News feed

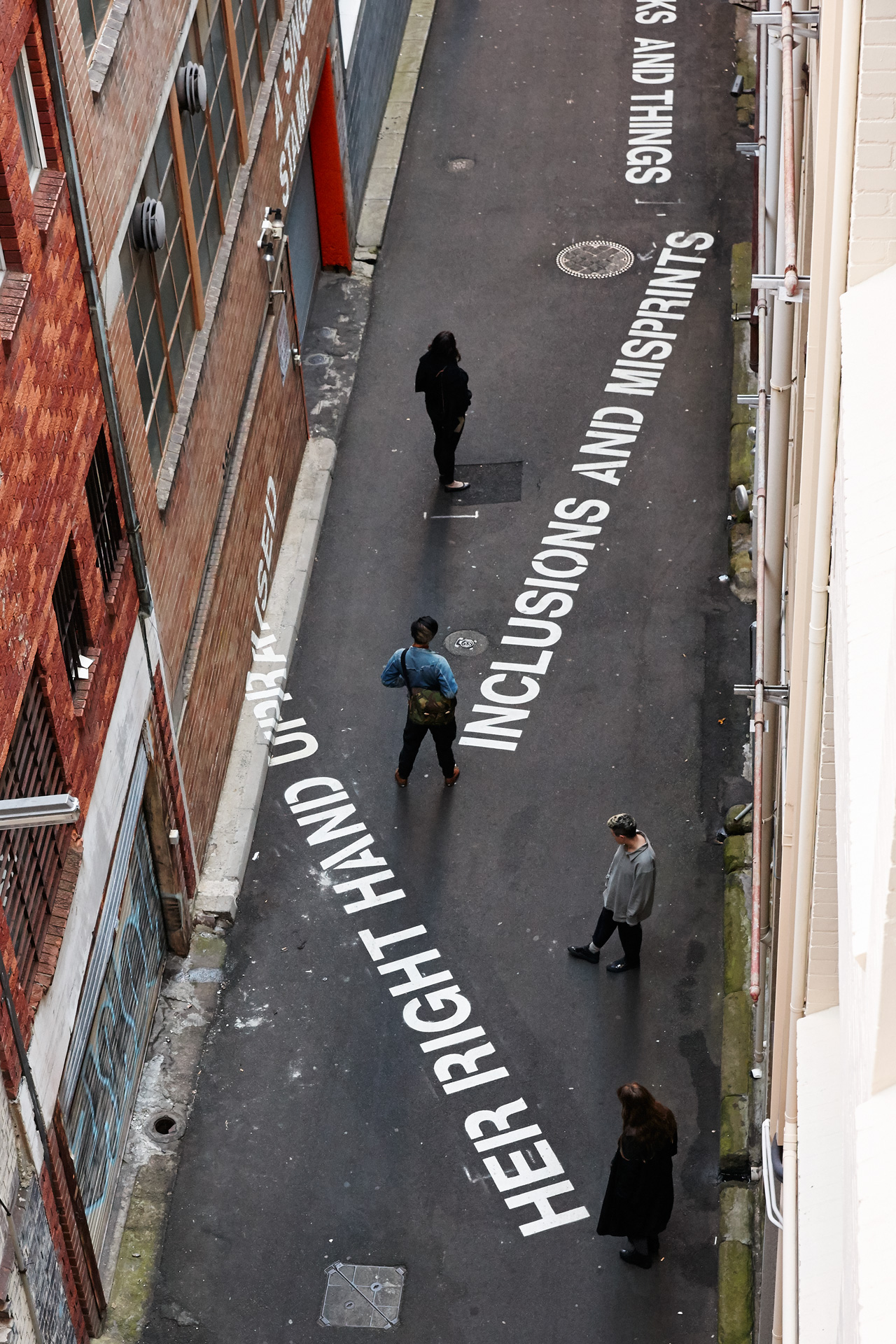

Agatha Gothe-Snape (pictured centre) with Brooke Stamp, Here, an Echo, 2015-16, Documentation of a scored walk from Speakers’ Corner in The Domain to Wemyss Lane, Surry Hills (26 June 2016) for the 20th Biennale of Sydney

Credit: Courtesy of the artist and The Commercial, Sydney/Rafaela Pandolfini

Even if you do not know Agatha Goethe-Snape by name, you will almost certainly by now have seen her face.

