News feed

Want aLL YOUR FASHION, BEAUTY and CELEBrity NEEDS satisfied?

Click HERE to subscribe to the current + next edition of GRAZIA now.

Receive two print editions a year for $20 / NZ A$50 / International A$80

Better still, collect all THREE of these limited edition EXPLORATION ISSUE covers!

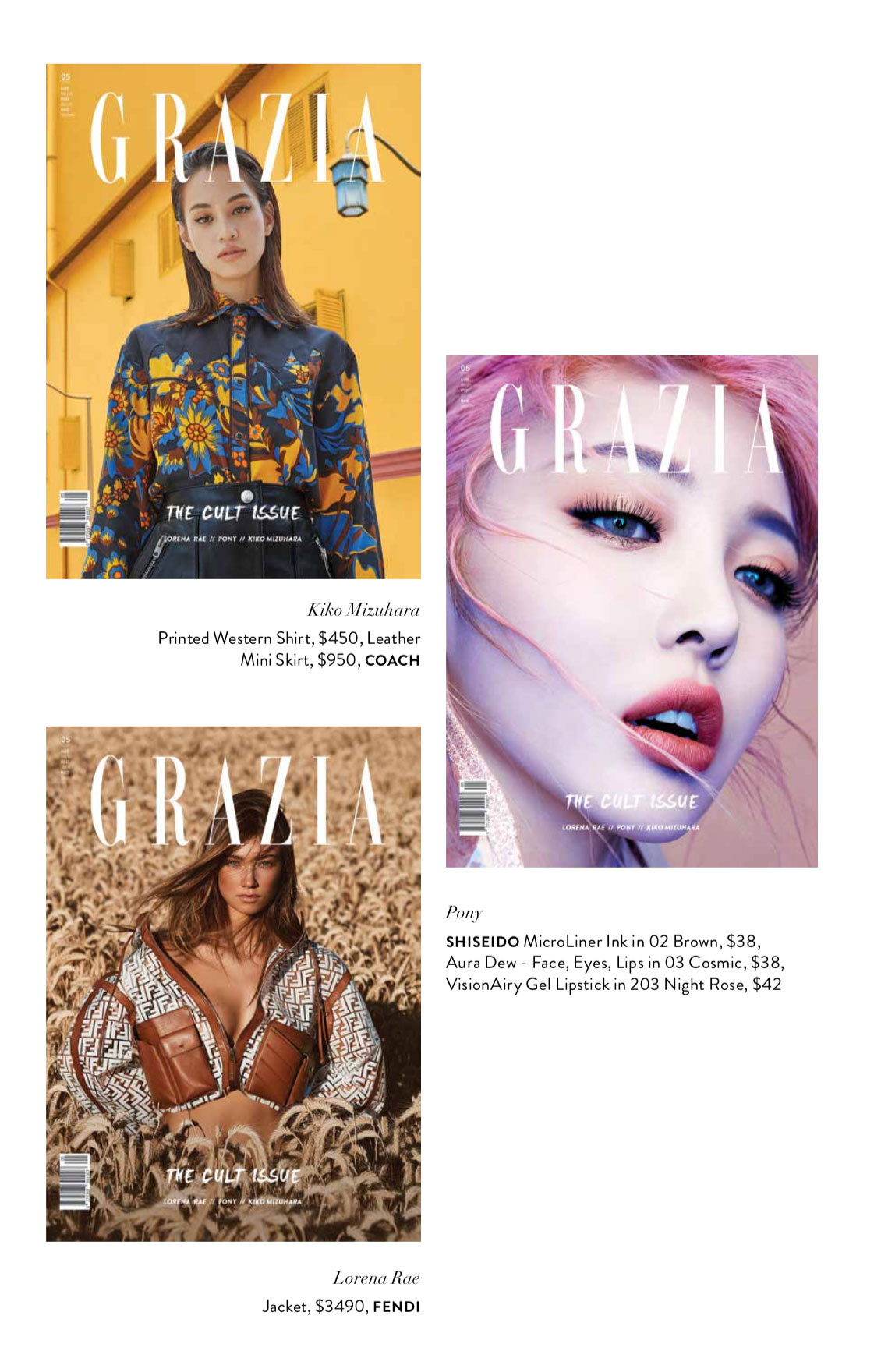

THE CULT ISSUE / 05 / MARCH 2019

“WHEN I SAT UP, HE WAS STANDING OVER ME, AND SECURITY HAD TO ESCORT HIM OUT”

Lorena Rae recounts as we prepared for our fashion shoot (p.118). The model speaks about a man she did not know, who convincingly deceived staff and made his way inside the Dogpound gym in SoHo, New York City. How did he know she was there? How did he know the details he should provide to mask his identity? Lorena had tagged her location on Instagram stories – and her stalker, just like You’s Joe Goldberg (p.208), found her.

This level of excess devotion is common cult-like behaviour, and even if there is less overt street and stranger recruitment into cults today, it is because many now use professional associations, self-help seminars, and the internet as their main recruiting ground. Social networks like Instagram, Facebook groups and YouTube channel chats easily encourage various methods of peer and leadership pressure, and, ironically, in the very nature of free speech the web provides, users often self-renunciate in order to be part of the (greater) group.

The term cult was born from a delineation between a church and a sect, borrowed from the French culte, and the Latin noun cultus, meaning “to worship”. Although academics attempt to dissuade society from identifying a group as a “cult” due to the negative connotations, today the usurpation of the term presents a new positive social-psychological perspective. A cult can be either a sharply bounded social group or a diffusely bounded social movement held together through a shared commitment (generally to a charismatic leader.) It upholds a transcendent ideology (sometimes – but not always – religious in nature) and requires a high level of commitment from its members in words and deeds. For example, eating Nutella from the jar while watching Netflix and texting those who are doing the same. On a nightly basis. In my case, anyway.

Literature has traditionally attempted to control the boundaries of behaviour within a cult, but the rise of feminist dystopian fiction (p.212) affords women the opposite, and instead encourages critical inquiry. Catapulted into mainstream culture by the popular TV series, Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale is now one of many examples reimagining the future of women’s universes – in or outside of systems of control. Whether you take the words of these works as hyperbole or accurate assessment, the protagonists and personalities have audiences that are united by devotion to their allegiance. As does this edition of GRAZIA.

Hye-Min Park, aka PONY (p.170), emphasises special doctrines outside the prescriptive GRWM videos one normally expects from a beauty blogger. Her millions of followers have caught a self-diagnosed “PONY Syndrome” and obsess over her every aegyo eye trick. The systems of influence she commands defy the algorithms of Instagram feeds.

Descent is obviously taboo for a member of a cult yet model Kiko Mizuhara (p.110) is no stranger to a departure from a transcendent belief system. Raised in Eastern Asia, she employs an expression in her creativity that exists outside traditional rules, regulations and sanctions and has seen her collaborate with the likes of Opening Ceremony, Dior and, most recently, Coach. Her fame shot to a new frenzy when Harry Styles recently followed her on Instagram, sparking rumours that the pair were dating, when in fact they’d never even met.

The instantaneous nature of our lives being exposed on social media in real time is challenged by Lorena, who chooses to exist in real time, but now posts days later, letting the algorithm do the work. Echoing her sentiment of a rewarding offline presence, I hope you enjoy this issue.

— MARNE SCHWARTZ