News feed

“All photographs are accurate,” goes the quote attributed to the late, great photographer, Richard Avedon, “none of them are the truth.” For the multidisciplinary artist and photographer Bartolomeo Celestino, all photographs could also be said to be equal – it’s what you do with them, however, that matters most.

“There’s no difference between someone who shoots on incredible 8×10 film, or 4×5 film format, and someone who takes a picture with their phone,” the photographer recently told GRAZIA. “I think it’s [about] your intention and what you produce from those thoughts.” The famous Avedon quote is an apt one to appear as it does on Celestino’s Instagram, best known as a showcase for his sublime, large format stills of the Australian landscape, turbulent white waters redolent of glacial lunarscapes in particular. Not unlike the tempestuous ocean, Celestino too is something of an agitator – perhaps it’s the Gen X in him, he proffers – and not long ago, followers of his feed began seeing an altogether different type of photograph disseminated by the artist. “The idea of constantly wanting to show everyone what you were doing was kind of just ridiculous to me,” Celestino observes of the uncanny mentality underpinning our ceaseless and seemingly interminable engagement with social media. “But I was also fascinated by it. Like, why am I looking at this stuff [when] I could be learning how to speak French?”

So he embarked on something of a radical departure from his regular practice but with a repetitiveness that’s characteristic of his practice, sharing image after image of luxury cars mangled beyond recognition – some still aflame and others wrought into cold, impossibly contorted shapes. “To me, a vehicle is like a camera,” says Celestino. “It’s a utilitarian device. It gets you from A to B. I don’t see the allure to it, outside of it being a tool – that’s just the pragmatic person that I am [and] I took some kind of perverse joy in watching my numbers drop. And people were like, ‘enough with the car crashes, can you please put the sunsets up?'” Not long after he began the social media experiment in earnest, an acquaintance reached out to Celestino, someone who had experienced a loss in a motor vehicle accident and for whom the found photographs were serving as an inadvertent reminder of their trauma. “I thought, ‘Oh wow, this has really affected someone'”, he recalls. “I had to think about how what you can do [with an image] can really affect people.”

