News feed

The cold sinks to the bottom of the valley hemming part of the Phinda Private Game Reserve. We burst at speed through bracing pockets of cool air as our three-tiered Jeep hurtles towards the other side of a ridge, the clear dawn breaking beyond. Were adrenalin not already doing the trick, there’d be no more enlivening way to begin the morning’s mission. A martial eagle — the largest of its kind – circles above like a cloud fallen from the basement of heaven. Hordes of lappet-faced vulture watch on from the branches of thorned acacia trees. Twenty-five per cent of Africa’s 2000 bird species are found here alone, but we’re not here today to bird watch.

Overheard, a helicopter begins to circle, signalling that its target, a female white rhinoceros, has all but given up the chase through the waist-deep grass. She moves in a panic, zig-zagging through the undergrowth, and it soon becomes apparent she’s not alone. A calf, no more than two years old, is never more than a step behind. Its movement, flighty and afraid, is almost a precise mirroring of its mother. A high-powered explosive dart is fired from the chopper, and on impact, a vial of M99 — or etorphine, an opioid 10,000 times more potent than morphine and fatal to human touch — is released into her hide. Or, at least, it should have been.

A game-capture operation is an unusual set of circumstances in which to test the capabilities of a new smartphone, but my vision vacillates between the Leica-lensed Huawei P20 Pro in my hands, and the spectacle playing out before me, strangely unable to decide which version most closely resembles reality. Though the experienced team, including wildlife monitors, chopper pilot, several volunteers, and the veterinarian have ample equipment, there remains a margin for error when anaesthetising a two-tonne animal running at full tilt. Factor in a calf, and the matter is complicated slightly.

The land around Johannesburg is pond flat, yielding only to the sprawling, soupy city. As you make your way east toward Phinda, in the coastal South African province of KwaZulu-Natal, it dissolves into ploughed parallel lines broken by vast crop circles. Gradually, craggy ridges begin jut out of the earth like an overbite. The trees, once sparse or in lines along freeways, blanket the land like spores. Roads turn to dust, connecting a constellation of bush settlements. The earth, where visible, is blushing.

Phinda’s airstrip is guarded by electrical fences to ward off tampering elephants. Dormant aircraft’s wheels are caged to stop rabid hyenas. Impalas sashay along the runway. Warthogs bob along through tall grasses. Within a minute, we pull up alongside a herd of six zebra. A lone male stands to the side, flaring his nostrils and quaffing the air, which smells of damp earth and pheromones. Andrew, our ranger, asks that we stay seated at all times. Lions and elephants do tend to come quite close to the vehicle, he says, and this can be a matter of life and death. Lions hunt at night, however, and for now the sun is acting like the middle child born to overzealous stage parents, showing off in an “everything the light touches is our kingdom” kind of way, parting clouds and all.

Phinda is part of an ancient savanna ecosystem, its combo of impenetrable woodland and vast grassland the result of intense rainfall followed by arid winters. The Indian Ocean is 40 kilometres away, with its warm ocean currents and temperate air partly responsible for the area’s biodiversity. From atop a mountain range in the reserve you can see the iSimangaliso Wetland Park, one of South Africa’s first World Heritage sites, where the world’s tallest vegetative dunes rise up from the sea. Even when the wind drops, the grass here sizzles. We round another corner and there stand three white rhino: a mother, her calf and a male whose job description is something between perimeter monitor and perpetual nuisance. Rhinos are largely blind and rely instead on their exceptional hearing to gauge their surroundings. White rhino are more placid than their smaller black compatriots, who are about one tonne lighter and bear a grudge against the world for their perceived shortcomings. And confusingly, both are the same colour: neither black nor white, but an earthen grey, preferably slathered with cooling mud.

It’s hard to pinpoint a single reason why, but the threat to both black and white rhino intensified in about 2007. Some suspect an economic boom, particularly in Asia, contributed to the rising demand for their horn. Rhino at this time were being lost at the rate of 400 to 500 per year, though figures differ between reports. By 2012, that number had quadrupled; by 2014, poaching increased by 9000 per cent. The white rhino population is now estimated to be 20,000. For the black rhino, however, the situation is dire – only about 5000 remain. As far as defence mechanisms against predators fare, their two horns are dwarfed by their sheer size and heft. The horn’s value, then, is entirely perceived. It has no medicinal value, yet is prized for its supposed remedial properties for the flu, hangovers, or as an aphrodisiac. Prices vary depending on the animal and its “freshness”, but per kilogram (the average horn can weigh up to four kilograms), it can garner US$50,000 to US$70,000 on the black market. The horn often ends up in a powdered form, where it can fetch up to eight or nine million rand per kilogram (AU$750,000). Perhaps most upsetting is that the horn is made of keratin – the stuff of fingernails – and is capable of regrowth when removed correctly.

