News feed

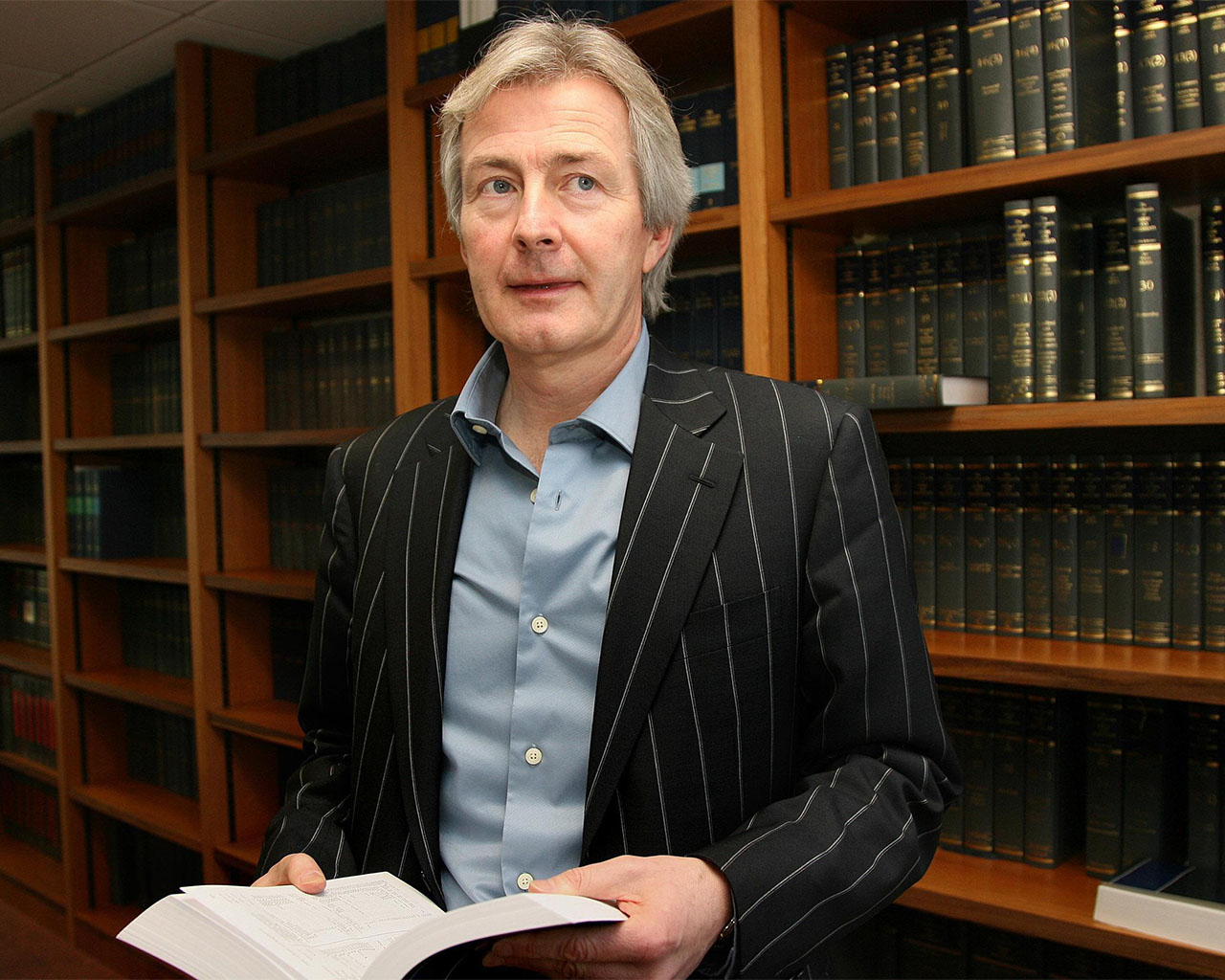

Paul Tweed is in a feisty mood. The Northern Irish attorney has built a reputation as one of the most formidable defamation lawyers in the world, with a client list that reads like a who’s who of the last 20 years’ biggest celebrities. Liam Neeson, Justin Timberlake, Jennifer Lopez, Ashton Kutcher, Nicolas Cage, and Harrison Ford – as well as many others – have all contracted his services. Thanks to his unique skills, they’ve all emerged the better for it, with many of the biggest media corporations in the world being forced to withdraw stories, issue apologies, or make substantial payouts after Tweed put on the pressure. In 2006, he even forced the National Enquirer to publish an apology, after successfully representing Britney Spears in an action against the tabloid: it was the first apology issued by the publication in its 96-year history.

Now 65, but fizzing with the energy and enthusiasm of a man half his age, Tweed is setting his sights on a bigger target.

“As the media changes, then obviously my job changes dramatically,” he says. “The likes of Amazon—these are the big battlegrounds now.”

It’s not just Amazon that has attracted Paul Tweed’s attention. He’s taking on the biggest, most powerful corporations in the world.

“Most of my work now is against social media—Facebook, Twitter, the search engines that have established European headquarters in Dublin,” he says. And, with something approaching glee, he points out that it’s precisely this tax-savvy move by the big tech companies that have exposed a chink in their armour.

In 2010, President Obama introduced the Speech Act, which stipulated that a U.S. citizen cannot sue a fellow citizen or U.S. corporation outside mainland U.S.A. Although it was designed to stop the so-called “libel tourism” that helped make Tweed’s name, he now believes he can use that same Act to target the social media companies.

“If they’re based in Dublin, we can sue them,” he says. “And most importantly for an L.A. client, so can they. The Speech Act had a sobering effect. But along come Facebook and Twitter and Google and suddenly it is tax tourism, not libel tourism. They had to form Irish companies to take advantage of the favourable Irish corporate tax regime so the Speech Act suddenly doesn’t apply. They’re not an American company any more. And that was a big ‘whoops!’ for them.”