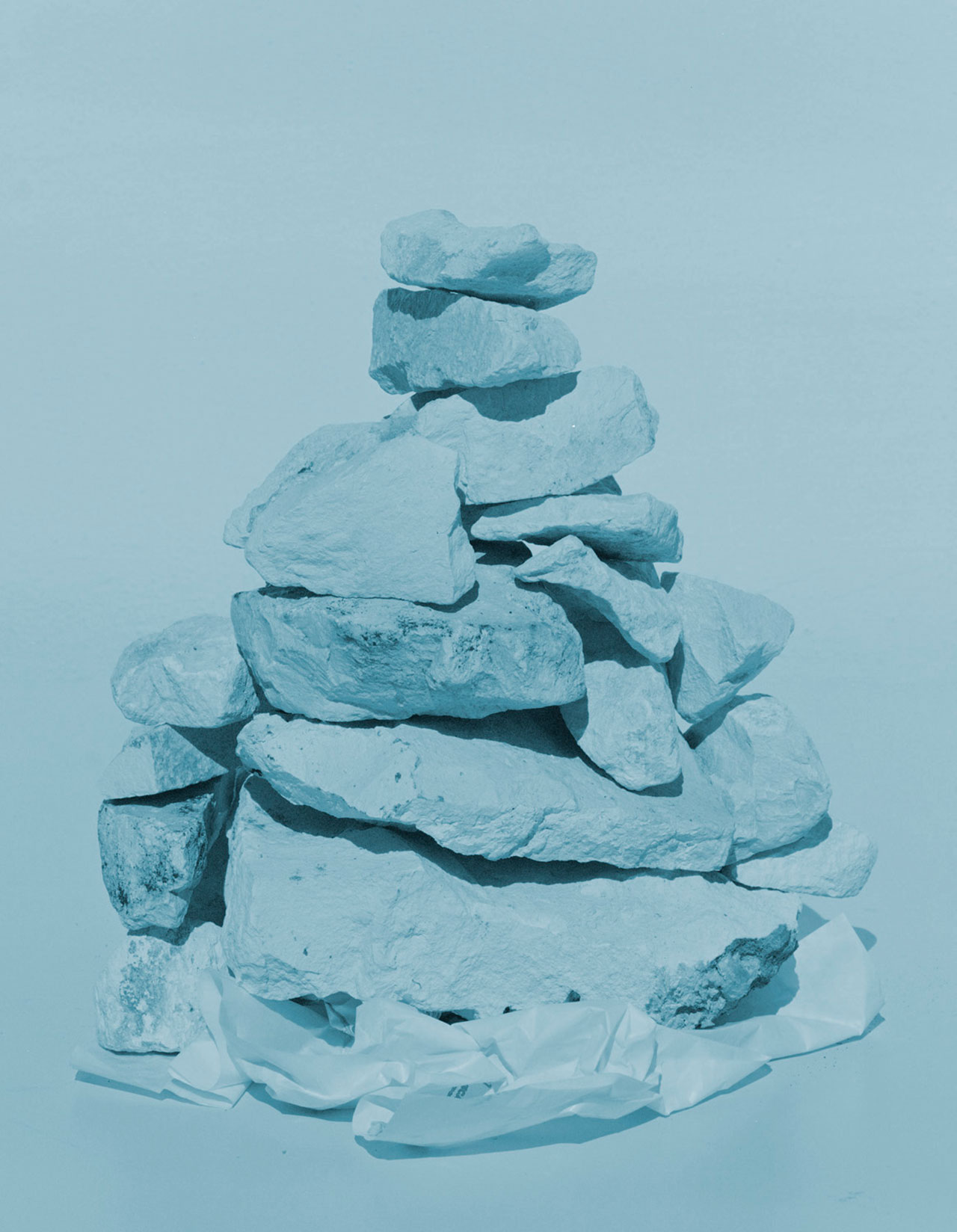

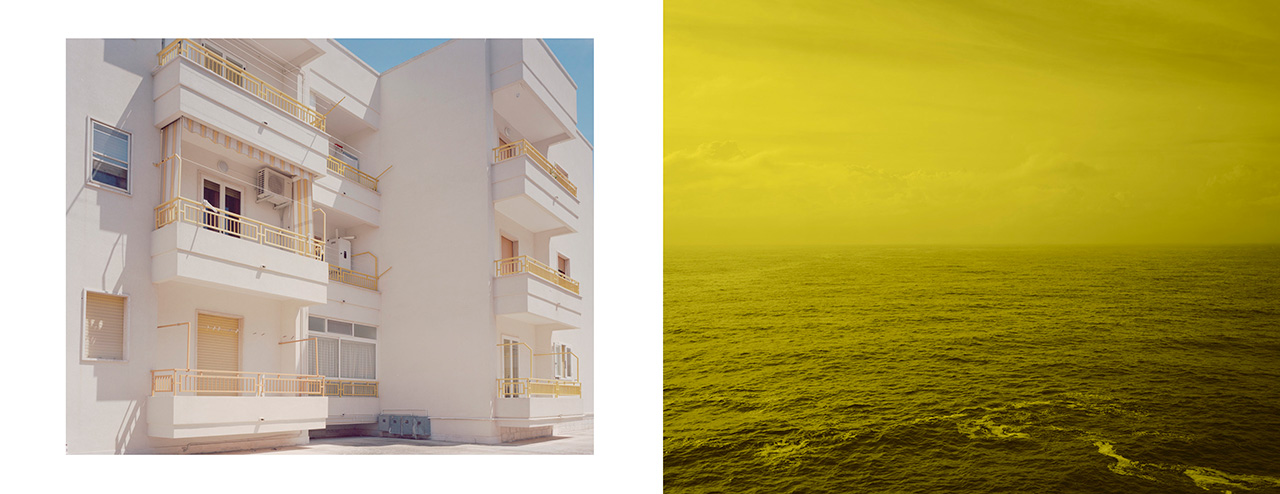

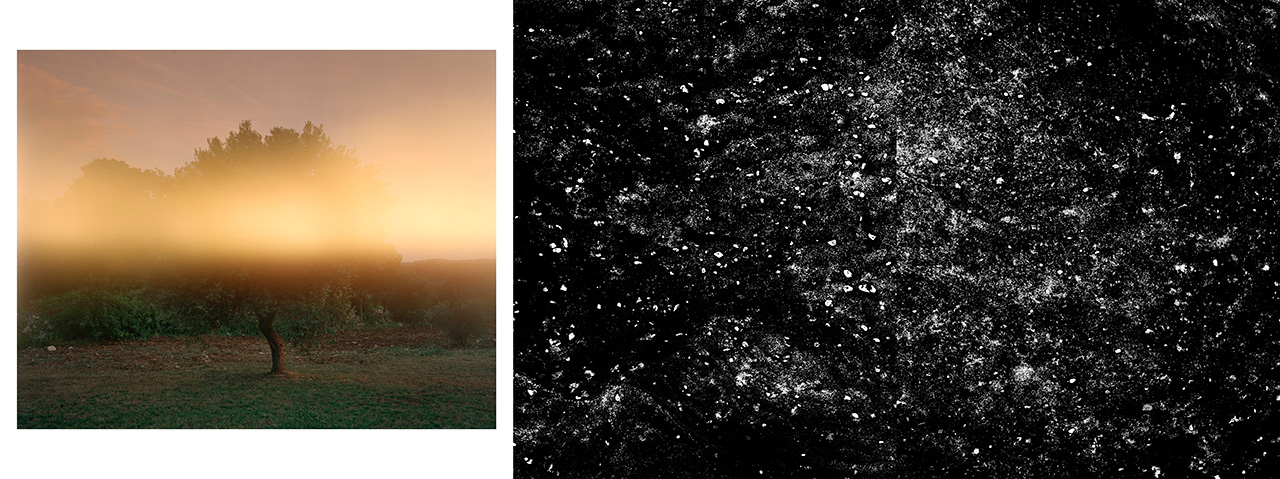

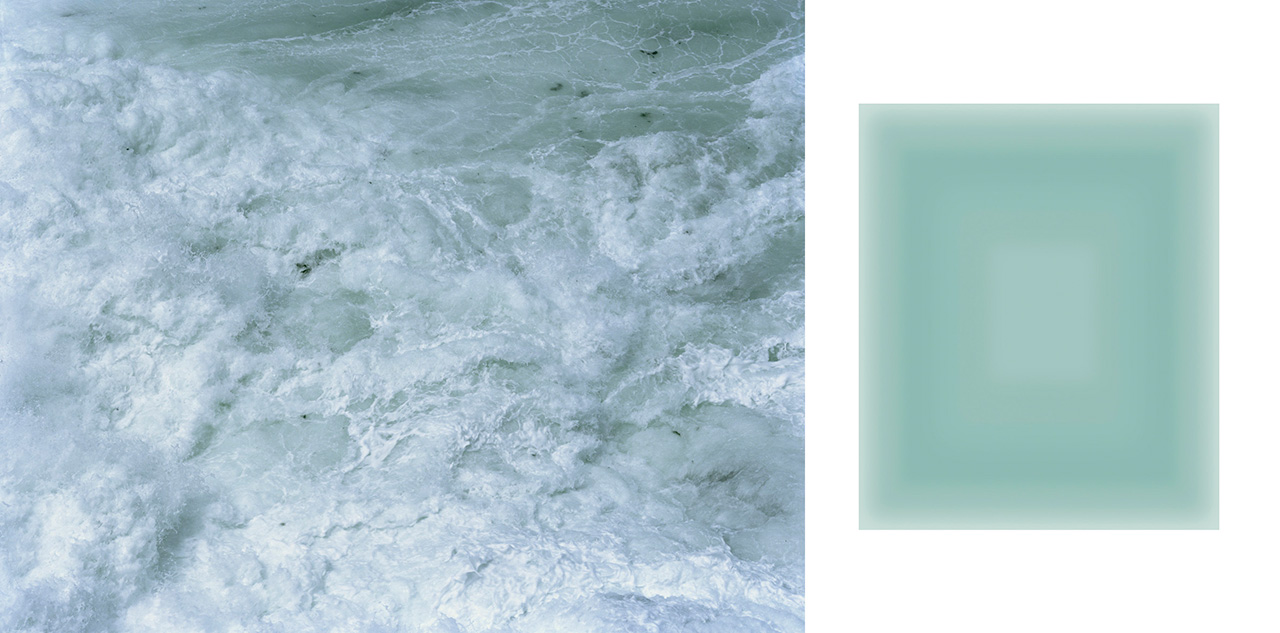

The wreckages have since been cleared, and in their place is a new series of images that the photographer has been sharing for going on two months now: the fragments of a deeply personal new body of work. There are colour field seascapes abstracted on paper to a point entirely beyond recognition. There are the rudimentary memorial cairns fashioned out of chalky, oxidised rock perches atop an ersatz turquoise Mediterranean sea fashioned from blue-green sandwich paper. There are ghostly landscapes emptied by the harsh midday sun or made alien by crepuscular light, and – by popular demand – there is a sunset or two.

Bart Celestino was born to Italian parents in Canberra’s Woden Valley, a sprawling warren of suburban quietude in the city’s south that’s hemmed in on either side by bushland reserves that rise and fall, eventually acquiescing into agreeable hilltops. Growing up, he says he never saw a fence – just grass, earth and space that was traversed on foot or by bus, with ample time allotted for contemplation in between. Nonetheless, it was a hard