Or, at the very least, the likeness of it that comprised a great deal of the winning portrait of this year’s Archibald Prize. In the hands of her partner, the painter Mitch Cairns, Gothe-Snape – who is pictured artfully contorted yet graceful in repose, the planes of her face flattened with Matisse-like abstraction – has become a near ubiquitous presence across Sydney, adorning its bus shelters and festooning its lamp posts.

Her latest work, however, reverses that equation, because Here, an Echo, has Sydney all over it.

Here, an Echo was developed at the invitation of the 20th Biennale of Sydney and City of Sydney, who last year awarded the Sydney-born and raised Gothe-Snape with the second Biennale Legacy Artwork Project. Beginning in 2014, the City of Sydney has committed to commissioning a major work of public art from each of the three successive Biennale exhibitions. The Canadian artists Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller’s work City of Forking Paths, an app-assisted interactive augmented reality walk around The Rocks precinct, was the inaugural Legacy Artwork Project; Gothe-Snape’s Here, an Echo is the second of three commissions. As the first stage in the development of the work, an extended period of research which included performances, walks and conversations staged dozens on dozens of times throughout the duration of Biennale, resulted in the development of 14 singular phrases that from today now appear in perpetuity, writ large across the surfaces of an otherwise nondescript Surry Hills thoroughfare, Wemyss Lane.

“When invited to make the work, but [wanting] to respond to site, I asked myself the best way to really begin to get a feel for place,” Gothe-Snape tells GRAZIA. “Even though Sydney is where I live and grew up, it has so many stories, hidden histories and layers. We found walking a great way to try and tune into these – not to sound too hippy – but we wanted to use the body, how it moves through space, as a way to research. So walking with Brooke [Stamp, the choreographer], and others, was a really good way to glean a sense of place, and also a great way to meet people and engage with all types of people as audience. The walk became a kind of amorphous sculpture.”

Credit: Courtesy of the artist

Gothe-Snape and Stamp, who in the past have collaborated on a two-channel video installation and dance score, performed the first stage of the procedural project, the walk, over 60 times during the Biennale. The piece began at Speakers’ Corner in the Domain, before moving on toward Saint Mary’s Cathedral, the Moving Walkway beneath it, Cathedral Square and Hyde Park, before culminating at Wemyss Lane. Each iteration of the improvisational performance was invariably different, responding to the emotional, somatic and psychological conditions of its context, as well as those that preceded it. Gothe-Snape has described the work as “choreography for the city’ in the past; that first dance, in the intervening year, has seen the finished work evolve into something more closely resembling “an open ended two-way poem that you can read as you walk, or walk as you read!”

The process, the artist says, gave her a profound insight into how we use public artworks to deliver “very specific messages with very specific agendas. We learnt how to wait, to watch, to listen and dwell. We learnt about resistance and surrender.” It was also, of necessity, a work of endurance. “The combination of raising a toddler and birthing a major public artwork was a little demanding!

“I think we can imagine public art as more than monuments now, and also more than gimmicky decorations,” continues the artist, whose past public work commissions have included The Scheme was a Blueprint for Future Development Programs (imagine a life-size board game) at Monash University’s Caulfield Campus in Melbourne in 2015 and an interactive PowerPoint-based work for the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia’s National Centre for Creative Learning.

“For me, public art offers us an opportunity to make more space in public – space for imagination, open ended questions, ethical and moral ponderings and playful bodily relations. Opening up is what I am interested in. It is incredible I have been given this space for opening up. I also think public work should respond to its context and be shaped by its conditions into the world it will become part of.”