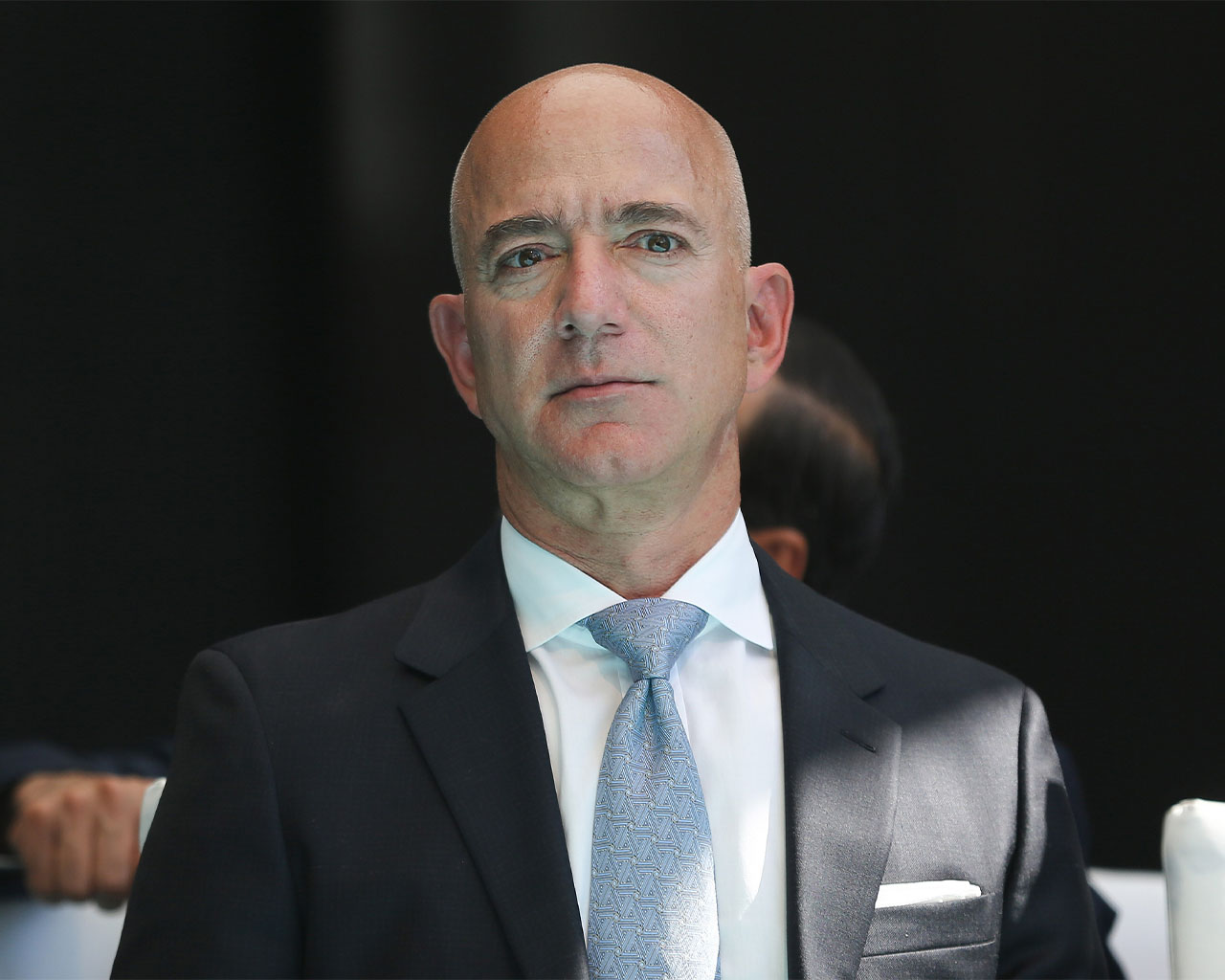

One might think that challenging Jeff Bezos or Mark Zuckerberg—men with hundreds of billions in the bank, as well as a wealth of largely unchecked power—would be a frightening prospect (or at the very least, might make most people think twice about starting a fight with them). But not only does Tweed relish a good scrap, he’s also no stranger to the underhanded tactics occasionally employed by those who believe they’re above the law.

“I prefer not to go into names, but there are people who have tried to take me out before now,” he says. “Simply because they don’t like what I did to them, not because I did anything wrong.

“There’s always going to be that threat they can squash you because of sheer financial power and might. I don’t know if they will or not. I’m taking on governments who I know are doing very, very naughty things to try and undermine me. There’s one particular government and they will do everything they can and I may not be able to resist that, you just don’t know… but you’ve just got to keep going.

“And you know what? Once they do that to me, once I know they’re doing it, that’s like a red rag to a bull to me, and that might end up being to my loss… but then on the other hand, it might be their loss.”

Tweed credits this gutsiness to his upbringing in 1970s Belfast—at that time ground zero for what was known as “the Troubles” between those fighting for a unified Ireland and those who saw Northern Ireland as part of the United Kingdom. Bombings, shootings, paramilitary activity and terrorist attacks were part of daily life in Belfast during that period, with violence perpetrated on both sides of the divide.

“You know, I’ve been there. I’ve done it all. I was brought up in Northern Ireland. I was a child of the Troubles. We had bombs going off all the time,” he says. “During the Troubles you never knew what was going on, one day to the next. I remember there was one scenario where a New York attorney called me and he said, ‘Once I get you in court…’ and at this particular stage there was chaos going on in Belfast and I was like, ‘Ooh I’m trembling in my boots, what are you going to do…?’”