Conservation authorities were initially ill-prepared to deal with the onslaught of poachers intent on decimating the rhino populations. “We didn’t have inroads into the criminal syndicates,” says Dale Wepner, an assistant manager for the &Beyond Phinda Private Game Reserve. “We weren’t equipped and our field rangers were not trained to fight poachers; that wasn’t their job [to] counteract a full-scale war on rhino poaching. It took a number of years before the initiatives started to take effect as to how we were going to deal with this problem.” After a decade of persistent effort, research and substantially more resources, Wepner says a poaching is on the decrease, although losses sadly still occur. Wepner estimates more than two hundred rhino have been lost this year in South Africa. Losses are less frequent on private reserves — their relatively small scale means it’s harder to enter undetected. And although Phinda’s population is large enough to serve as an effective breeding unit, this also means it’s also large enough to land on poachers’ radars. Once significant losses were sustained, conservation authorities embarked upon what’s described by Wepner as “one of the most intensive dehorning programs in the private sector ever”. The process is extremely intensive and expensive, but for Phinda it has been the most effective tool against poaching, says Wepner, who concedes that while unnerving at first to see the animal without its horn, it soon became the new normal. A horn, now, is something of a red flag.

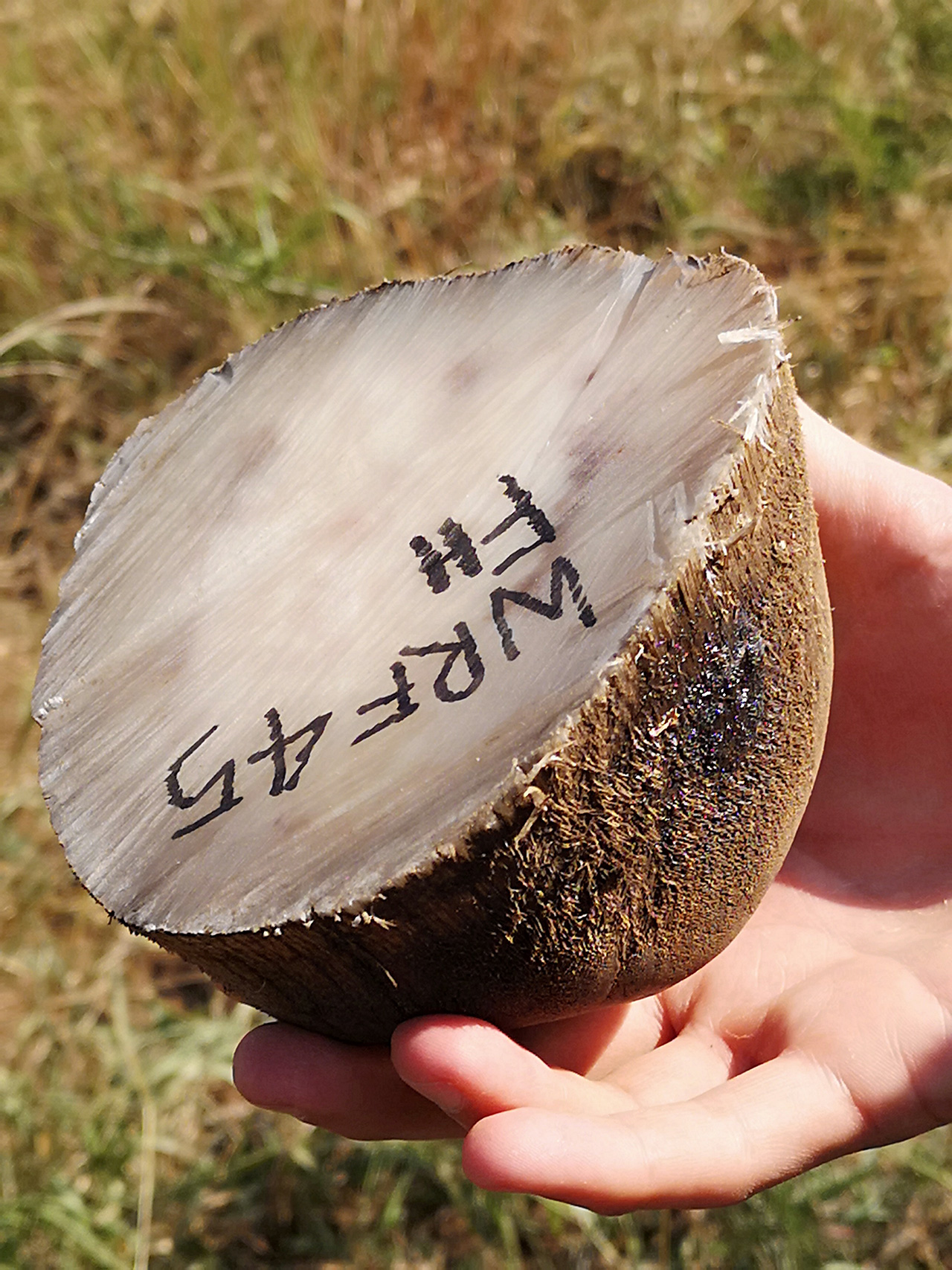

Dehorning is a continual process. Any regrowth is enough of a threat that regular maintenance is required. Once the animal is immobilised, the team — a pilot, a dozen volunteers, and the veterinarian, Doctor Mike Toft — conducts a full DNA sampling as per legal requirements, the results stored in a national database. Skin, blood, horn, hair samples are collected in vials. The rhino is microchipped, like you would a domestic animal. This is no ordinary beast, though.

A second dart is required to bring down the female white rhino we have tracked into open grasslands after the first failed attempt. Even at 100 yards, her distress at the prospect of being separated from her calf is palpable, their tandem dance heartbreaking. Many minutes pass, and slowly but surely she takes a seat. Her calf retreats to a safe distance and observes from afar. A teal blindfold is applied, as are earplugs. A jerry can of water is poured over her back, and the team assembles around her bulbous form. She’s warm to the touch, her flank a patchwork of armorial skin like parched earth. While the animal is kept half-awake to reduce the risk of respiratory stress, a second tranquiliser is administered to level her blood pressure; an enzyme then quickens its effects to reduce body temperature; and another narcotic is injected into her ear to relax the muscles and prevent their breakdown