News feed

By any measurable metric, few in his field have enjoyed the successes that Jon Kortajarena has in his 15 years of modelling. To his name – that’s Korta-ha-ren-nah, delivered with all the acrobatic finesse of the Spaniard’s mother tongue – countless conceivable accolades have been affixed. The more hyperbolic, the better: accolades made all the more impressive for their singular inversion of the modelling industry’s gender norms. Most iconic. Sexiest. Most stylish. Record-breaking. Highest paid. It would be all too easy to dismiss each as the confluence of goodwill, great genetics and even better luck. On the latter, Kortajarena would agree: luck has played a starring role in his life, a supporting turn deserving accolades of its own.

“I was lucky and everything came when it [had] to come,” Kortajarena told GRAZIA between slices of margherita pizza and dizzying amounts of Diet Coke – consumed on set with no discernible side effects. “And [it happened] the way it was meant to.”

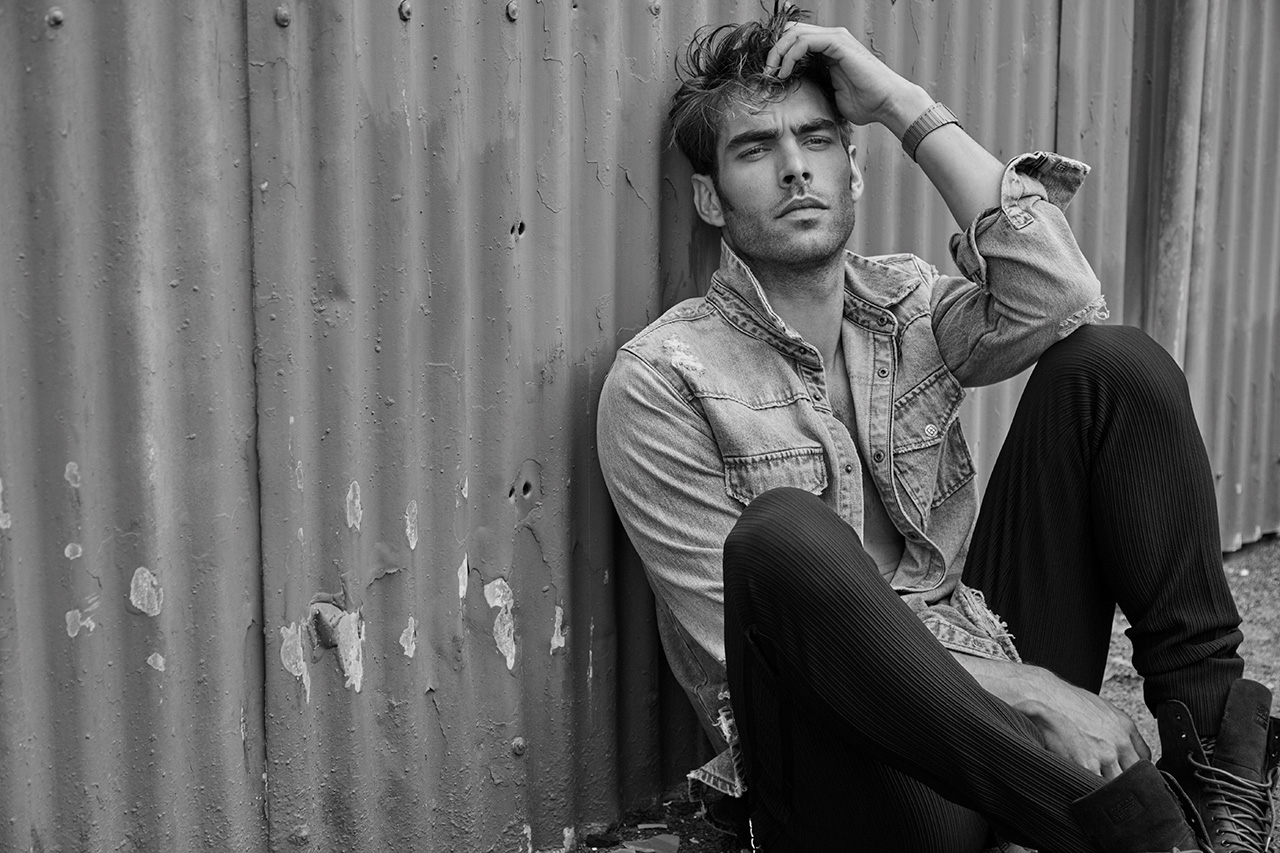

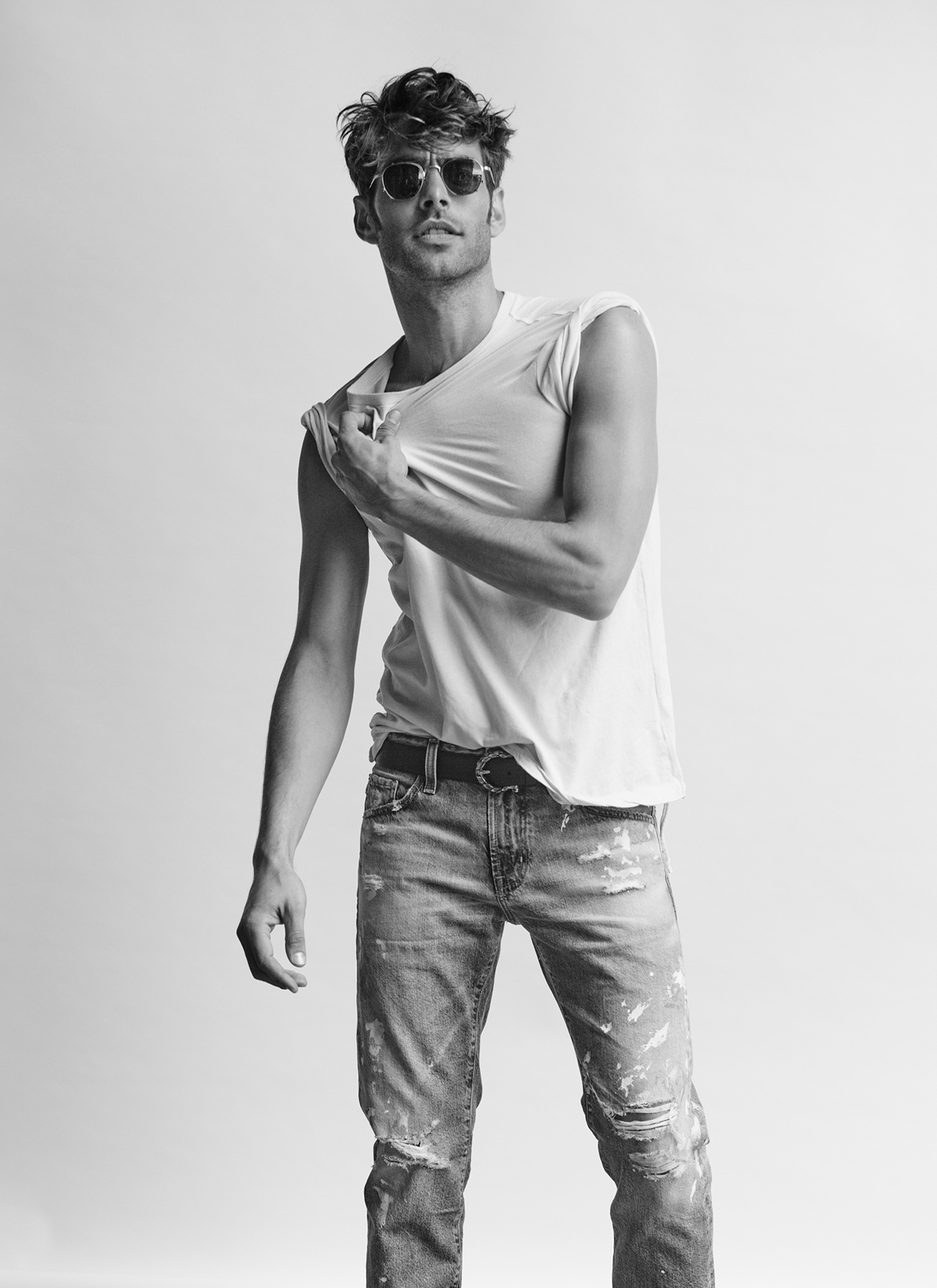

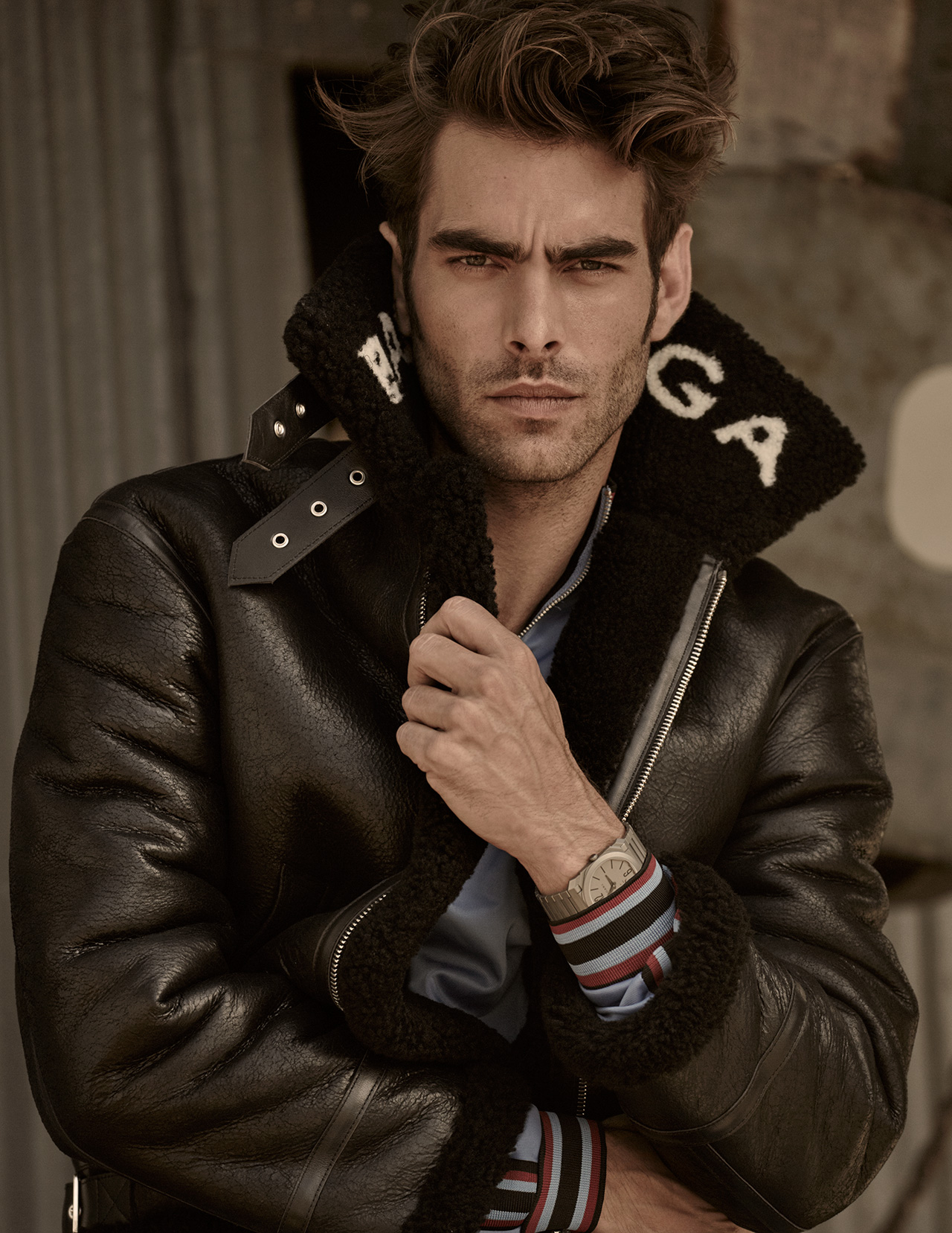

It’s only once you witness Kortajarena at work that evidence of a craft which can’t be fluked or brought on by chance alone becomes clear. “I have [to have] an action, otherwise I feel like I’m posing too much,” he says. So he perches atop a bollard, absent-mindedly retying his shoelaces while his eyes barrel ahead directly into the wind in a defiant smoulder. The pose, however, isn’t quite working. An assistant fetches a piece of driftwood, placing it beneath the model’s boot to bring his knees to a more natural resting position that’s uncanny in its resemblance to Rodin’s pensive Thinker – only sharper and more precise than the statue could ever hope to be. He thrusts his left arm forward like he’s drawing a weapon in a stand-off against the photographer, the movement pulling back the cuff of his sweater to reveal an all-important Bulgari watch. This, evidently, is not his first rodeo.