Born in the seaside town of Bangor, just 13 miles from Belfast itself, Tweed confesses he didn’t initially consider law as a career at all. Describing his upbringing as “lower middle class,” he also claims to have “scraped through” school, before his mother, who was a legal secretary, suggested studying law.

“And that was it,” he says. “I went to Queens University in Belfast by the skin of my teeth, and got out by the skin of my teeth—and then I struck lucky: I answered a job in a local newspaper and joined a firm that specialised in conveyancing and probate and company law.”

He lasted a month before growing bored, and after applying for a series of positions he now describes as “optimistic”—including Governor of the Solomon Islands and as a corporate lawyer in the Cayman Islands—he began to make a name for himself in insurance law. Typically, that initial success came from a combination of charm, skill, and sheer ambition.

“I built up about 13 insurance company clients in nine years, mainly by entertaining claims managers. I was paid very little and had a huge overdraft. Looking back I was mad,” he recalls. “I used my own money entertaining these guys and building up that practice; it took me years to pay back. And then I got the ‘cream bun case’ and everything changed.”

The “cream bun case” might be described as the moment Paul Tweed found his calling—and contains the unique mix of tabloid shenanigans and justifiable outrage that has defined much of his work since. In 1985, the Sunday World newspaper in Northern Ireland ran a story ridiculing how two of the country’s most eminent senior barristers had been seen fighting over the last chocolate éclair in a Belfast cake shop.

It was funny. The only problem? It also wasn’t true. Rather than laugh it off, the barristers instead hired Tweed to represent them in a libel action against the Sunday World. The highly-publicised case ended up being settled by a jury, and the paper was forced to award nearly $70,000 in damages to each of them.

From there came another high-profile case, representing the boxing promoter Barney Eastwood against former world champion Barry McGuigan. That case resulted in a $625,000 payment, the largest libel award in Northern Irish legal history.

But it was after he successfully forced the National Enquirer to publish their 2006 apology for falsely suggesting that the marriage of Britney Spears and then-husband Kevin Federline was on the rocks that Tweed’s new status as defamation lawyer to the stars was cemented. Before the Speech Act, his trick was to argue that in the modern, ultra-connected age, the parent location of a magazine’s publisher was effectively irrelevant—meaning his U.S. clients could sue in a British or Irish court, where they were more likely to get a result than they might in an American court.

Among the most high-profile was a case brought against Bauer, publishers of Heat magazine, which had printed photographs of Justin Timberlake and a mystery woman, along with a suggestion that he was cheating on wife Jessica Biel behind her back.

“There was a front-page photograph of him dancing in a clinch and they were trying to make out it was some clandestine love affair he was having at Jessica Biel’s expense,” he explains. “We brought the case in Dublin. Justin Timberlake and Jessica Biel have a worldwide reputation so it doesn’t matter whether it’s LA, Ireland, England, or wherever from a point of view of reputation. And from the point of view of publication, there’s the same number of Heat magazines in a supermarket in Dublin as there were in a supermarket in London.”

Tweed won again, before the High Court in Ireland with Bauer apologising. Further big-name clients followed Timberlake across the Atlantic, and the Belfast lawyer was suddenly on first-name terms with celebrities including Sylvester Stallone, Johnny Depp, Reese Witherspoon, Kelsey Grammer, and even Prince Andrew. The contrast between the local boy made good and the A-listers occasionally made for surreal scenes.

“I remember ABC News did a piece on me. It was in 2006, at the time of the J. Lo and Britney stuff and they did a thing: ‘Why are they all coming to Belfast?’” he says. “And they interviewed someone in front of the City Hall in Belfast and said, ‘Why is Britney Spears coming to Belfast to see Paul Tweed?’ and she hadn’t heard of Britney Spears but she had heard of me.”

He also maintains that despite such glittering company, he has never had his head turned by the trappings of fame.

“Oh Christ no, I’ve never been starstruck. That wouldn’t be my gig at all,” he says. “I normally bore the pants off them before they can actually get close enough to me. Some of them probably don’t remember my name—I’m just a service provider to them.”

