News feed

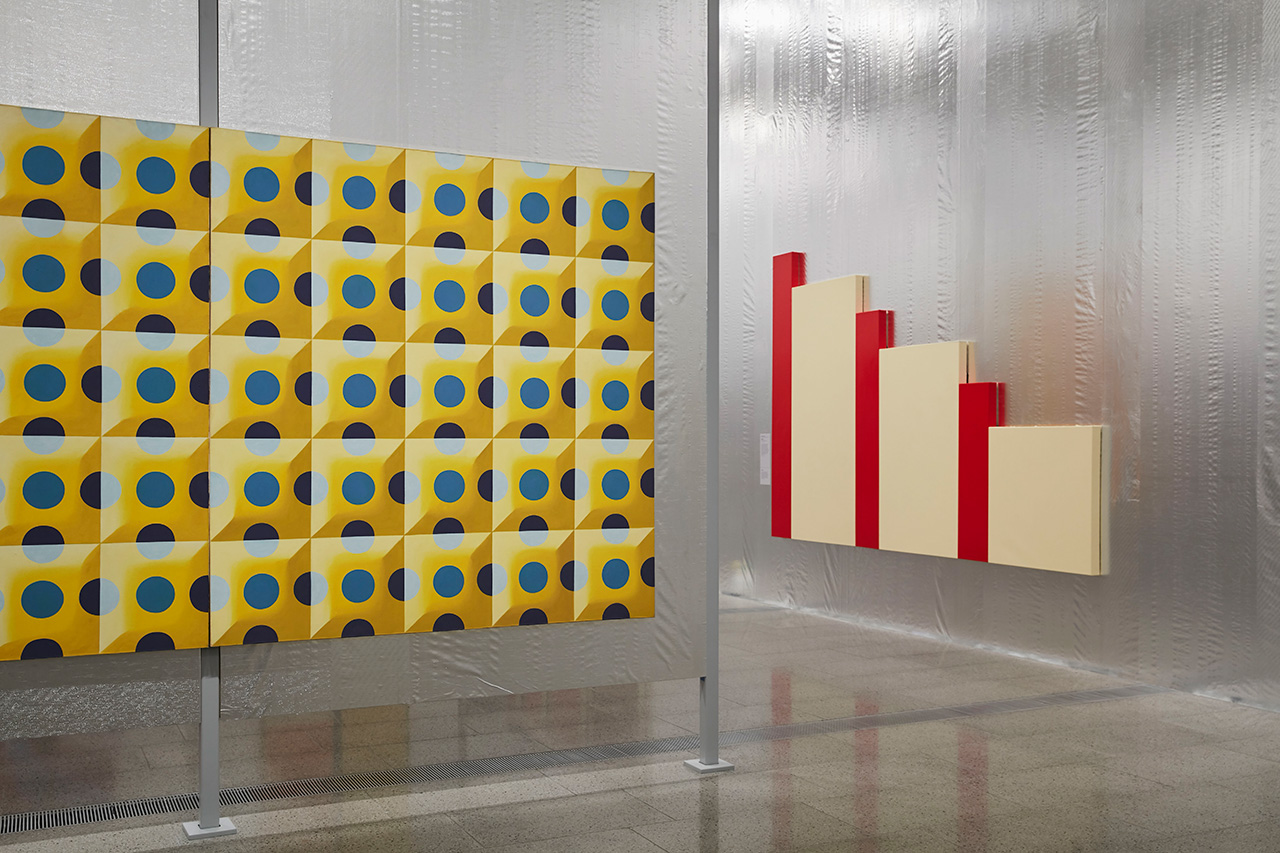

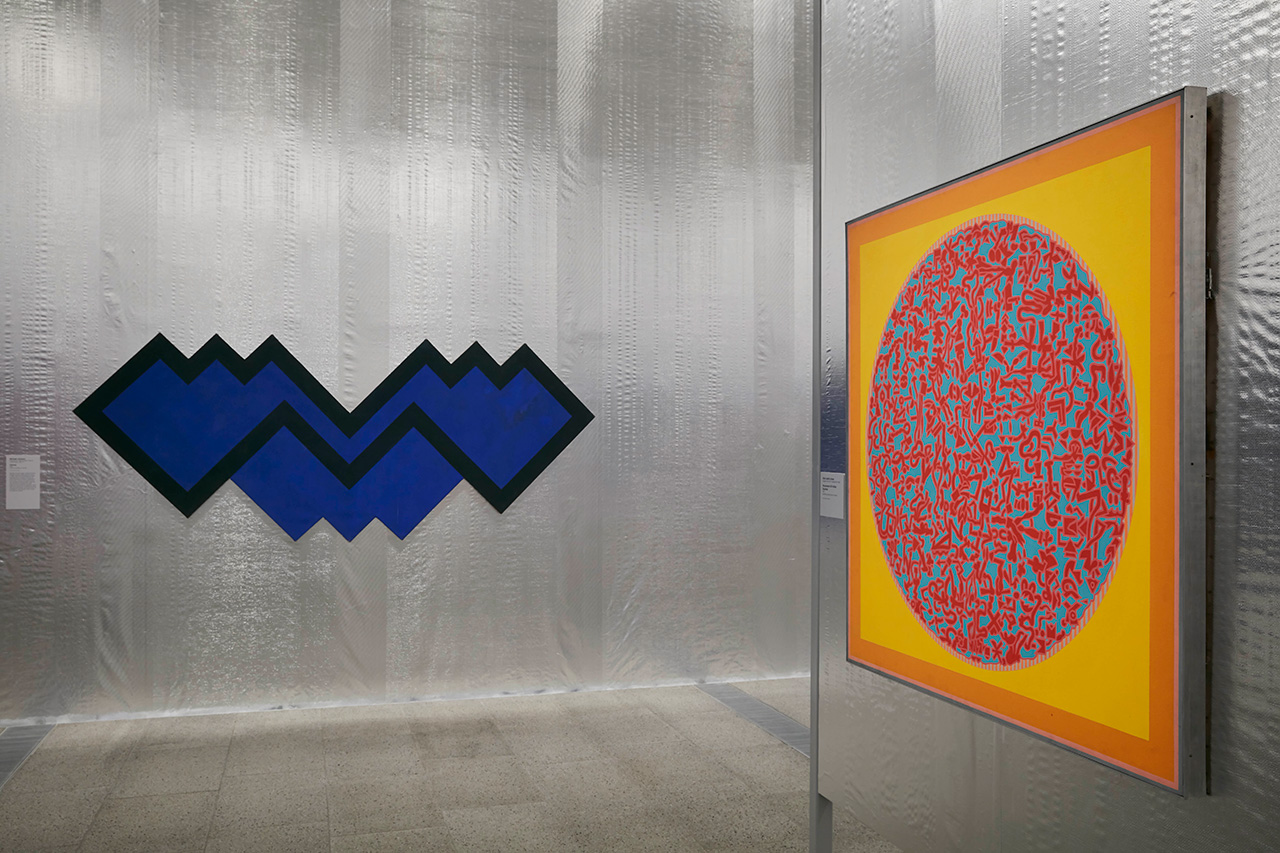

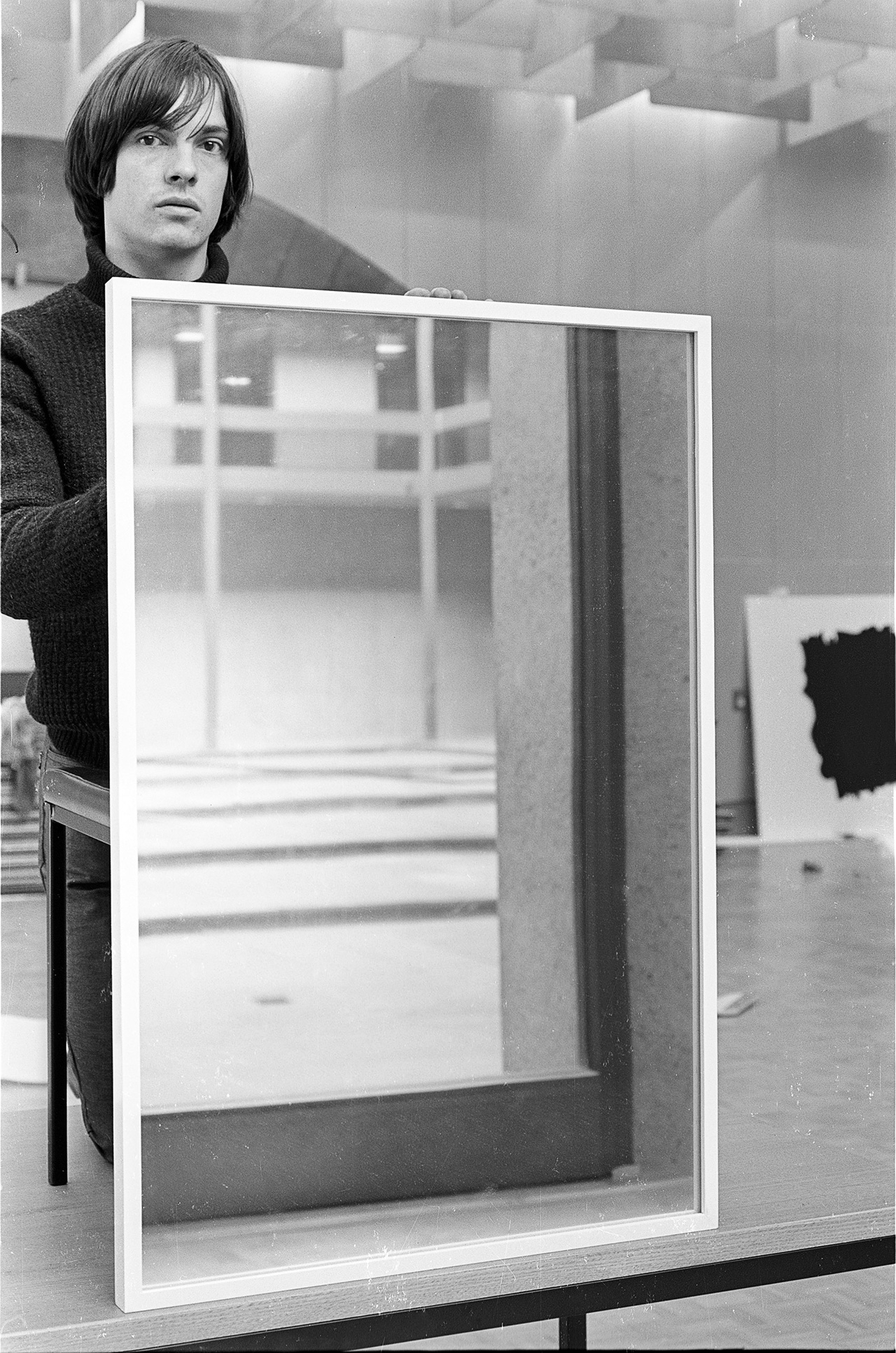

When The Field opened as the inaugural exhibition at the National Gallery of Victoria’s new premises on St Kilda Road in 1968, it was something of a conscious and contemporary counterpoint to the remainder of the gallery’s permanent collection. Prior to the opening, one of the exhibition’s curators, John Stringer, travelled to America as part of an enviable nine-month sabbatical. There, he visited Andy Warhol’s Factory in New York, a veritable hotbed of counter-establishment ideas that challenged prevailing notions of what art should and could be. Stringer would later return to Melbourne not only with Warhol’s silver foil covered walls at the front of his mind, but with the genesis of an exhibition that would be come one of Australian art history’s most radical propositions: a boundary-pushing exhibition that served as the first comprehensive display of colour field painting and abstract sculpture in the country.

According to Beckett Rozentals, Curator, Australian Painting, Sculpture and Decorative Arts at the NGV to 1980, the staging of The Field catalysed debate regarding the course of Australian art. To put it lightly, the exhibition was divisive and its reception reflected the disruption that it provoked in many. For its detractors, The Field’s then-esoteric focus seemed as odds with the Gallery’s new premises, particularly, Rozentals says, for those accustomed to the prevailing style of figurative painting and the remainder of the gallery’s predominantly historical collection.

