News feed

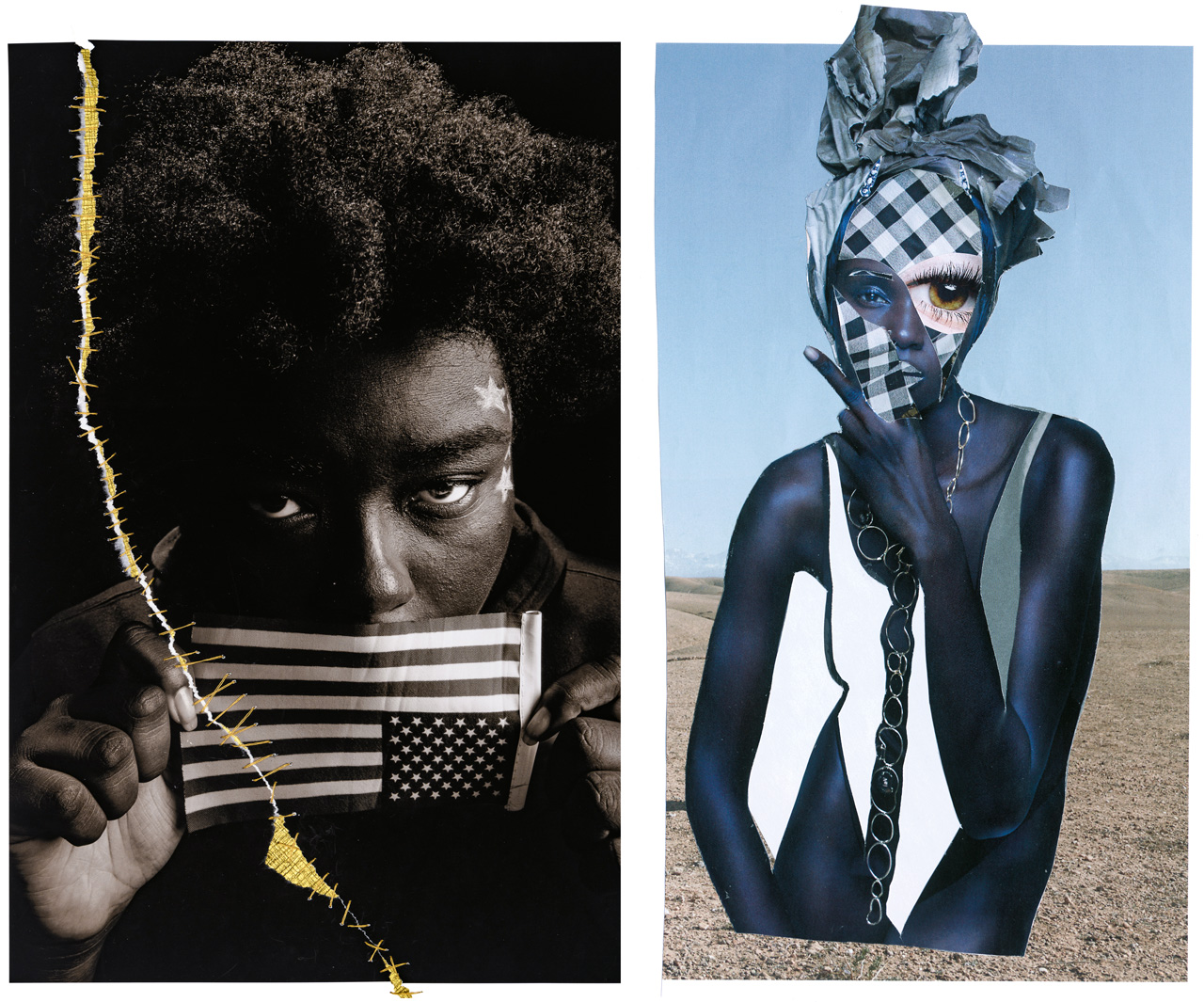

Can you remember the last time a piece of artwork really moved you? For the newest cultural series, “New Ways Of Seeing” GRAZIA will introduce a new artist each week who aims to change the status quo from gender rights, police brutality and social justice.