He does concede, however, that he has remained friends with Liam Neeson, Tom Cruise, Uri Geller, and Sarah Ferguson. Perhaps more intriguingly, he notes that he is most definitely not friends with an unnamed “world famous musician.” Naturally, he won’t disclose who, exactly.

In addition, Tweed is keen to stress that his cases are not taken purely on the strength of celebrity. The bottom line remains the same as it did when he was a struggling insurance lawyer in 1970s Belfast: If Paul Tweed doesn’t think he’ll win, he won’t take the case, no matter how big the names involved, or how much publicity it might attract.

“The most important thing to me is my reputation,” he says. “If I lose a case my credibility goes and this goes for all lawyers. You’re putting your neck on the line. I think I turn down at least eight out of every ten people who come to me, maybe more. And I do it in the interests of the client as well.

“If the first question anyone asks me is, ‘How much do you think this is worth?’ that’s a big red warning light going off for me, sirens going everywhere. You do not litigate for money. You litigate to get your vindication, to get it taken down, to get an apology and a clarification. And if to strengthen that apology you need money, then so be it, but that should be way down on your list.

“You know, people think that just because something’s false, or wrong, that they’ve got a libel action. And that’s not the case at all. I always say to someone, ‘You think you’re worried now about the damage to your reputation? You wait till you’re six months into legal action. That’s when the real worry comes in’.

“You’ve got to try and understand the psychology that goes through my mind the whole time. Because I’m trying to think maybe six months ahead. I have to work out, this client, is he going to be able to last the pace? If he’s starting to panic now, if he’s ringing me every 20 minutes now, what the heck’s he going to be like later? So maybe it’s really not in his interests to take the case on.”

Of course, when you’re a Hollywood A-lister used to having your every whim indulged, being told ‘no’ by a lawyer from Northern Ireland doesn’t always come easy—even if it is done in the nicest possible way. “I’ve had someone threaten to report me to the Law Society because I wouldn’t take them on,” he laughs. “But at the end of the day I’ve been there, done that. The funny thing is I still take the view that because I’ve come from nothing, even after 40 years I’m really flattered every time a client comes to me, even if I end up not taking the case.”

For now, Tweed’s focus is very much moving away from the print media that made his reputation and towards the new media giants. With studies showing that some 80 percent of 17- to 23-year-olds in the United States get their “mainstream” news from Facebook, he is concerned that the social media platforms are failing to accept any responsibility for what they publish.

That fake news abounds on the likes of Facebook, Twitter and YouTube is well-known; but, as Tweed argues, just because it happens doesn’t mean it should be accepted. Moreover, if some of that fake news includes libelous or defamatory comment, then he believes the platform hosting it should be held as accountable as any newspaper or magazine would be.

“They’re not regulated in any way at all,” he says. “They say, ‘we’re a platform, we’re not a publisher’. So that’s the battleground. If a newspaper publishes a letter from a member of the public, the newspaper is liable for anything defamatory in that letter. So how can Facebook say, ‘well we’re just a platform, we’re not liable for anything posted on there’? These people, these companies – they’re too powerful already and it’s becoming almost too late to get them under control.”

But the boy from Belfast who grew up amidst the bombs and balaclavas of the Troubles isn’t about to be intimidated by any dotcom billionaires. Trying to rein in the out-of-control social media giants has become Paul Tweed’s new passion.

He may have made his reputation as the world’s sharpest defamation lawyer thanks to a host of household names (and a cream bun) – but his real legacy could still be to come. Bezos and Zuckerberg would do well to watch out.

“I love the hunt,” he says. “And I love getting solutions, I love coming up with stuff that other people just wouldn’t do. I just don’t like the threats, y’know? If someone threatens me, that’s when I really get started. My mother used to worry about that, because I can never settle, it’s a character flaw. I don’t let the bone go, no matter what it is.”