“The 1960s saw a new generation of artists emerge across the country, many of whom had begun to look at artistic styles that had developed overseas, such as hard edge, colour field and geometric abstraction,” Rozentals says. “The Field artists were the face of this new generation, and were defined as the new abstractionists.”

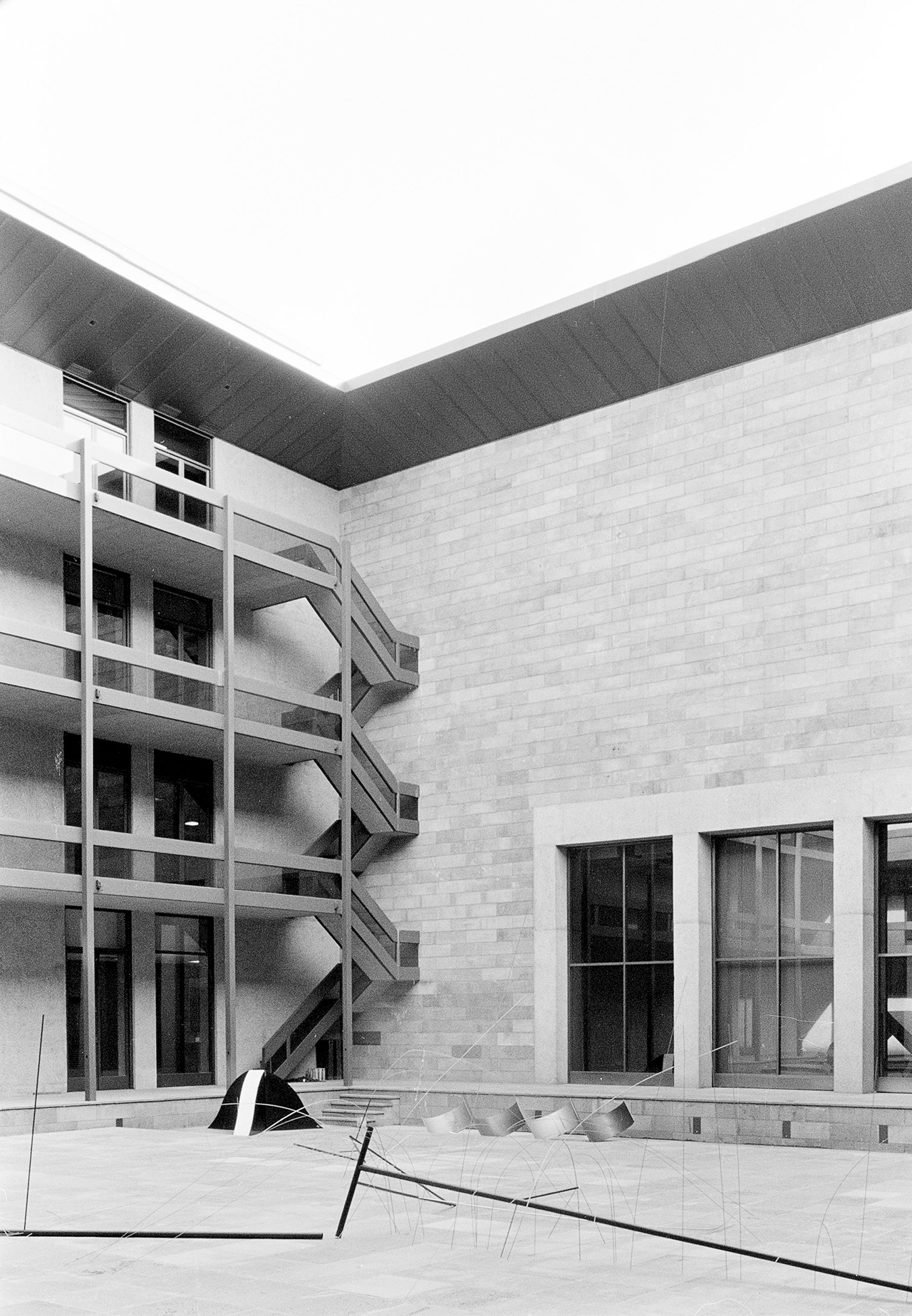

To commemorate the exhibition’s 50th anniversary, The Field Revisited sees the gallery recreate this watershed exhibition for contemporary audiences at NGV Australia at Federation Square. Showcasing as many of the 74 original artworks as possible, The Field Revisited has been co-curated by Rozentals in collaboration with Tony Ellwood, Director of the NGV. As this contemporary endeavour is a faithful recreation of the original, Rozentals says that “it only seemed right to use the same wall treatment” and geometric light fittings that provided the perfect environment for the groundbreaking exhibition in its original iteration.