upbringing, growing up at a time when the sprawling city was still in many ways only aspiring to the kind of cosmopolitan bona fides befitting of its stature as a capital city – a country town reaching for the idealised cultural density that it arguably enjoys today. It’s perhaps not surprising then that he developed a fascination first with graffiti, the unsanctioned artistic medium of disenfranchised youth no matter their geography, and then photographing graffiti splayed across the city’s great swathes of Brutalist concrete. Displaying an industriousness not ordinarily associated with the subculture, Celestino created Damage, a seminal magazine that he says garnered a cult following and piqued his interest in the craft of photography. At 16, Celestino’s family – he is one of three boys – decamped to Melbourne, where a burgeoning interest in a career in photojournalism (war photography in particular, much to the chagrin of his parents) was soon thankfully parlayed into more practical avenues on the advice of the journalist and editor, Marion Hume. As soon as he was old enough, Celestino answered the siren song of fashion photography’s arguable mecca, New York before, post-9/11, moving to Hamburg (“the Paris of Germany”) to work as an assistant for fashion, landscape and commercial photographers. It wasn’t until he met his wife, the photographer Bec Parsons (with whom he also co-founded the biannual fashion title Love Want), that he returned to Australia and arrived for the first time in Sydney in 2008.

A sense of place, one that is specifically antipodean in its sentiment, is something he considers integral to the ideas and sensibilities of his work, despite his remarkable Italian heritage. “Even when I’m photographing overseas,” he says, “my predominant thought is all about Australia, and how similar everything looks to Australia.” It’s a theory of universal likeness readily discerned in many of the works exhibiting now as part of New Documents: (all true things are equal) at Hotel Hotel’s Nishi Gallery in the nation’s capital. The exhibition’s title takes it cues from a 1967 MoMA exhibition, New Documents, which the artist describes as an unassuming show that featured the work of three artists whose highly personal works – an aberration from the formality and convention championed by their predecessors – went largely unnoticed at the time. The participating photographers were Diane Arbus, Lee Friedlander, and Garry Winogrand.

