News feed

Every day, the artist John Young downloads one thousand found photographs at random from the Internet. Were you to comb through his browsing history, you would find everything from travelogue sites mined for stock imagery to adult sites plumbed for their nudes. Overnight, a kind of automated algorithm – an ‘action’, for those of you familiar with the Adobe Suite – inbuilt to Young’s Photoshop program processes the images in batches using predetermined filters that abstract the original photograph to a point beyond recognition.

“The next morning, I have a thousand of what I call ‘drawings’,” Young says of the composites he is left with. “They’re all abstract forms but the colours are still there.” A photograph from the deserts of Alice Springs might share the same dusky and earthen palettes, but none of the signifiers of its original landscape are discernible. “All that’s left is that resonance,” Young says of the hazy scenes hanging before him. “Other than the glow behind the screen, which we can’t get, it’s totally faithful [to the original].”

Young has been refining this element of his studio process for 10 years now. The artist will then choose one of the thousand ‘drawings’ to translate from pixel and glass to oil paint and linen using traditional painting techniques. It’s something he describes as an act of “transition from the virtual image to a physicality again.” Where artists of the 20th century were only able to produce so many drawings in a lifetime, Young has the capacity to produce that same amount in a single night. The final act of breaching the divide between the virtual and corporeal worlds, however, takes slightly longer. It can take several weeks to execute a work on linen by hand, a process which Young sees as a means of slowly restoring the physicality of the subject, which by now has gone from its original form to an avatar, to an abstraction of that image, before it once again finds material realisation as oil on Belgian linen.

When it comes to selecting a subject from the thousands produced daily, Young’s process is deeply intuitive. “All I can say is that [the drawings remind me of the paintings that I’ve learned [about], it must be determined by the things that I’m educated [about]. The landscapes look like early American Modernist paintings; the [colour spectrums] are more mid-century.” The works in This is a Shelter, a new exhibition open now at Olsen Gallery, were adapted from images of colour spectrums, photographs of rainbows in particular. The forms are “pretty twisted,” says Young, but the colours are very similar; rainbows, naturally, are the first thing that comes to mind on viewing the works – that, and aura readings, or default iPhone screensavers.

This is a Shelter takes its name, in part, from the experience of viewing and absorbing the work itself. “It’s a shelter from the amount of virtuality we live in now,” says the artist. By introducing an element of the body to the works, Young invokes the shape of a cocoon. “It’s how we’re transitioning now into augmentation,” he says.

