” – the police siren noises – and I was surrounded by three squad cars. They had a megaphone telling me to drop the bags and to get on my knees and put my hands behind my head. I was freaking out. I was 19 years old, I weighed nothing. I was a skinny kid. I put the bags down, I got on my knees and laced my hands behind my head because we’ve all had those conversations with our parents when you are pulled over the police. We have these conversations because your parents want you to come home to them alive.

I’m shaking. I knew I hadn’t done anything wrong. One of the officers – a white man – he takes my hands from behind my head and zip ties me, he used riot cuffs. He pushes me down on the ground. I’m flat on the ground and I have my head to one side, obviously. And then he put his foot on my neck. He is literally standing on me.

I asked him, “Why am I being detained? What did I do?” He said there had been a spate of robberies in the neighbourhood. I said I had literally just got to California, it couldn’t be me. He asked me where my ID was. My Florida driver’s license was in my handbag. I told him it was inside the zip pocket and he can take it out. It took forever. Well, it seemed like forever. I said, “If you’re going to arrest me, just arrest me. Take me away but don’t do this.”

GRAZIA: Was his foot still there?

KING: Yes. He never took his foot off my neck. There’s about six or seven officers around me – one is in my purse, one is in the squad car calling me in. I was just terrified because my mum was picking me up from work at the end of the day, and I knew that if she saw me hand-cuffed on the ground, she would lose it. And if that happened, they would shoot her for making motions and then probably shoot me as well and make up some bullshit. After discovering I had no criminal record, they cut the zip ties and rolled out. They literally left me there. I was shaking. I picked up the bags and walked the rest of the way back. I never even went inside. I put the groceries at my employer’s door and sat on the front step and cried until my mum came to get me.

GRAZIA: And nobody helped you up off the ground?

KING: No. I was one of only a few Black people in Brentwood. It was 1985, there were no Black people in Brentwood. Anybody who witnessed it was probably terrified.

GRAZIA: Let’s go back to that moment on the sidewalk. When you were there – face down, zip tied – did you fear for your life?

KING: Yes. Absolutely. It’s an ongoing conversation that Black parents have with their children about how to behave, not if you are stopped by the police, but when you are stopped by the police. Because it is going to happen. You need to come home alive. You’re taught that if you’re in your car, you must keep both your hands on your steering wheel. You’re taught not to be aggressive and to appear smiley, cheery and non-aggressive. You have to do whatever is necessary because they will find an excuse to take you away.

GRAZIA: Did this incident effect you long term and if so, how?

KING: It did. You realise that no matter how good you are, no matter how smart you are, no matter how much you blend into society, if you make what someone else considers the wrong move, you are then guilty without reason. It colours the way you do everything. It colours the way you walk down the street. It is absolutely annoying that you get on the subway and every old white lady clutches her purse a little bit tighter. It happens all the time.

GRAZIA: Did you watch the video of George Floyd’s death in its entirely?

KING: I did. It made me sick.

GRAZIA: As somebody in this world who has been in a very similar situation, what feelings did that conjure up for you?

KING: So many. The first being absolute fear. I feared for George the way that I feared for myself that day as a 19-year-old. It disgusted me because this incident was not the first time and it surely will not be the last time. I was given the sentiment that nothing will ever change in America. It’s not just America – honestly, these things happen in much less publicised measures everywhere. Why Black people instil fear in the rest of the population… I mean, I get it. We’ve been conditioned to think that Black is not good. Or that it is a threat. Or we are absolutely different and a little bit less than. People feel that the colour of my skin means that I will eventually resort to savagery.

GRAZIA: There are so many things that need to change in the system but what would be at the top of your punch list?

KING: I had a white girlfriend of mine call me up – educated, lovely, lives in France. She was like, “I think I might be racist.” I was like, “OK, you probably are but so is everyone else.” Everyone fears what they don’t know. I told her, “Let’s start with how I am not the authority on all things Black. I can tell you what I think but I can’t speak for an entire race.” From my point of view, the whole thing is about tolerance and lack of knowledge. I said to her, “How about educate yourself and be kind? There’s a host of important books that you can read that might make the difference.”

GRAZIA: Do you think the BLM movement will signify any sort of turning point for Black America?

KING: There’s two things. This is not the first time people have been up in arms. I think this time is different because everybody is locked up in their houses and doesn’t have anything else to do besides focus on this. So perhaps change will happen. But if we are not organised and have actual real demands to Washington, to the Senate, then this doesn’t mean anything. It’s just noise. If we’re not clear on what it is we’re expecting from all of this, then no one has expectations to meet and nothing will come of it.