Later in the day during a portrait session, Kortajarena wheels out a succession of almost imperceptible and vaguely mathematical movements while adjusting a neckerchief. Captured in rapid-fire succession, each of the infinitesimal shifts registers only long enough for the shuttering of the lens before body and mind alike have moved on. Really though, little more than a minute tilt of the head is required when the algorithm works as well as this one. Every few frames, Kortajarena stops to touch his hair – a tic he confesses to before the first frame of the day. An assistant approaches to show Kortajarena a reference for the final shot.

“I can be anyone you want me to be” is all he offers in return.

“Pretending to be the perfect man”, however, well that’s a “pain in the ass”. Kortajarena laments a recent drop in sophistication in his industry – a sense of integrity that has lost out to the relentless pursuit of more followers, more eyeballs with shorter attention spans. Before, he says, there was beauty, transgression and a message. Now, artifice has overturned artistry and “everything is becoming a show. The mask.” That’s why, above all else, the model started acting: to celebrate his fears and vulnerabilities, to stop the kind of posturing and pretending on which he has made his name, and to shed whatever guilt or doubt he may be feeling at any given moment. “Pretending to be perfect, first, is exhausting,” he says. “And second it’s surreal because nobody’s perfect. Nobody.

“Everybody’s made of lights and shadows. And you cannot hide the shadows because they are part of you. So, when you are really young, you don’t even see this that much. When you spend enough time in the industry, you start seeing that part. At some point, it’s a necessity to take care of that part too. When I work as an actor, I can also take care of that: being honest, and not ashamed.”

It’s difficult, though not entirely inconceivable, to imagine that Kortajarena was an extremely shy child, and later, a shy teenager coming of age in Bilbao. The city, an industrial port town in Spain’s northern Basque region, is bisected by the river Nervión, the mouth of which unspools with a Spanish sense of urgency into the Bay of Biscay. Bilbao town-proper lays further inland from the sea, the contours of the city shaped as much by the river’s agreeable ebb and flow as by the mountains that part like lips on either side. In the middle of town is Frank Gehry’s Guggenheim, a glittering titanium veneer that, like the brackish estuary and its cargo, ferries life in and out of the city. It’s not surprising then that as a child Kortajarena dreamed of seeing the world beyond the city, its river and its hills. He just didn’t know how he was going to get there.

Another tic: Kortajarena frequently and unwittingly slips into the kind of bright-eyed reveries that are an occupational hazard for those with the kind of bone structure that could moonlight as a meat cleaver. “I’ve always been a dreamer, and I try to keep that,” he says, slipping into one of these winsome whirlpools that follow the same pattern as the stubble on his face, tightening and whorling until it disappears precisely on the angle of his jutting mandible. “Even if sometimes life is difficult, you still have to keep believing in life and humanity, no?” It’s impossible not to get sucked in too.

As a child, Kortajarena told his mother he wanted to be an actor. The financial and logistical challenges of relocating to Madrid, the cosmopolitan metropolis south of Bilbao, prohibited him from doing so but the dream lay dormant until he could finally enrol in classes. “It wasn’t the moment I was expecting to do it, but when something is meant to be, it’s meant to be.”

Even if you do not think you know his face – perhaps you suffer from prosopagnosia, facial blindness, a condition for which Kortajarena is likely the untapped cure – you will almost certainly have seen it almost everywhere. Perhaps you saw the exquisite A Single Man, the directorial debut of multi-hyphenate aesthete and designer-turned-director Tom Ford. The film provided Kortajarena with his acting debut; he played a hustler, Carlos, whose momentary encounter with the titular single man, played by Colin Firth, proves to be so intoxicating that life and lust brilliantly and briefly flood back into the protagonist’s world. “You have an incredible face,” Firth’s moribund George tells Carlos in perfect Spanish. “Enjoy that. It’s a great gift.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5MCgJOxw788

Greater still is the gift that Ford has given Kortajarena in return. The two first met in 2007 when Ford, former creative director of Gucci and Yves Saint Laurent, was launching his eponymous label, founded on a menswear offering that had its premiere outing live on The Martha Stewart Show. Against the frippery and abundant fernery of Stewart’s set, a timid Kortajarena, then 22, parades the first of four evening looks in a procession that seems provincial in retrospect. He wears an eight-buttoned double-breasted cashmere suit over a cashmere turtleneck with crocodile tasseled loafers and thick-rimmed black spectacles. His hair is slick, parted to the right with military precision and framing his face like a lopsided comma.