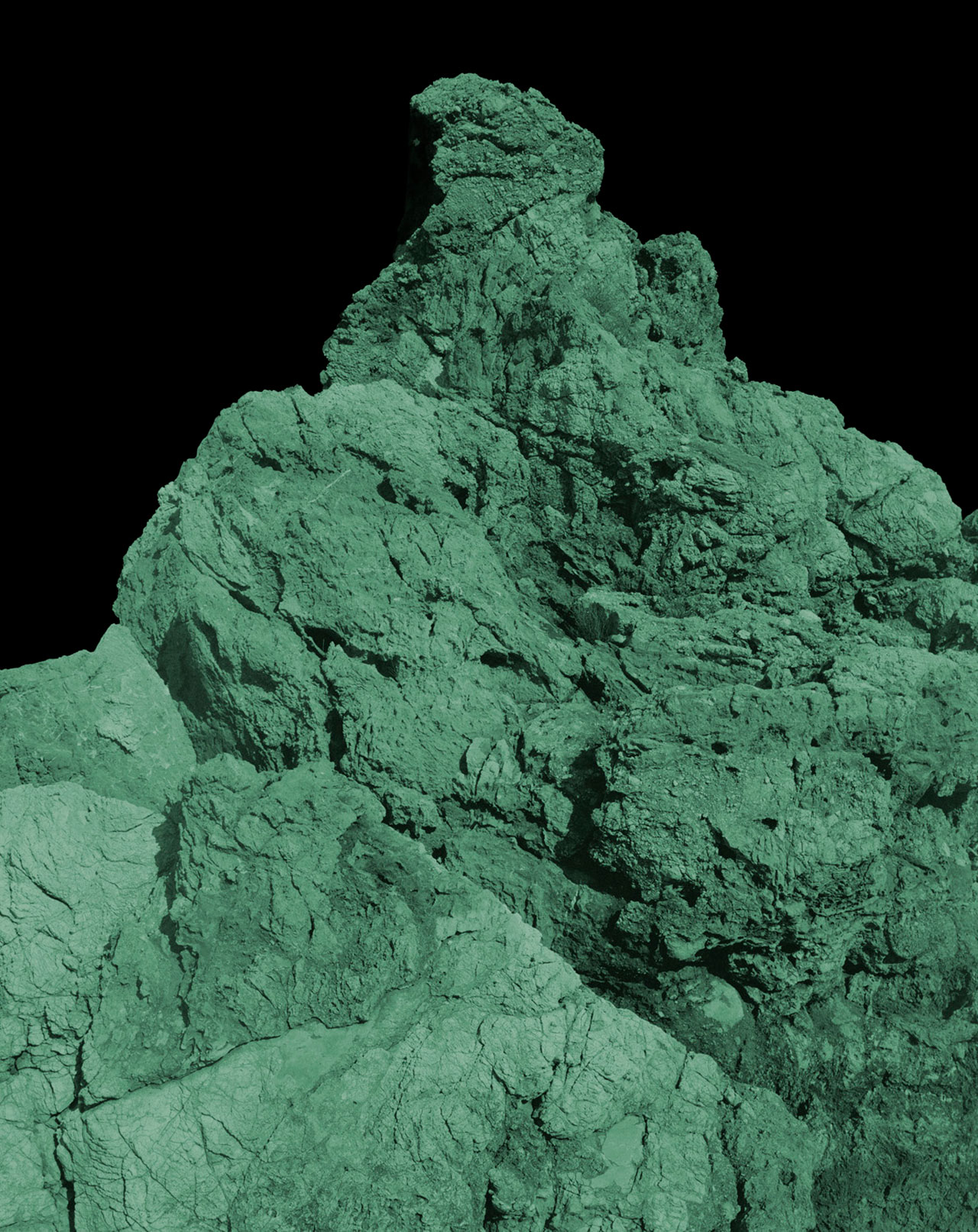

With New Documents, Celestino has charged himself with continuing the exploration of this ‘new’ tradition of photography by pushing what he describes as the techniques and aesthetics of both colour theory and landscape photography to “more personal ends”. The resulting survey pairs seemingly unrelated images together in formally and poetically charged sequences of abstract and natural occurrences – think striking landscapes Celestino has revisited repeatedly throughout the years with ostensibly arbitrary assemblages of objects. The act of juxtaposition not only draws out those associations in isolation, but seeks to document the manner in which we make those connections intuitively during short-lived moments of clarity brought about through an engagement with the natural world.

“There’s one picture [taken] in a field outside Bari in Italy, which is quite a rough city,” Celestino recalls. “I stood there, and I looked at the ground, [smelled] the air, the flowers and the sky and I could have been standing in Bungendore [a country town not far from Canberra] at sunset… We all have this capacity to appreciate the same things, no matter where we come from.”

“Identity is a really fickle thing. It’s all kind of a mask, isn’t it?” the artist ponders aloud, catching himself seconds short of slipping into a reverie, an internal odyssey of the kind that gazing on his work is prone to induce. He remarks that his chosen profession suits a lifelong preference for solitude; the precision of the medium itself is a conduit to time spent meditating (and grappling) with those kind of ‘big picture’ themes you might not ordinarily expect a photograph of turbulent whitewash to dredge up. Celestino shoots, though not exclusively, on either a large format analogue camera made by a dentist in Michigan, or on a 8×10 Explorer and an 8×10 Compact II lightweight camera both made for him by Dick Phillips, of R.H. Phillips & Sons (they are “the holy grail of large format cameras”). Process, rather than technology, is of utmost concern; repetition is not something to be wary of in his practice, rather embraced in much the same way that, for many people, the cyclical patterns of a yoga practice are seen to be enriching rather than enervating – or in the same way that waves breaking ceaselessly against a shoreline might prove to be a restorative or revelatory phenomena, rather than a maddening exercise in banality. Nothing happens quickly with these kinds of cameras, and in that sense, the format dictates the eventual photograph and imposes limits on the artist that otherwise would not exist. Without endless reels of film or the boundless ether of the Cloud at his disposal, Celestino is instead forced to perform the necessary mathematical calculations the camera requires of him before simply sitting and waiting for that decisive moment to arise.

