News feed

Recently, I sat next to a man on a plane who did absolutely nothing for the duration of the flight. I mean it – he didn’t watch a movie, didn’t thumb through a book, didn’t aimlessly scroll through photos of the trip he’d just been on. He stared straight ahead, silent and vaguely peaceful. To say that we were the classic odd couple of that flight is probably unfair to this man; I can see why he wouldn’t want to hitch his wagon to me – I’m very annoying on planes. I have a whole routine: pre-downloaded movies, three books jammed into the flap of the seat in front of me (because it’s important to have options), various snacks forming a perimeter around my seat, a range of hydrating balms and creams (and a 2-litre water bottle, which inevitably spends the flight rolling up and down the surrounding aisles) to ward off in-flight dehydration.

But in a sense, we were the classic odd couple – where he was placid, I was excitable, manic, busy; where he was tranquil, I was speed-eating m&ms like it was a competition. After I’d bumped him a few times – while adjusting my iPad to achieve an optimal movie-viewing angle, or pulling out one of many hand creams, or offering him some of my m&ms (he declined) – we started chatting. I had to ask him what he was doing: ‘Are you meditating? Reflecting on your trip? Are you thinking about what to watch? I know, it can be hard to decide.’ He replied good-naturedly: ‘No, just… relaxing.’

This made a huge impression on me, because it felt like such a rarity. I guess that’s not surprising, given the current cultural obsession with productivity. The idea that we can constantly work more and do more and be more has become the prevailing logic, beginning with our relationship to work. Erin Griffiths writes about the rise of ‘hustle culture’ in the world of work for the New York Times, observing (facetiously but with grim accuracy), ‘I saw the greatest minds of my generation log 18-hour days — and then boast about #hustle on Instagram. When did performative workaholism become a lifestyle?’

The drive to optimise every second of our time does not end with work. It’s seeped into our private lives as well, prompting a relentless audit of the way we spend our personal time – should I be waking up half an hour earlier to meditate? Should I get into yoga? Should I listen to a podcast while I’m on a run, so I learn something and get my cardio in at the same time? No shade to these activities, which all have ample mental health benefits (and if you have the attention span to listen to a podcast while running, power to you). What I find problematic is the constant pressure to do more with our time; to strive to achieve, relentlessly, even in our downtime. In a New Republic article, Nick Martin describes the way that hustle culture infiltrates every corner of our minds and lives, describing this mindset as, ‘the idea that every nanosecond of our lives must be commodified and pointed toward profit and self-improvement.’ This trend runs alongside the proliferation of social media, which turns private lives into performance and diffuses our attention among countless competing interests. It coincides with the way that boredom has become anathema to our society, causing André Spicer, a professor of organisational behaviour at City University of London, to write for the Guardian that, ‘in a world that values being interesting and busy, boredom can feel like a personal defect.’ And in a capitalist society, the culture of hyper-productivity can unsurprisingly manifest in the feeling that we should convert our personal time into something that reaps financial rewards. In a memorable article for Man Repeller, Molly Conway writes about the ‘modern trap of turning hobbies into hustles’: ‘we feel beholden to capitalise on the rare places where our skills and our joy intersect, we underline the idea that financial gain is the ultimate pursuit.’