Agatha Gothe-Snape with Brooke Stamp, Here, an Echo, 2015-16, Documentation of a scored walk from Speakers’ Corner in The Domain to Wemyss Lane, Surry Hills (26 June 2016) for the 20th Biennale of Sydney

Credit: Courtesy of the artist and The Commercial/Rafaela Pandolfini

In the past, Gothe-Snape’s work has taken on many forms: improvised performances like Here, an Echo, are as much a feature of her work as slide shows, workshops, text-based works both found and invented, as well as more traditional art objects produced both by her hand and in collaboration with others. Even when working in bronze, steel or ink on paper, an element of performance is always within reach.

As part of the first three editions of The National: New Australian Art, a new biennial staged across three venues (the Art Gallery of NSW, Carriageworks and the Museum of Contemporary Art) Gothe-Snape is responsible for creating a six-year project that will appear at each of the three venues, The Fatal Sure/The National Doubt: a long-form documentary about Australian art. The first instalment of the work saw three large-scale text works quote directly from a monologue delivered by the art critic Robert Hughes at the conclusion of the series The Shock of the New, a televised documentary that aired in 1980 and explored the development of modern art from the 19th century onward. For the 2019 exhibition, Gothe-Snape will present a three-minute promotional trailer for the documentary. In 2021, the feature-length documentary will be presented in full.

“I think the main thing that characterizes my work is a willingness to be in ‘not knowing’,” says Gothe-Snape. “Often I think “it’s best to do as little as possible”, so once I have gone through my process, I take things away – it’s reductive – until there is just the little trace, or document, and this becomes the work. It is open to the viewers’ interpretation – like all art – but I hope has some sense of internal logic, so if you are willing to listen ‘BELOW THE LEVEL OF AUDIBILITY’ (another phrase in the laneway!) you will sense a certain gravity.”

Agatha Gothe-Snape, The Scheme was a Blueprint for Future Development Programs, 2014-2015, Monash University Public Art Commission, Monash University Museum of Art, Melbourne

Credit: Courtesy of the artist/Zan Wimberley

One of Gothe-Snape’s favourite public works is by the Turner Prize winning British artist Martin Creed. It is a neon sculpture, an installation commissioned to mark the transformation of the Tate Gallery of British Art into Tate Britain. It too features an equation, albeit one rendered in lower-case white neon letters: ‘the whole world + the work = the whole world’.

Work No. 232, as it is referred to using Creed’s non-linear numbering system, also underwent a similar change of medium from its first iteration as an ink and paper work before it found a second in life in public neon; both works from the two artists succeed in capturing in a pithy epigrammatic form the enormity and often the unknowability of a shared experience.

The 14 phrases that appear in Here, an Echo share a similar economy of language; while some are quotations overheard from onlookers to the choreographed performances, others draw on the history of Wemyss Lane and the present uses of the towering brick warehouses that frame it. Gothe-Snape’s favourite saying is also, perhaps, the weirdest: “‘PLANTS AND BIRDS AND ROCKS AND THINGS’, strangely enough [is] a quote from the classic hit Horse with No Name by America, which somehow made its way into our consciousness during our process,” says the artist. “We even got a choir to sing a version in the moving walkway! Even though this phrase imagines a place as its contents, I think it is actually referring to the rich ambience and spirit of site. It is also positioned here so it subtitles the rows of bins that so often edge the laneway.”

Credit: Courtesy of the artist

The spirit of the site is part of the reason for Gothe-Snape choosing it over Surry Hills’ myriad other laneways.

“Once a humming, bustling, crowded residential strip – some call the first Chinatown – was resumed by the local government in 1913 to make way for industry and enterprise,” she says. “All these layers of history, and of course imagining the land pre-colonisation, imagining the lie of the land, its qualities, drew me to it.” Then there are the topographic realities of the site, its gentle incline and the sheer length of the street somehow manage to remain hidden from the din of the world around the corner.

“I loved that it can be viewed from the terrace at the rear of 1 Oxford – almost like a dress circle, so the walkers become dancers for the smokers!” Gothe-Snape hopes that, on inadvertently stumbling across the work, other passersby will assume the role of the dancer, “making their own meaning as they stumble, dance, and wander in the spaces between the words.”

Tile and cover image: Courtesy of the artist