News feed

Aged just 15, Daniel Arzola was tied to a pole, attacked with cigarettes, and threatened with being burned alive by his homophobic neighbours in Maracay, Venezuela. As a young man with a keen interest in art, he was also forced to watch his drawings be destroyed. The trauma of the event saw Arzola retreat from his passion for many years.

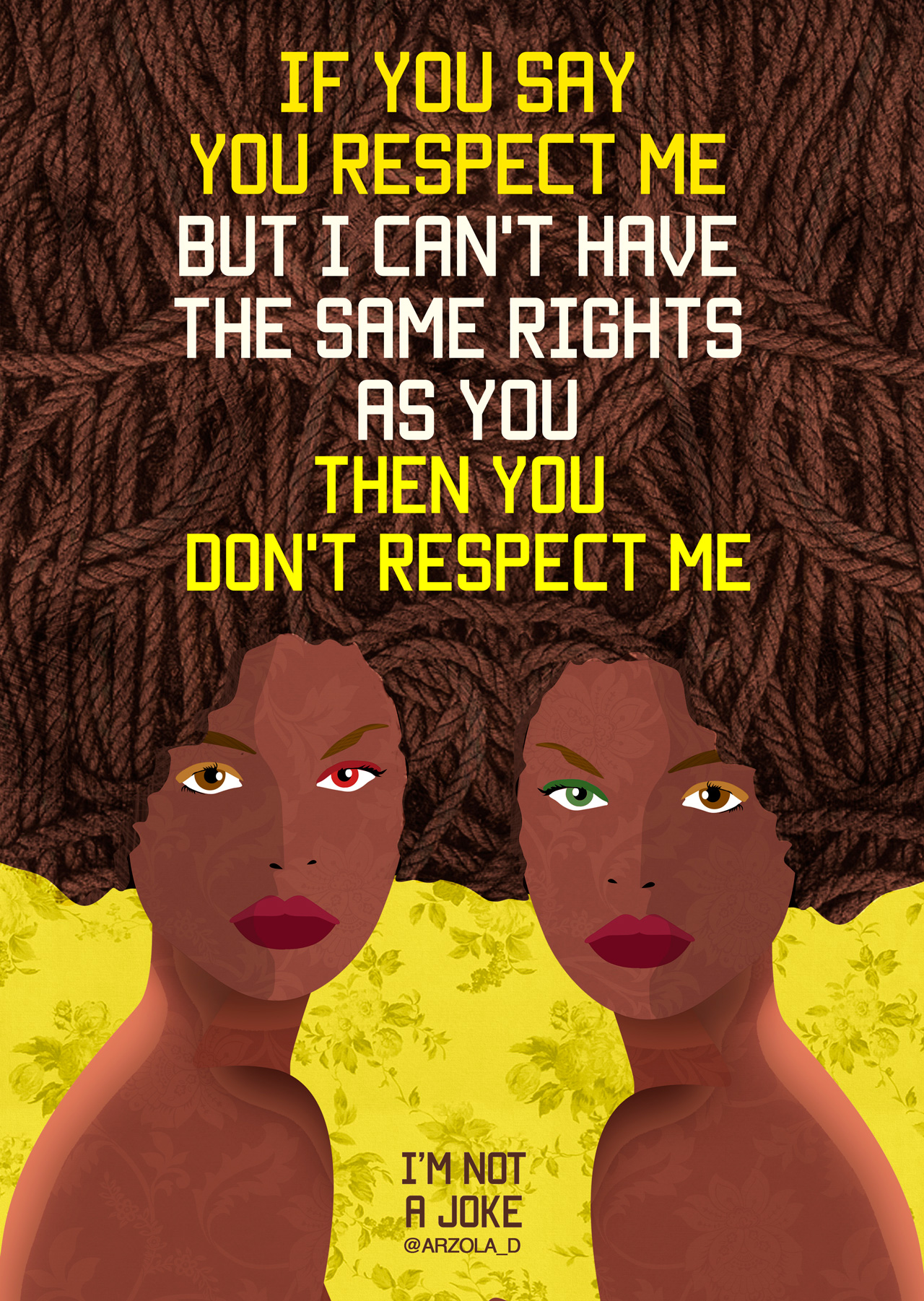

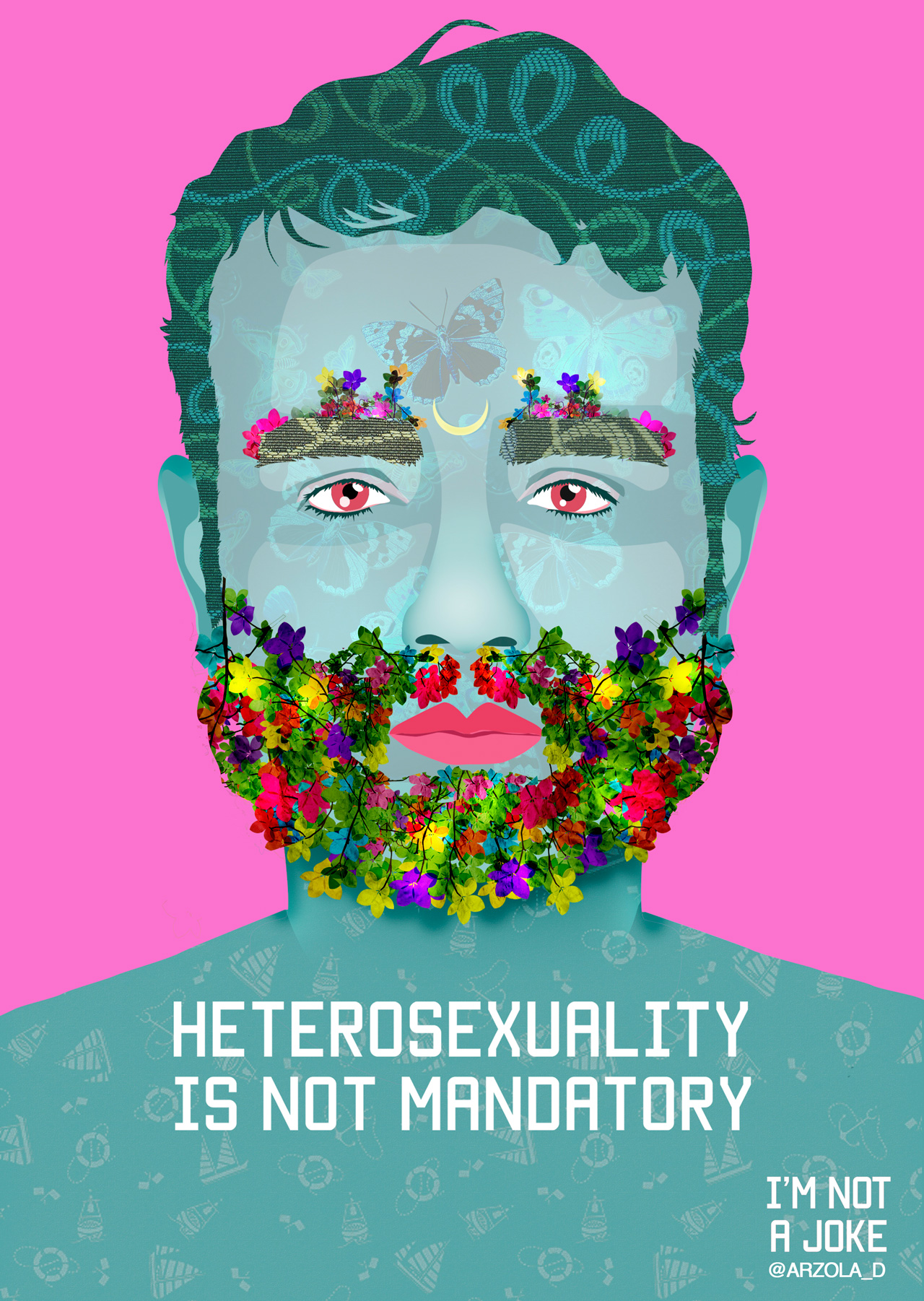

Delving deep into the artist’s personal experiences, which include being the target of hate crimes on multiple occasions, Arzola’s contemporary work explores notions of gender and LGBTIQ+ rights. No soy tu chiste (‘I’m not a joke’), a series of posters featuring colourful illustrations alongside powerful messages that address complex issues around civil liberties and identity, works to combat stereotypical depictions of the LGBTIQ+ community. Slogans such as “If you say you respect me but I can’t have the same rights as you then you don’t respect me” reaffirm an individual’s right to, above all, dignity, and act as a form of resistance to oppressive societal norms.

Having had much of his physical artwork targeted by bigots, Arzola turned to the digital landscape to give his work a permanence and safety not afforded by paper. “Growing up in Venezuela my work was destroyed many times,” he recalls. “I came to understand that art can be fragile. Now that my work is digital, however, it has become more accessible than ever before because you can destroy the medium, but the artwork can be reproduced again, here or anywhere else in the world. In that way, the message lives on and the work becomes indestructible. That is ‘Artivism’ for me.”