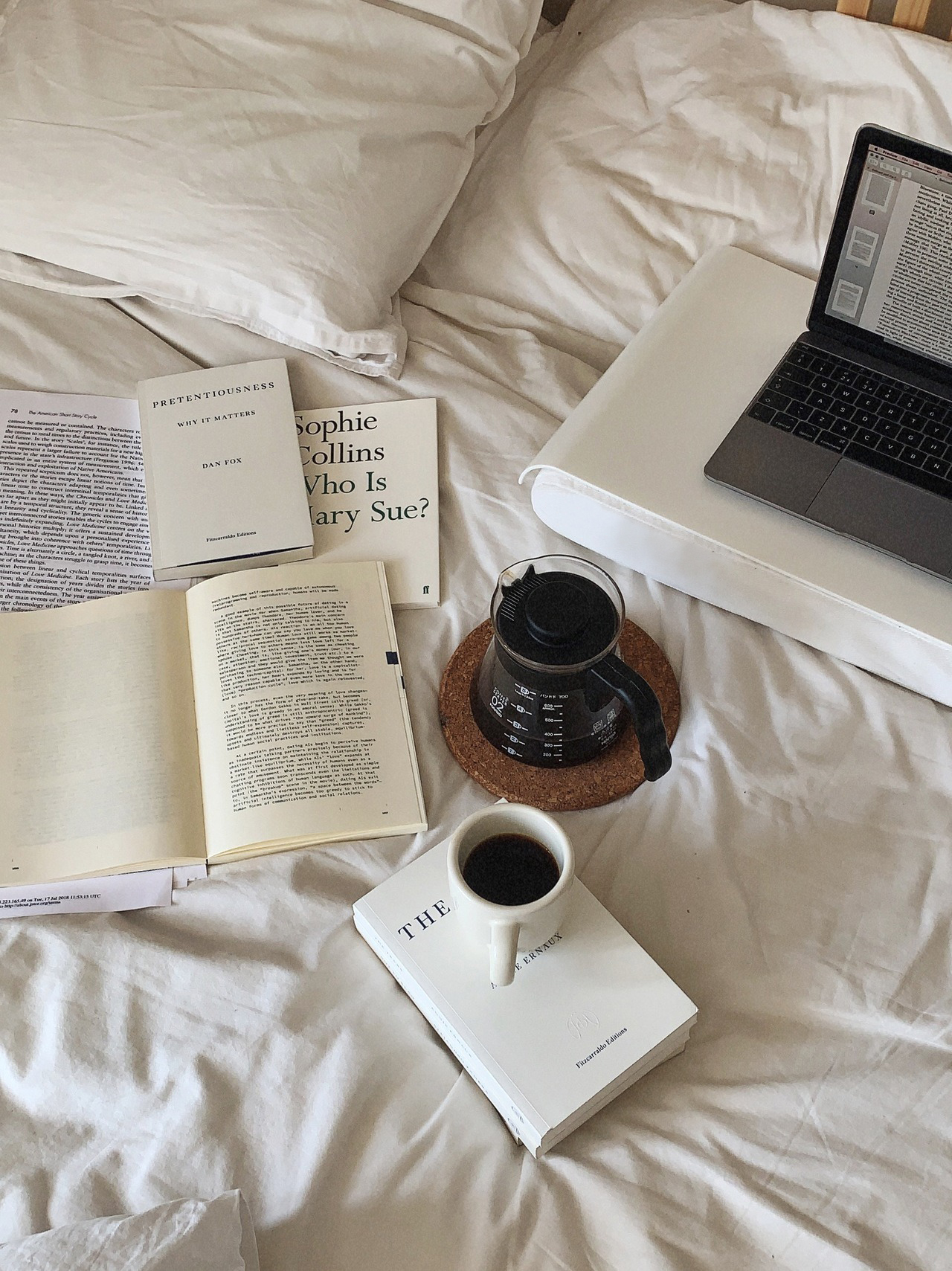

I’ve been thinking about this a lot lately, as the content reminding everyone that Shakespeare wrote King Lear and Isaac Newton invented calculus during past plague-related quarantines, has done the rounds. And then there’s the parade of social media images, showing breads baking and home workouts executed and creative projects simmering along. With the majority of us confined to our homes, with ample time to get lost in the fuzzy haze of the scroll, these images are seemingly everywhere. In one sense, this is lovely – it’s wonderful that so many people have found productive or meditative outlets in a completely stressful time. But there’s a dark side, too – feeling guilty that we’re not doing enough relative to everyone else, or not meeting the bizarrely ambitious benchmarks we’ve set for ourselves. On her podcast, How to Fail, Elizabeth Day talks about, ‘the weird daily guilt that you haven’t got down to writing that life-defining novel that now you’ve got time to write, or [that] you’re not home schooling your children sufficiently.’ This guilt is the ugly other half of our tendency towards the super-humanly productive. When that’s our normal, it becomes tempting, even in these extremely abnormal circumstances, to maintain momentum (or even to ramp it up, now that we have all this additional time).

Chris Bailey, a productivity consultant, is quoted in the New York Times about this tendency: ‘It’s tough enough to be productive in the best of times let alone when we’re in a global crisis… The idea that we have so much time available during the day now is fantastic, but these days it’s the opposite of a luxury. We’re home because we have to be home, and we have much less attention because we’re living through so much.’ Of course, this does not apply to everyone – to frontline workers, who don’t get the luxury of choice when it comes to being productive right now; or the many who have lost jobs, for whom staying busy might feel like a comfort. But for many of us, it’s a useful reminder: with everything that’s going on, it’s natural to feel fatigued and anxious. To lack mental space for much more than fulfilling basic needs. A friend told me over the weekend that she feels like she should be watching all of the new shows everyone is talking about; but right now, all she can handle is the sweet, sedate, comfort blanket of Gilmore Girls re-runs.

Given our usual obsession with productivity, slowing down or doing nothing might feel unnatural. But now, more than ever, it’s what we need. This means changing our mindset about how we spend our time – focusing less on achievement and doing, and more on putting one foot in front of the other, and taking care of ourselves and others. It means leaning into boredom, rather than trying to escape it (not only are occasional bouts of boredom a perfectly fine alternative to constantly striving to maximise our productivity – they are actually more valuable than we realise, with studies finding that ‘we may be at our most creative when we are bored’). So let’s spend more time staring into space, without wondering where that will lead us. Let’s do things for their own sake. Let’s remember that these are bizarre times, and it’s okay to just take a minute.