“[You] just sit there and you wait,” he says. “And then you think about it, and then you think about it a little bit more. And then sometimes you miss it. And then you regret that you didn’t take it, so you end up taking one. And then you look at it later and say, ‘Ah, that’s amazing.'”

The sequences within New Documents draw on stories that Celestino’s father told him and how, when the photographer went to decipher those memories for himself, he found that he had created his own memories to sit alongside those of his father. It’s a call and response, he says, between images and across generations. That revelation accounts for the way that the show has been structured, with the images clustered into miniaturised narratives that invite closer inspection. The photographer’s hope is that, once an image works on its own, that the combination of two photographs will elicit “a third special thing [and] if you put a whole sequence together, hopefully it goes from being not only beautiful, but perhaps remarkable.”

Celestino’s parents emigrated from Calabria in Italy’s south, from “not a very pretty part right down in the toe” at a juncture between the first and developing worlds – the sort of place where “you’d be lucky to get power all the time.” Though they would eventually meet in Australia, both came from villages found not 20 kilometres apart. The son of an orphan and one of twelve children, Celestino’s father worked first as a shepherd then as a truck driver, all by the age of 12 – a situation the photographer never quite grasped the gravity of until having a child of his own, a daughter now aged five. One of the images included in New Documents is Celestino’s attempt at reckoning with the events that forced his father to leave Italy when a truck he was driving to Turin was hijacked. Rather than return empty-handed, and at the suggestion of his assailants, Celestino’s father boarded a boat and sailed first to Lebanon, before migrating to Australia through South Africa by water. That journey is the beginning of an endless spool of thread that the photographer says is woven throughout all the work he has made since.