While much of the the contention surrounding The Field played out publicly in the media, few proponents of ire were as vocal as Melbourne’s The Herald newspaper art critic, Alan McCulloch, who Rozentals says had been a key supporter of the preceding generation of Australian artists to whom the exhibition provided such a marked contrast. The Field launched the careers of a generation of young Australian artists, including Sydney Ball, Peter Booth, Janet Dawson and Robert Jacks, many of whom were influenced by American stylistic tendencies of the time. Eighteen of the exhibiting artists were under the age of thirty, with the youngest, Robert Hunter, just 21 years of age. Shortly after the opening of The Field, McCulloch lamented that the exhibition could prove to be a harbinger of “a continuous programme of similar shows,” fearing that “It then represents not just an ephemeral gesture, but a serious threat to the emerging creative spirit which during the last fifteen years has been given distinct and promising identity to Australian painting.” The art patron John Reed, amongst others, also spoke out against McCulloch in favour of the artists’ freedom of creative expression, stating that his remarks revealed “an unfortunate lack of contact with an important section of the creative world, which is supposedly his area of activity.”

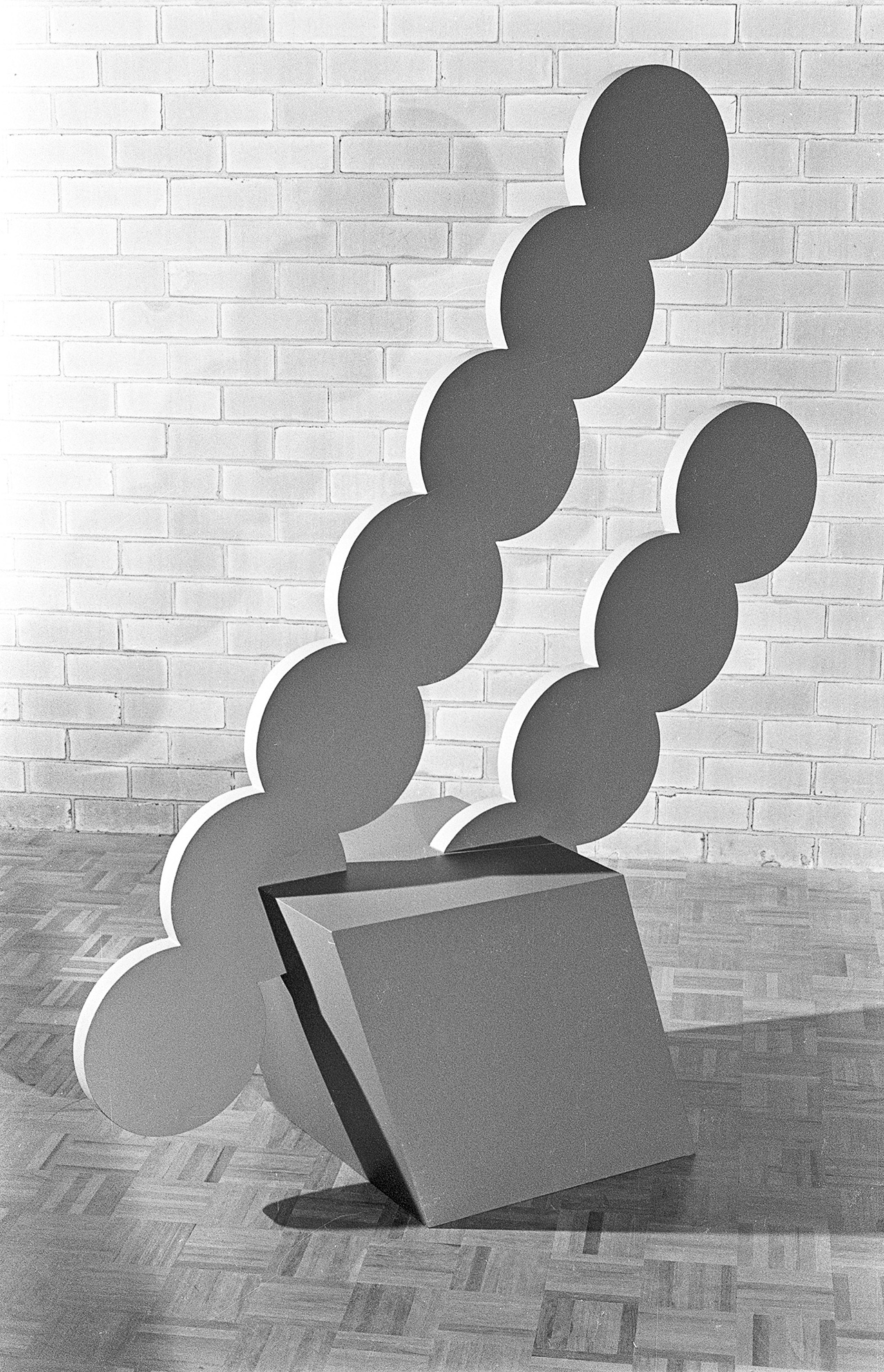

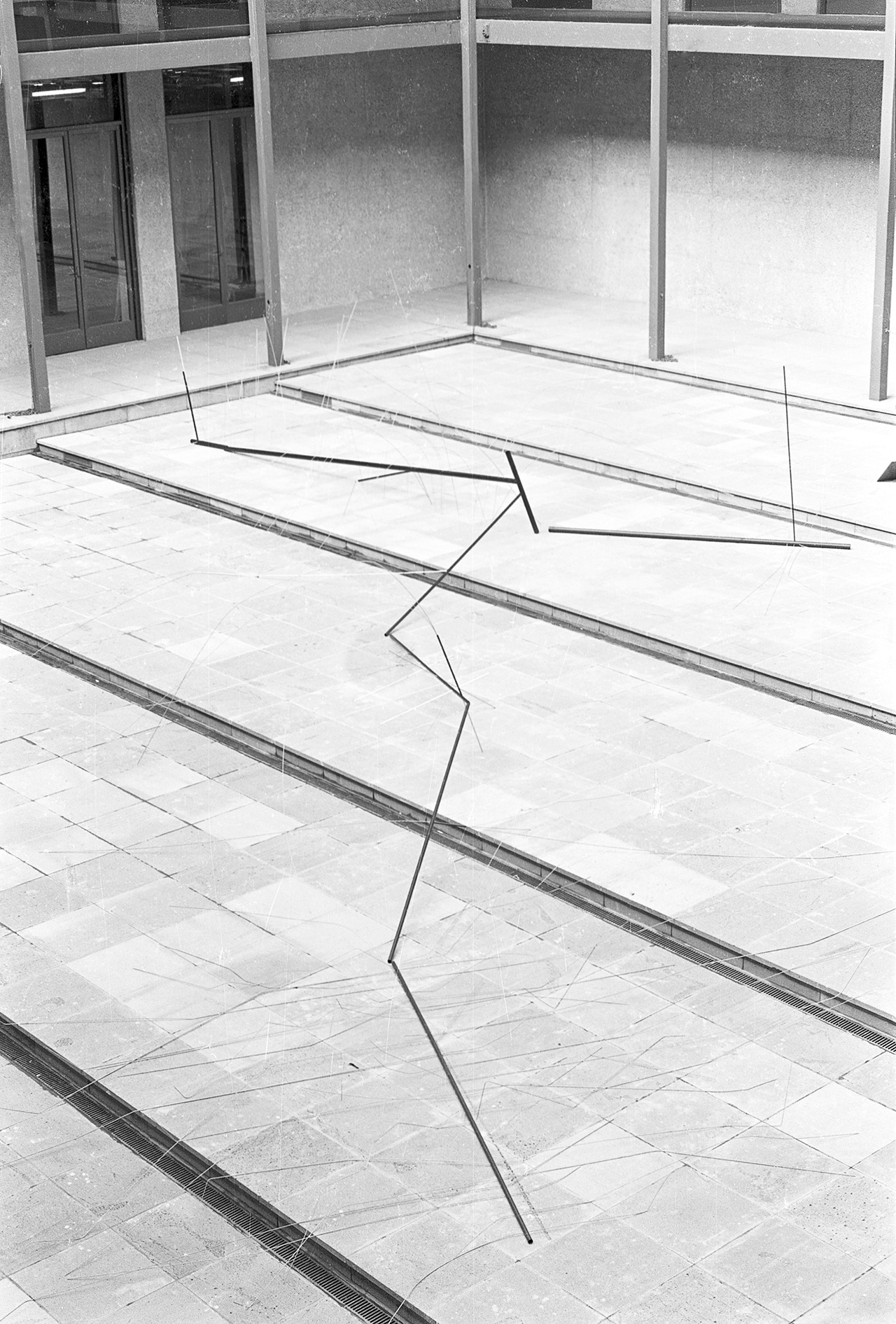

A number of works from the original exhibition have been lost to time, have since been destroyed, either by the hand of the artist or by accident and the fates of six paintings and six sculptures once featured in The Field remain unknown. Rozentals concedes that it’s difficult to