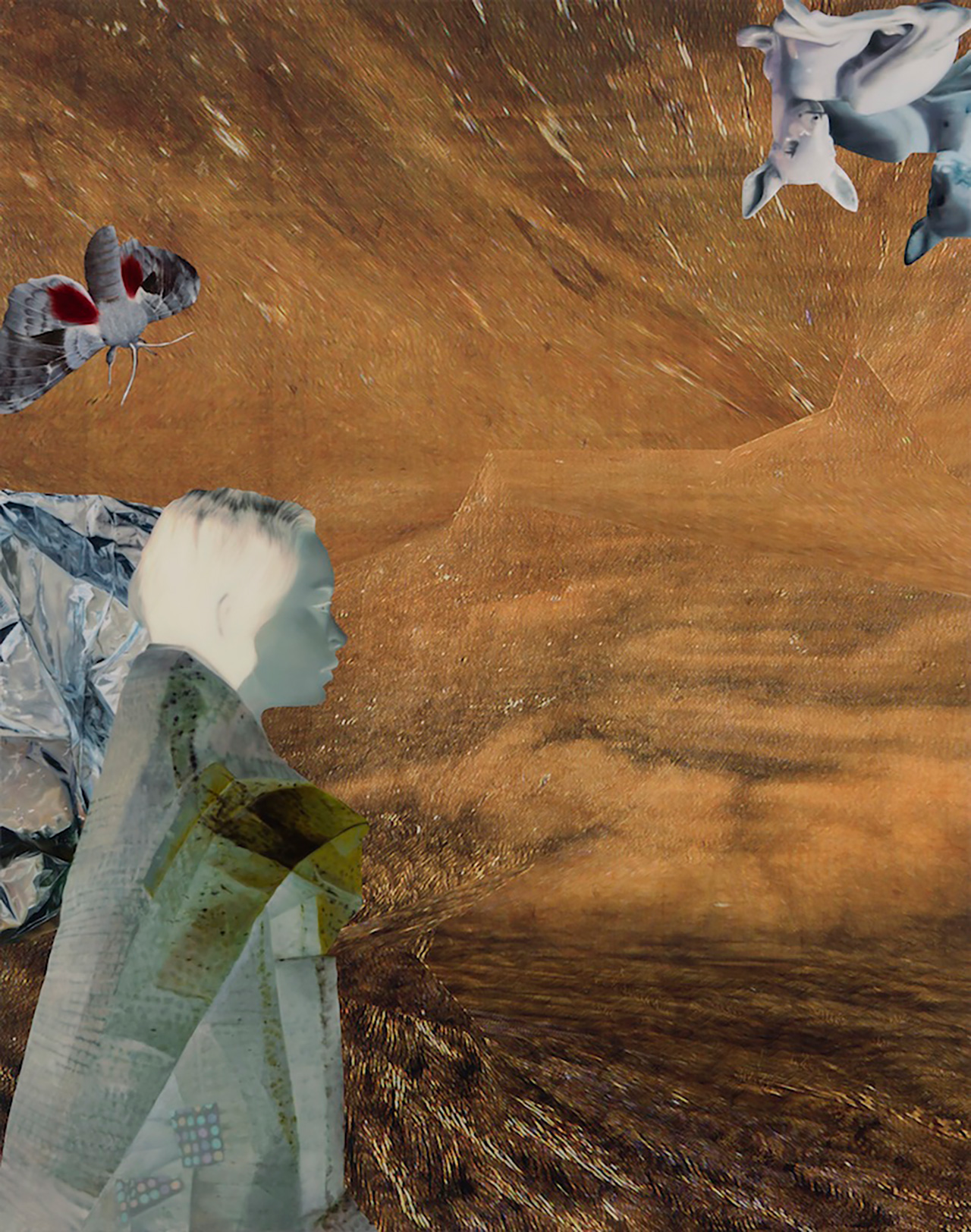

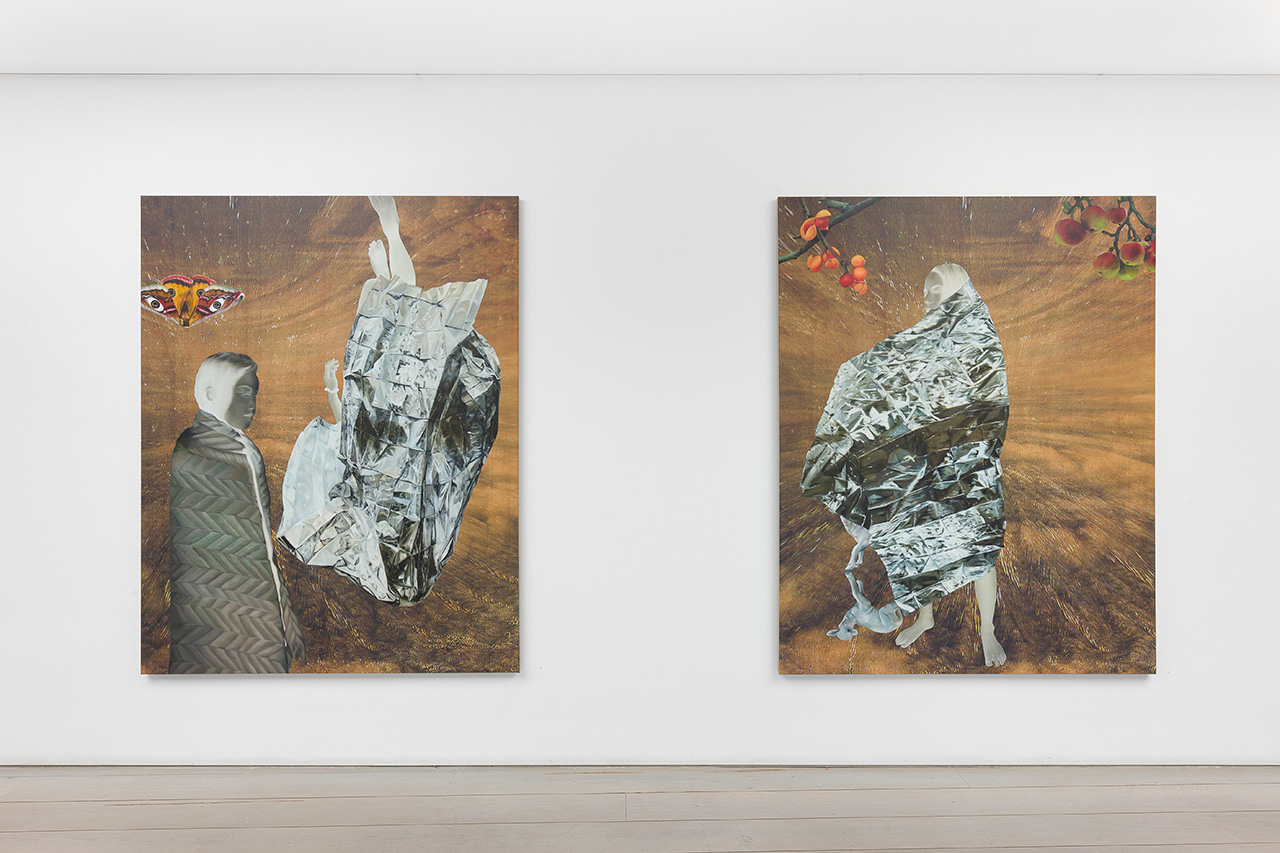

The artist also gives voice to the idea of transition in a series of three works that take the concept of shelter more literally. The Bridge to Innocence and Safety triptych features Young’s 16-year-old daughter painted in negative and ensconced in emergency Mylar blankets of the kind you would see in a disaster zone. They proved particularly challenging to paint, says Young, considering their appearance is entirely contingent on reflecting their surrounds. The artist’s daughter, who has also been painted in reverse, is surrounded by a litany of symbols that speak to a number of geopolitical and environmental crises, some borrowed and others conjured from an ongoing thematic concern with metamorphosis and duality: there are owl butterflies, a pair of porcelain deer made in the same factory that created Nazi memorabilia and a coral formation that doubles as a gesture to the work of Ai Wei Wei. These works have also been subject to an element of digital manipulation. Their backgrounds are distorted digital prints from the last landscape painting ever made by Giuseppe Castiglione, also known as Lang Shining, a Jesuit missionary who served as the court artist for three emperors in 18th century China and who found favour for creating a new style that combined traditional Chinese elements with his training in Western art.

Young’s earliest attempts at abstracting his own landscapes, witnessed in the inclusion of two large-scale works in the show, hewed too closely to their original images for his liking. A desire to bring what he calls “a physicality” to the image was satisfied by introducing “a figure” to the works – a curvaceous border where Young’s sheets of colour and flaxen linen meet at a precise but undulating juncture. There, at the razor sharp line where oil meets linen, pixel meets paint and one colour bleeds seamlessly into the next, you can come close to an experience that bridges the physical and digital worlds we straddle every day, but rarely find such harmony in doing so.

“And I’ve been doing it way before the iPhone billboards started doing it!” Young says, laughing.

This is a Shelter will exhibit at Olsen Gallery until June 24. More information is available here.

Tile and cover image: Courtesy of the artist/Olsen Gallery