The global pandemic has led us on an exhaustive dance. We have found ourselves toing and froing, pulled apart by opposing and contradictory forces. The art world has largely been a victim of this undulation; finding itself stifled by lockdown policies and drained of funding channelled to frontline causes deemed more deserving. And yet, whilst we do not need art to survive in a physical sense, we need it now, more than ever, to help us to better understand the changing world we find ourselves in.

READ MORE: EXPLORE THE ‘NEW WAYS OF SEEING’ SERIES HERE

The enforced inertia brought on by museum and gallery closures has been met by new, increasingly digital, ways of reaching audiences and a focus on adapting to changed circumstances. For some artists, the extraordinary stillness and time afforded by global lockdown has resulted in prolific production; homes transformed into studio spaces, and a reimagining of traditional concepts of exhibiting work. For others, it has encouraged a more philosophical re-examining of their practice and a greater consideration of what their art is, or should be, or of what it might be capable of.

The pandemic has raised questions around education, social disparity, and sustainability, and has dismantled and disrupted key tenets of our lives that once seemed immutable. At the same time, movements like Black Lives Matter have galvanised a global conversation around systemic racism and forced us to confront uncomfortable, and very real, truths. There has been reluctance and disenchantment but there has also been immediacy – a frank, gloves-off take on social ills and a determined approach to righting them. If this period has taught us anything, it is that contemplation must be a precursor to change.

Art has a seismic role to play. As passivity moves towards action, many artists are using this opportunity to create art that is angry, dissenting, or a vessel for social critique, and producing works that highlight, and seek to overcome, failings in the system. The shield once provided by the concept of unconscious bias has been removed and artists are increasingly making their voices heard. For American artist Adrian Brandon, whose Stolen series of paintings hauntingly explore Black lives cut short by police brutality, art has “a tremendous role within activism because it engages people experientially through a visual language. It transcends language barriers, politics and party lines, and gives us a more universal reach. Art demands that we be vulnerable and engage at a human level, which is so vital as we work towards a just and loving world. The challenges of our times can’t be solved by politicians and policy makers alone. We need to engage both hearts and minds if we want real and lasting change.”