say why it’s impossible to account for their whereabouts, but to account for their absence, the physical spaces of the destroyed and missing works are marked in The Field Revisited with to-scale greyscale reproductions throughout the exhibition space. Some, however, are tragically easy to account for. Rozentals says that sculptures created by Emanuel Raft and Nigel Lendon were “damaged in house fires, and two of Col Jordan’s works were damaged beyond repair while moving from Wollongong to Sydney in the 1970s. Normana Wight found that after the exhibition toured to the Art Gallery of New South Wales, there was little interest from institutions or private collectors in acquiring her painting. A large shaped canvas measuring 360.5 x 152.5 cm, Wight stated that she could not live around a painting, and subsequently cut it into pieces, taking it to the local incinerator to be burned. Trevor Vickers swapped his work Untitled painting 1968, constructed out of three red and three yellow canvases bolted together, for Sweeney Reed’s 1956 Plymouth. Reed later dismantled the work, effectively destroying it, and the pieces eventually went missing.”

Several of those artists, including Jordan, Wight and Vickers, were commissioned by The NGV with recreating their works for The Field Revisited, which of itself is not an entirely new concept where the remarkable history of this show is concerned. “A number of artists have recreated or coordinated the recreation of works before The Field Revisited was conceived,” says Rozentals. “The first work recreated took place between 1968 and 1969, when Janet Dawson recreated Wall 1968, originally painted on composition board, on canvas before the National Gallery of Australia acquired it.”