To view Celestino’s work, you might think him a born and bred Sydney native. He is perhaps best known for a series of works collectively titled Surface Phenomena, a series of admittedly stunning seascapes that speak to a fascination not only with the ocean as it appears, but also with the amorphous idea of staking claim to the sea itself and attendant ideas about borders – specifically, just how arbitrary, and harmful, they can be in their capacity as fictional political devices. “Oceans can look like glass one day and be horrible the next,” says Celestino, who in 2001 salved the confusion, extreme frustration and anger he felt at the sinking of SIEV X and the loss of 350 lives, most of them women and children, with photography. “I wanted to just get out of my normal routine, so I started taking photos of the water, just as a meditation [and] just like catalogue, every day, just something to do,” he says of using his chosen medium as a means of self-care. “And that became the Surface Phenomena series.”

There’s a healthy dose of delight, scepticism and even incredulousness readily discerned in hearing Celestino describe the inherent subversion of the Surface Phenomena photographs, which were captured methodically atop an otherwise unremarkable set of cliffs in Bronte, day after day, year after year, before being exhibited at Olsen Irwin gallery in 2016. The photographs were then compiled into his debut monograph of the same name, which made its debut at the Tate Modern. “It’s a little bit like sneaking my message into people’s living rooms,” Celestino concedes of the unexpected subterfuge and deeply political undertow of his most popular works. “People are like, ‘Oh I love the ocean. I’d love to have one of these in my living room.’ And there I am, [saying], ‘Yeah but you know what it’s about, don’t you?” People don’t tend to look past the surface of things, the photographer contends – of the ocean, of a photograph or of the medium itself. It’s a sentiment that doubtlessly rings true of the city, and the country, in which the series was made.

“We’re this country that’s literally girt by sea,” he continues. “And the shoreline is the flashpoint for everything in our history as well. But we’re almost oblivious to it. When the western world landed on the shores here, that’s where everything happened. We don’t talk about the conflicts with the Aboriginals, really. When I went to school, you literally saw a boomerang, and they didn’t talk about anything else. They talk about Captain Cook. There was nothing about Aboriginal culture. It wasn’t till much later on that there was even some kind of acknowledgement about First Nations.”