That notion of Artivism is key to Arzola’s work and one which has seen him garner social media praise from the likes of Madonna, Cyndi Lauper, and Katy Perry. “The basic idea of the word ‘Artivism’ has been shared since the end of the 20th century, referring to those artistic works that engage explicitly in a social context,” explains Arzola. “For me, art is always social because it portrays the behaviour of human beings as a response to, and evidence of, the different situations articulated by society. Art allows us to talk about who we are and where we have come from. It presents us with ideas that transcend and that enable us to share statements as a community. It needs to be accessible and it needs to be seen. A museum filled with works but never visited is just a tomb.”

Arzola acknowledges that accessibility in art remains an issue and continues to champion exhibiting outside of traditional gallery systems. “I grew up in a place without museums, cinemas, or art galleries,” he says. “But the internet changed those dynamics. I think I first got online when I was 13, and today it has become my main workspace due to how accessible knowledge and information are. Social media and the internet allow us to democratise art and bring it to everyone, connecting one or more worlds. One day Madonna may tweet the work of a young queer person who grew up in a poor neighbourhood of Venezuela. Then everything changes, because the dynamics that separated us disappear for a moment, and you, who had felt invisible all your life, suddenly feel that the world has noticed you, and this is the first step to growth.”

Since 2017, Arzola has also had a permanent exhibition, a 14-metre mural, on the Buenos Aires subway. “The station is named after Carlos Jáuregui, an activist for the civil rights of LGBTIQ+ people in Argentina. I think it is important to be able to feel represented in culture, in public spaces, to see that there are people like you facing similar situations. Art plays a fundamental role in the construction of our identity, especially in an age where the personal has become political,” says Arzola. “Art has the ability to spread the testimony of a person or a group of people and make it accessible to others. Art is knowledge. If we pay attention we will understand art as a testimony of the history of humanity. From Molière’s theatre to the art generated during the industrial revolution; from Federico García Lorca portraying the massacre of the Spanish civil war in his poetry; to the photography of Lewis Hine and his portraits of child labour; the Mexican muralism; the dancing artworks of Keith Haring during the AIDS pandemic, or a novel of Reinaldo Arenas showing the inferno created by Fidel Castro in Cuba. Art is social when it tells the realities we face together. It has the power to document the social struggles of our time. Art is political because it carries with it a message that survives whoever created it. History is usually written by those who won the war, for those who obtained power and didn’t want to share it, but art can be made by anyone, anywhere.”

Explore more of Daniel’s work on his website and instagram. You can also support his work on Patreon.