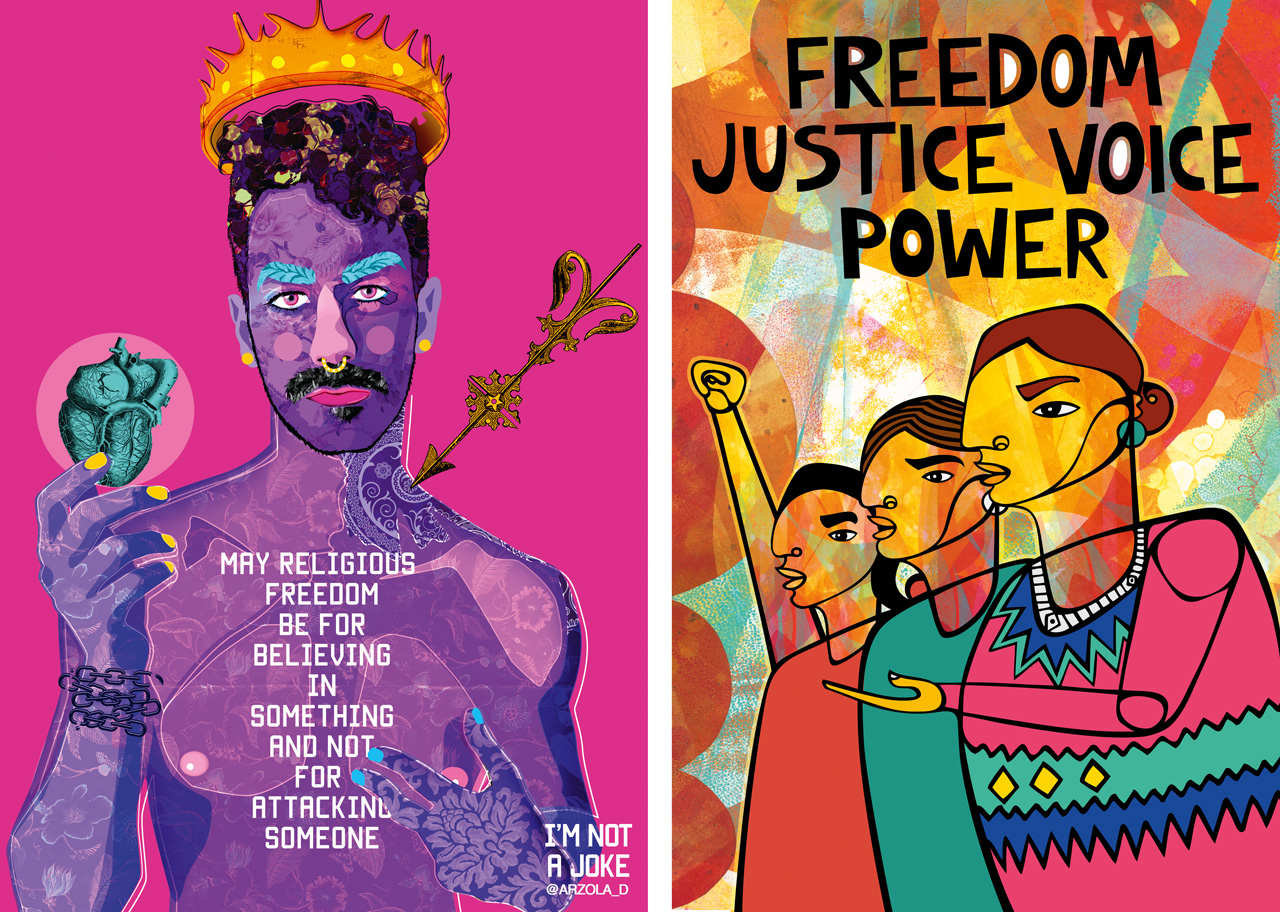

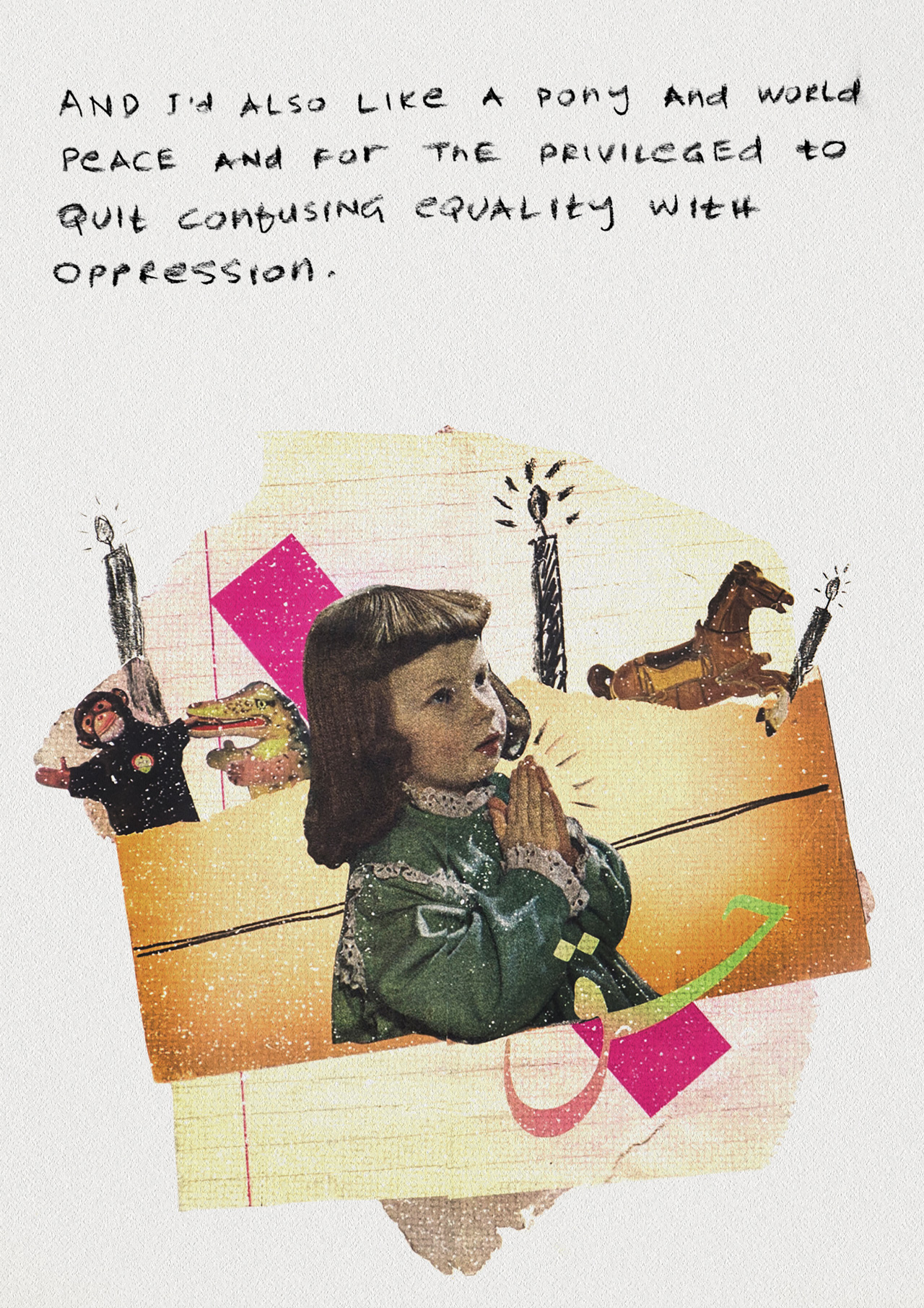

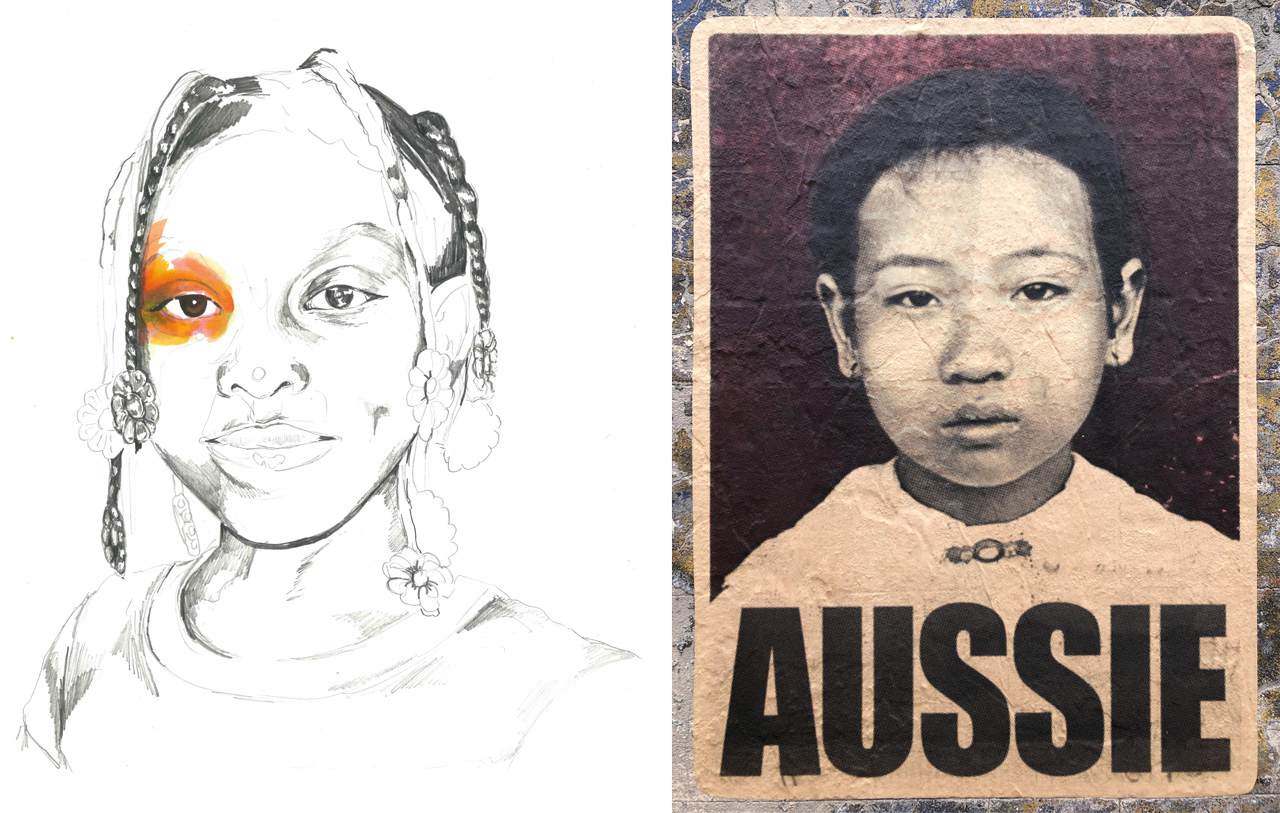

Engaging with audiences against a backdrop of institutional closures has encouraged artists to look at more inventive ways to exhibit work. For Venezuelan artivist Daniel Arzola, a long-time advocate of showcasing work in public areas, the changing museum and gallery landscape is further proof that traditional arts spaces need a reboot. “Museums and galleries continue to be spaces of great hierarchy that often respond to the art market and end up being exclusive and elitist,” he says. “In some cases, they exhibit works that can only exist within those spaces, but true art does not need a museum to be recognised as art. A piece of art has the power to transform the space it occupies. A mural can transform a building, a poster can change a bus stop. Art can resignify spaces.” It’s a sentiment shared by Pakistani-American satirical artist Safwat Saleem. “The traditional gallery system has shown itself to be rather inadequate and outdated. Lack of privilege and access limits the reach of so many incredible artists that deserve to be seen,” says