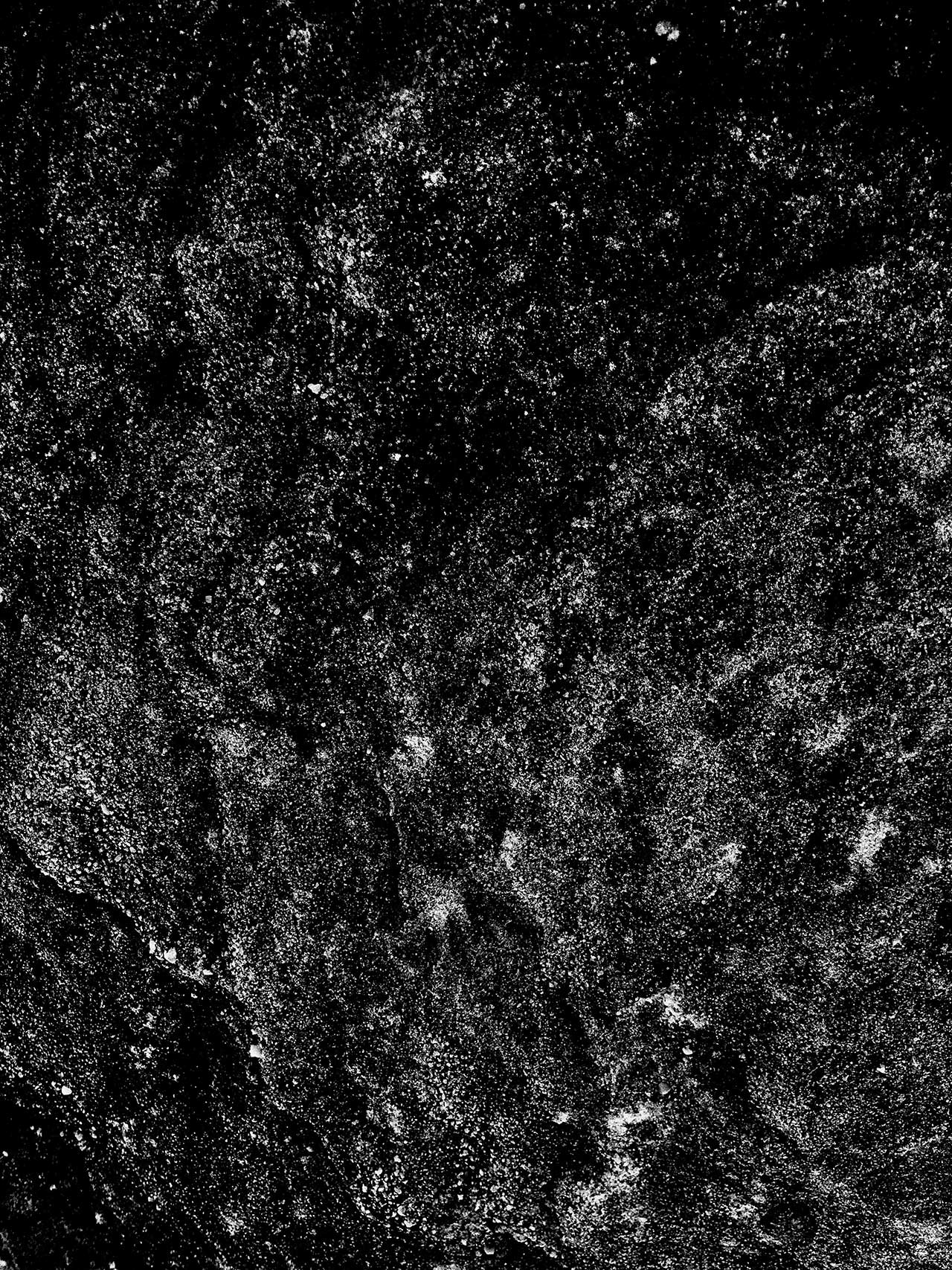

Over the years that he was working on Surface Phenomena, revisiting each day the same spot overlooking the ocean, Celestino began noticing unassuming details within the landscape that heretofore felt inconsequential. In particular, the elements had washed away the cliff face to reveal what “looked like teeth stuck in the rocks.” On one occasion, the artist, who says he is rather ironically nearsighted, removed his glasses and was struck by the feeling that those calcified sedimentary deposits in the rock around him were suddenly imbued with a vast importance beyond what he had initially thought. “You know when you stare at something in really bright sunlight and you turn away and there’s little stars in your eyes?” he asks. “It was [the same] of these little white rocks that look like teeth floating in the outer space. I had this weird connection where I was kind of like, ‘Oh yeah I can see it’. You know, we’re all connected. This is us. There’s no different between the sky and the nighttime sky and this rock, if you look closely enough. It’s the same pattern everywhere.”

He was moved to photograph the terrestrial constellations on his phone – another radical departure, he says, from “the rigid, brutal approach approach that I’ve had to landscape photography for so long. “I’ve always struggled with black and white photography [especially], because it’s so, kind of, ‘classical art photography’. We’ve been through that. And so, this is me coming around full circle and saying, ‘right, I’m here. I’m going to start again.'”

New Documents (all true things are equal) will exhibit until January 28 at Nishi Gallery by Hotel Hotel in Canberra. More information is available here.

Tile and cover image: Bartolomeo Celestino/Courtesy of the artist and Nishi Gallery