“You look elegant, and comfortable and warm. It’s a fabulous look,” Stewart, who has built an empire on detail-oriented fastidiousness, tells Kortajarena. “Do you wear glasses normally?” But it’s too late for a follow-up – the model has already begun to walk off set, oblivious to the question left lingering by the queen of daytime domestic television. Undeterred by the blunder, Ford went on to book the young model for a campaign, the first of many over the past decade. Theirs is a particularly fruitful relationship that Kortajarena never could have imagined would progress so far, and one from which he has learnt a great deal – not just the variations and intricacies of “fabrics, cuts, how to wear a pocket square [and] how to wear cuff links”, but also how to carry oneself in the world.

“How kind [Ford] is with other people, that’s also a reference for a man,” says Kortajarena. “When you are growing up, you have the values your family taught you. But when you grow up, you see men in the world [and] they become a reference. Colin Firth was one of them when I worked with him. Tom Ford [is another]. When you admire people, you try to take things from them, and they make you a better person.”

In a case of art imitating life Kortajarena has his hair cut by his mother, like his character in A Single Man. She’s the only person to whom he’ll turn when the time comes for a trim, often rerouting a flight from Milan to his home in London through Bilbao. Not just because theirs is a bond he prizes above all others, but because “she’s an amazing professional”, he says. In the modelling world, your hair is as good as your currency, and Kortajarena understands all too well the life-changing consequences of a chop. “As a model, if you don’t have a good haircut everybody tries to fix it. And you’re fucked.”

Aged 19, Kortajarena quit modelling. He had had an enviable start, landing campaigns for Just Cavalli and Versace soon after he was discovered in Barcelona at, of all places, a fashion show. In the latter campaign, shot in New York by Steven Meisel, Kortajarena’s exuberant Rococo silk shirt pales in comparison to a shock of shoulder-length chocolate brown hair made bouffant by wind machines. Granted, it’s the endearing vulgarity of the get-up that first catches your eye, but it’s the shank-sharp contours of his face, that transcendent smoulder and his lustrous hair that retain your gaze. Things were off to a great start. Then, suddenly, the work stopped.

At the time, Kortajarena assessed the risks. He would only stay if the work, the travel and the connections made it worthwhile. But if he could make the same money doing something else, why risk wasting the best years of his life at the whim of a fickle industry? After all, his mother, who had expressed concerns when he first embarked on a career, had already given birth to her son at the same age. He cut off all his hair until there was little of its former glory left – “Cutting the hair was a big decision,” he reflects – and returned to Spain. That’s when, he says, everything suddenly started up again.

Since his 2009 debut in A Single Man, Kortajarena’s overwhelming ambition has been to act, all the while never relinquishing his blue chip campaign credentials. He recently scored a recurring role in the American legal drama Quantico opposite Priyanka Chopra, and wrapped filming in Venice, Italy, on The Aspern Papers with Vanessa Redgrave and Jonathan Rhys Meyers last year. Both roles required that he empty himself of any ego and prejudice to fully inhabit his characters; his Quantico role, for example, espoused an Islamophobic world view entirely removed from his own. It’s the deeply psychological work of creating a character’s interior architecture that he relishes most. Of course the costumes help a lot, too. Later this year, Kortajarena will headline the cast of La Verdad (Truth), a Spanish television series that tested both his leading man credentials and his belief in his own acting abilities. The crime drama has given him a level of trust in his work that had eluded him in prior supporting roles, say the ‘Milfman’ in Fergie’s M.I.L.F. $ music video.