Saleem. “These conversations are hopefully normalising the idea that artists can work outside of the traditional gallery system and go past the gatekeepers to take their work straight to the masses.” It is echoed by California-based artist Favianna Rodriguez. “The current systems are in need of major reinvention. In some instances, we need to let the old institutions die so that new ones can be born,” says Rodriguez. “The reality is that the entire arts infrastructure has been set up to advance the voices of white men and white male artists continue to dominate museum collections and gallery spaces. I don’t think the traditional gallery system is built to hold this deep global transformation that we’re going through, in which more and more people are demanding to see the art of the global majority uplifted – that is, art by BIPOC [Black, Indigenous, and People of Colour] artists. The traditional gallery system, in most cases, is not adapting fast enough and that’s largely because they have not spent time establishing those relationships nor do they really understand the context of our work.” For Adelaide-born artist Peter Drew, whose Aussie poster series is exhibited on city streets throughout Australia, it is “essential for artists to explore new ways of exhibiting their work outside of the traditional gallery system.” “But it’s about more than creating an alternative space for art,” he says. “The context in which art appears is equal in importance to the content of the work. I put up my posters illegally on the street which creates a tension that you simply can’t achieve in a gallery because everything that appears in a gallery is sanctioned. There’s always that limitation. The street has its own limitations, like bad weather and the police, but mostly it’s a joy. Every day I meet people who’d never think of visiting an art gallery and they see my posters. We talk about the history of this land and the conversation moves forward, little by little.”

We are standing at an inflection point with a chance to see the post-pandemic ‘new normal’ not as an illustrative term to describe where we are, but rather as a means of proactively shaping a new future; not just holding up a mirror to society but wielding a hammer to shape it; seeking comfort, not in the unchallenging ignorance of the past, but in the opportunity to do better.