through stress, heat and exertion. Then the chainsaw revs into ignition. There are no nerve endings until just above the facial plate, but that does little to assuage the phantom pangs that erupt as the saw cuts into the horn and a noxious smell fills the air, like burnt hair. Splinters are sent flying, and only once you are covered in them — and hold the smooth, dead weight of the horn in your hands — does its benign nature become achingly apparent. It’s keratin. Nothing more, nothing less.

After 45 minutes, the tranquiliser waning, a reversal drug is administered and the animal awakes. Unsteady on her feet at first, the mother, safer now thanks to her involuntary rhinoplasty, takes a first tentative step toward the kind of reunion that can never be erased. We raise our smartphones in customary salute.

Elsewhere on the reserve, life goes on. A cheetah — stately and preening — slinks sylph-like through the reeds. She’s tracking a pack of impala, but is spotted by a bird, triggering a whisper network of kin who sound an alarm signalling her presence. It’s the bush equivalent of a group chat. Nearby, a young lion, the head of two packs who reside in Phinda, lies with limbs aloft in complete indifference to our presence. He is simply airing his undercarriage, only once raising his head and tossing his mane as if to say, “What, you’ve never done the same?”. Later, a sorority of lionesses will finesse every last scrap from the entrails of a lone nyala with bone-crunching clarity. The nyala are chalked with a white stripe along their spine that repeats in equidistant increments. “Cut here”, seems to be the inference.

Days go by, and all but one of The Big Five eludes us. We take a scenic detour to the airstrip for our departure, hoping to see one of the 111 elephants that reside in Phinda. We see trees felled, uprooted and eaten, their branches stripped of sour fruit. There are the telltale lines in the sand where these ‘Grey Ghosts’ have picked up the earth with their trunks and tossed it across their backs. Lumbering tracks imprinted into the dust. Heaving mounds of dung par-baked from the heat of the day. And then suddenly there they are, as if by design: three generations of elephants, standing serendipitously on Elephant Road. As they cross the track in single file and descend into the valley, we come to a standstill, awestruck, as the last of the Zuka herd wanders out of sight. Unbeknownst to us, an adolescent bull emanating a furious musk begins to charge at the vehicle and our guide, ever in control, hightails it to the airstrip as we’re chased out of the reserve by an elephant experiencing peak sexual frustration – the air no longer cold or dank but suddenly thick with furious pheromones, the sun beats down with renewed strength, and suddenly I’m blinded by the light and colour and shape of everything, and the thundering, heart-exploding wonder of it all.

Tile and cover image: F.R. Lawrence Lew, O.P.