News feed

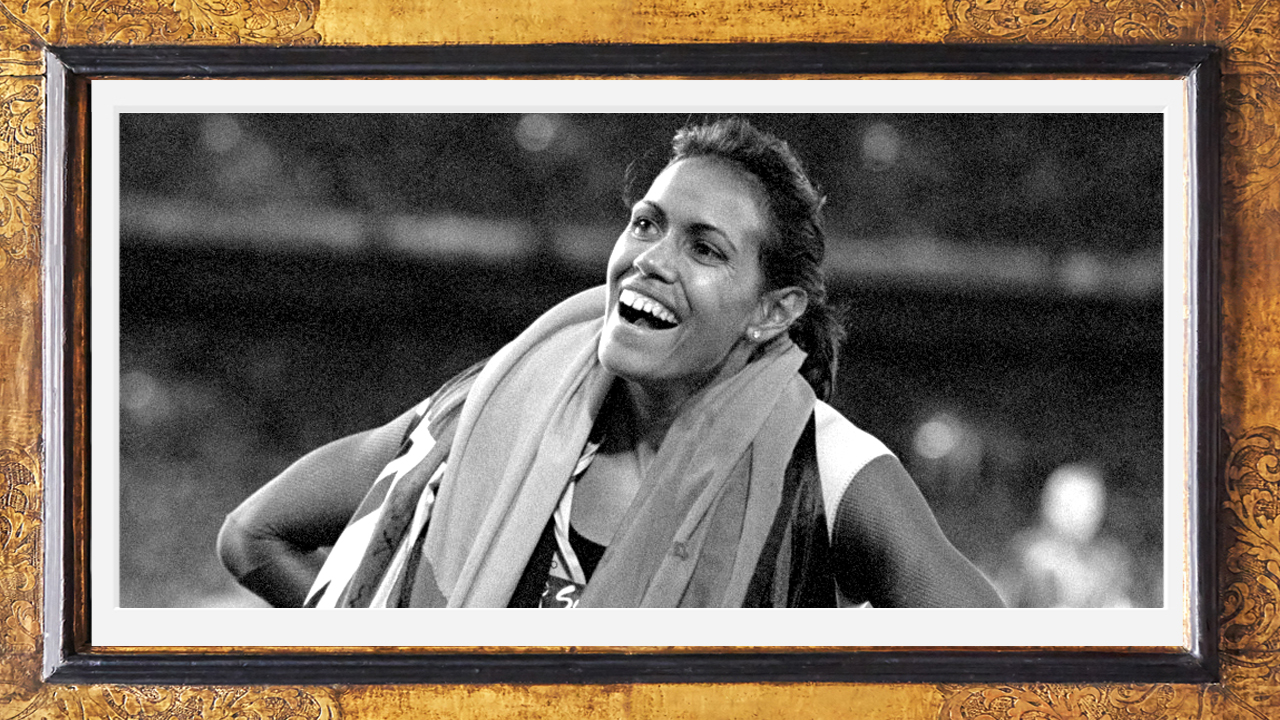

“The event you’re about to see is being called the race of our lives,” said a TV presenter ahead of the 2000 Olympic Games 400m finals, in which 27-year-old Aboriginal sprinter Cathy Freeman was competing. Not only was the tournament being held in Freeman’s home country—set in Sydney, Australia—but her story was one that was uniting the nation.

Just months prior, in May 2020, hundreds of thousands of Australians marched for a more reconciled country and for the recognition of the immense ill-treatment of its First People. Men, women and children adorned in red, black and yellow took to the streets on a cold winter’s day to walk across the Sydney Harbour Bridge. They waved Aboriginal Flags underneath the word “Sorry” scrawled across the sky.

Watching the YouTube footage of the race back now, 20 years on, it’s hard to believe Freeman held so much on her shoulders. With the crowd erupting and thousands of Australian flags being waved in the air, the camera zooms in on Freeman’s face. She’s deeply concentrated, aware she’s carrying the weight of a nation that so desperately needs something to unite them.

Moments later, to a stadium full of people celebrating her momentous win, Freeman would take her victory lap, holding high, as she did controversially at the 1994 Commonwealth Games, both the Australian and Aboriginal flags. “It seems like the whole of Australia has a smile on its face,” a commentator can be heard saying over the broadcast.

In September 2020, to mark the 20-year anniversary of her win, a documentary titled Freeman was released, detailing Freeman’s childhood, her personal reflections as an elite athlete and the broader impact of her journey on Australia as a whole.

“I was a kid who was quite embarrassed to be a Black kid,” she said in the film. “An Indigenous kid sort of grew up with that self-image. I could never understand why, whenever I smiled at someone, they wouldn’t smile back. I used to get really upset. I thought, why don’t people smile back at me! Quietly, it really devastated me.”

Of the moments before the race, Freeman said she felt her ancestors were watching over her. “I feel like I’m being protected. My ancestors were the first people to walk on this land. It’s a really powerful force,” she reflected. “Those other girls were always going to have to come up against my ancestors. For the first time, I feel the stadium, I feel the people, I feel the energy. I feel like I’m being carried. I know exactly what I need to do. I know how to do this. I can do this in my sleep. I can win this. Will win this. Who can stop me?”

Now, Freeman is still working to make a difference to young Indigenous children, hoping they too will realise their power. From Melbourne, where she lives with her husband and son, Freeman oversees the Cathy Freeman Foundation (CFF) which delivers educational programs to 1,600 Indigenous children across four remote communities: Palm Island, Woorabinda, Wurrumiyanga and Galiwin’ku.