In the remainder of its re-staging, Rozentals and his collaborators at the gallery have stayed as faithful to the original presentation of The Field as possible. “There have been some challenges,” Rozental concedes. “The original gallery space no longer exists, and we have less than ten images depicting the interior of the 1968 exhibition (the larger sculptures were exhibited in the courtyard). I worked with the NGV Design team, who built a model of the original gallery space and scaled images of the seventy-four paintings and sculptures. We then used the photographs recreate the 1968 exhibition. I then transferred the 1968 layout to 2018 model. By doing this, we were able to maintain relationships between the works as closely as possible.”

Exhibiting for the remainder of the week and closing August 26, The Field Revisited offers audiences the chance to witness firsthand – or as close as possible to firsthand – a show that retains its potency as one of Australia’s most daring curatorial feats, the significance of which has not diminished with time. “The Field proposed a new direction for the Gallery, one that was committed to the avant-garde,” says Rozentals, accounting for its lasting impact. “The Field has contributed to the significant place abstraction continues to occupy within contemporary Australian art, and to the recognition that the public art gallery can be a place where expectations are challenged.”

The Field Revisited is on display UNTIL August 26, 2018 at Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia at Federation Square. Entry is FREE. More information is available here.

Tile and cover image: Courtesy of the National Gallery of Victoria