Perhaps most transformative of all his roles was the experience playing Guille in Spanish filmmaker Eduardo Casanova’s surreal rose-hued debut, Pieles (Skins), which has been likened as much to the work of Pedro Almodóvar as John Waters. Kortajarena played one of eight unfortunately malformed characters afflicted with deformities ranging from the extreme yet believable (Kortajarena’s character suffered severe burns to his entire body inflicted by his mother when he was a child, thus growing up scarred in every imaginable sense) to the transgressive and utterly bizarre (perhaps most famously, one character’s digestive system had been, to put it politely, inverted on both ends).

“When they finally put me [in] the mask, and the makeup, and the [prosthetics], suddenly, I saw myself in the mirror, and I was scared of myself, but at the same time, I could recognise myself in the eyes,” says Kortajarena, recalling the experience of seeing his character fully realised after months of internal preparation. “Suddenly all these questions came to my head – questions that [had] already [been] answered a long time ago. Well, when you have your face burned, all those questions have to be [asked] again, and they have very different answers. “And, silently, I was looking at myself and thinking, ‘Am I still valuable? Am I still a beautiful person? Am I still someone who’s worth it?’ Because with this face, nobody’s going to accept me. And suddenly, you start this mental process of how it must [feel] growing up with no [acceptance], growing up feeling that you’re [not] worth it [and] nobody can look at you because the mask is not valuable for them. [Guille] is like, ‘Well, I have much more to give and much more to offer, and I have things inside that make me really valuable.’”

There’s a line Kortajarena’s character in A Single Man offers Colin Firth by way of a small parting consolation that bears repeating here: “Sometimes awful things have their own kind of beauty.” As he has aged, Kortajarena – soon to be 33 – has come to understand karma’s role in his continued success. Nothing has come for free in both his professional and private lives, despite appearances that suggest otherwise, and every success is now tempered by the knowledge that at any given moment the ride – he likens it to a roller-coaster – will inevitably come down. “You have to be decent,” he says, “It’s karma. It’s like your behaviour affects your circumstances.”

Kortajarena is an ambassador for both Save The Children and Greenpeace and recently travelled to Vanuatu to meet the world’s first climate change refugees; their lives have been entirely displaced by the brutal effects of the changing environment. Despite the dire nature of the crisis, the trip was a beautiful experience, something entirely transformative and, when removed from the stultifying banality of the news cycle, utterly affecting in ways Kortajarena could never have anticipated. He is plainly aware of the cliché – model-slash-actor visits disaster zone – but it’s when he relays this story, or tells another of his visit to Nepal after the 2015 earthquake, that he is at once stricken with speechlessness and unable to describe the enormity of the experience fast enough. His passion is readily discerned here on a level comparable to – if not greater than – when he talks about his lifelong love of acting. This is the real deal, he seems to be saying. Everything else that has happened until now has just been playing pretend.

On the nape of Kortjarena’s neck is a tattoo. It looks like a crude rendering of barbed wire, but it is, in fact, a tree. From two roots spring forth two branches surrounded by a halo of greenery in silhouette. It’s a Kortajarena original, albeit one drawn when he was five and revisited much later in life before made permanent. Kortajarena has spent the last seven years building Casa Sua, a boutique hotel villa located in the northern village of Famara on Lanzarote, one of the Spanish Canary Islands off the northwestern coast of Africa. The incredible natural beauty of the place, its volcanic black sand and sunsets, have captured his heart. He first visited as a child with his mother and younger sister, only to return years later with friends and fall in love all over again. The opportunity he has today to share the house with those friends, his ailing grandparents, his cousins or tenants alike is his biggest pleasure. Never does he feel closer to the earth than when he is there. During the day, the light changes the colour of the volcanoes that gild the horizon from brown to red to green, but it’s at night, once the sun has scrubbed the earth of its pigment, that Kortajarena feels most at peace, and most like himself – finally unmasked.

“I needed a place to escape,” he says. “I wanted to be in a desert with amazing nature; a place where nobody give a fuck if you are Beyoncé or a carpenter. Nobody cares; they just respect you for who you are. Nature is huge in Lanzarote. Just enjoying that makes you feel grounded.

“It makes you realise that you are nothing.”

Revisit GRAZIA’s Identity Issue cover shoot with Jon Kortajarena, shot by Simon Upton, in full here.

Tile and cover image: Simon Upton